When The Shift learnt that Adrian Hillman was not among the 11 individuals, including former Chief of Staff Keith Schembri, who were arraigned and charged with a series of financial crimes, it sent questions to the police about his whereabouts.

The Shift’s questions remained unanswered, but it was not long before it transpired that he is currently residing abroad and that Maltese authorities have sent a request for the extradition of Hillman to their counterparts in the UK.

The Maltese authorities point out that the process could be a long one. Understandably – not least because in Hillman’s case the “requested State” is no longer part of the European Union and has only recently agreed to comprehensive provisions related to the surrender of individuals between it and the EU.

Before Brexit

Up until the UK’s fraught departure from the bloc, both Malta and the UK applied the procedures popularly known as the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) – a framework that was designed to make it easier for an EU State to transfer people to either face prosecution or serve a prison sentence in another EU Member State.

Based on the Framework Decision on EAW, and enacted in 2004, the process was designed to simplify and expedite extradition procedures through strict time limits and removing what is known as the “double criminality check” for 32 categories of offences. This means that authorities in the requested State do not need to use up time and resources to check whether an act is a crime in both countries.

It also strengthened oversight and human rights protections and did away with political involvement, since it was the designated judicial authorities that decided whether someone extradition should be sought (by the requesting State) and granted (by the requested State). The procedure also limited the grounds on which the surrender of an individual could be refused.

Every country party to the EAW system has what is known as a SIRENE Bureau (Supplementary Information Request at the National Entry). This is a group of personnel who receive and respond to alerts given from other Schengen Member States. Malta has its own SIRENE bureau and in the UK, this is the National Crime Agency (NCA).

The NCA acts as a legal gateway between those authorities requesting an arrest and those carrying it out. They also assess the proportionality and legal validity of EAW requests into and out of the UK. If a EAW is not considered valid, it is returned to the requesting country, if it is valid then the extradition is decided by a court.

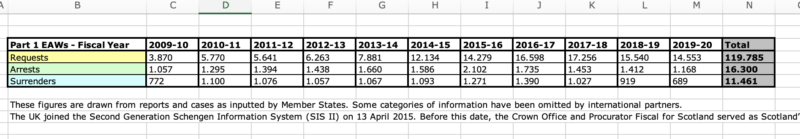

And even with this seamless procedure in place, the number of surrenders from the UK are noteworthy. According to the National Crime Agency, for the year 2019-2020, the UK received a total number of 14,553 EAW requests from 27 EU countries. Out of all these requests, 1,168 resulted in arrests – but only 689 resulted in actual surrenders.

A summary of the data related to European Arrest Warrants requests from 27 EU countries to the UK. Source: The National Crime Agency (NCA)

These numbers clearly need to be interpreted with caution. To begin with, if a country doesn’t know where their wanted person is, they may issue EAW to multiple countries including the UK. Also, the request, arrest and surrender figures might not always be related to the same group of people in the same year, given that processes and timescales may have overlapped. Still, the number of surrenders remains small.

After Brexit

The new UK-EU surrender arrangements for extraditions between the UK and the EU forms part of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (Title VII of Part 3 of the agreement) that was signed on the 24 December 2020, mere days before the end of the transition period that would usher the UK’s official departure from the European Union.

Many of the provisions in the new surrender arrangements are similar to those provided by the Framework Decision on the EAW but there are some notable differences. The first is that the European Court of Justice no longer has jurisdiction over the new surrender arrangements. These will now be overseen by a ‘Specialised Committee on Law Enforcement and Judicial Cooperation’.

Another significant change is that the new arrangements are subject to the principle of proportionality. What this means is that during an extradition hearing, the Judge must decide whether extradition would be disproportionate or incompatible with the requested person’s rights. None of these new elements should be cause for concern in connection with the purported request for the arrest and extradition of Hillman. So, what happens next?

The process

The procedure now in place between Malta and the UK will follow these steps: After the NCA applies a proportionality test to the extradition request, a certificate is issued, and the requested person is arrested and must be brought before a District Judge for an initial hearing.

During this hearing, the Judge must confirm the identity of the requested person, inform the person about the procedures for consenting to his or her extradition and fix a date for the extradition hearing if the requested person does not consent to his or her extradition.

The extradition hearing should then begin 21 days following the person’s arrest. During the extradition hearing, the Judge must be satisfied that the conduct described in the warrant amounts to an extradition offence (in most cases that it would also be considered a crime in the UK) and that none of the statutory bars to extradition apply.

The Judge must also decide if extradition would be disproportionate or would be incompatible with the requested person’s human rights, but if the Judge decides it would be both proportionate and compatible, extradition must be ordered.

However, should the requested person or the requested State be unhappy with the Judge’s decision, they may ask the High Court for permission to appeal the decision. If the High Court grants permission, it will go on to consider the appeal.

As things stand, the ball is now very much in the UK’s court (with a small “c”), and there could be issues or points that Adrian Hillman may decide to challenge. This would lengthen the procedure considerably.

Malta may have come a long way since the day that by a simple exchange of letters Malta inherited from the UK a raft of extradition treaties, but still, today extradition from the UK is no piece of cake.

Thanks for a very insightful article,obviously well researched and to the point.

Would it not be ironic if Mr Hillman were to fight extradition on the basis that he has no chance of a free trial in a country riddled with corruption, bribery, and a judicial system compromised by political interference.

I have no legal training, but I can see this sort of defence coming to the fore at his hearings.

Agreed, Iain M – and there’ll be many UK “human rights” lawyers fighting each other to represent him.