Joseph Muscat has decided to ignore calls by a delegation of MEPs chaired by Socialist MEP Ana Gomes to sack Konrad Mizzi and chief of staff Keith Schembri arguing that the delegation had already made their mind before even landing in Malta. But can Joseph Muscat afford a stand off with MEPs at a critical juncture where all eyes are on Malta?

In a sign that Muscat is now facing pressure within his own political family, Gomes – who chaired the delegation of MEPs which prepared the report – called on her fellow Socialist MEPs not to act in the same way the European People’s Party group has been acting regarding Hungarian Prime Minister Órban, “protecting him because he is from the family”.

The comment was interpreted by influential EU journal Politico as a “move by some fellow Socialist MEPs to say it’s time for Prime Minister Joseph Muscat to resign”.

Surely as one of the last surviving Socialist leaders in Europe, Muscat is bound to continue enjoying clout in his own political family but individual MEPs like Gomes may feel more confident in distancing themselves from what they perceive as an embarrassment.

This opens a new chapter in Muscat’s love affair with Europe which blossomed during his spell as an MEP between 2004 and 2008. His identification with the European Socialists was so strong that his own bid for the Labour leadership carried the weight of an endorsement of Martin Schulz, then chairman of the Party of European Socialists.

Muscat is now in the difficult position of having to choose between the respect he craves for on the international stage and defending his own clan in Malta.

Since his election in 2013 Joseph Muscat walked on a tightrope between actively seeking respectability in Europe, while pursuing a number of policies which distanced him from his own Socialist family.

The first visible rift was his call on Europe to wake up and smell the coffee on migration by threatening a push back of migrants a few months after taking office in 2013. But Muscat quickly reversed this position and successfully pursued a policy of cooperation with Italy which spared Malta the entry of more boats in the following years.

He found himself at odds with the European Socialists on the sale of citizenship decreed by then Socialist group president Hannes Swoboda as one undermining European values. But after a showdown with the European Parliament, Muscat reached an understanding with the European Commission based on a vague residency requirement of one year.

Unlike the right-wing pariahs running Poland and Hungary, Muscat scored points in progressive quarters by putting Malta in the lead on gay rights. Muscat also projected himself as a role model for an embattled centre-left in Europe. In an interview with the Economist he was described something of a rarity in the EU: “a relatively successful |Social Democrat”.

Unlike his predecessors, namely Dom Mintoff and Alfred Sant, Muscat actively seeks international legitimacy to the extent that even in the last general election he brought over former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair and former Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi to address Labour meetings.

His commitment to resign after 10 years in office and the importance he gave to Malta’s EU Presidency term fueled speculation that Muscat was after a post in Brussels, particularly that of President of the EU Council, a post currently occupied by Poland’s Donald Tusk.

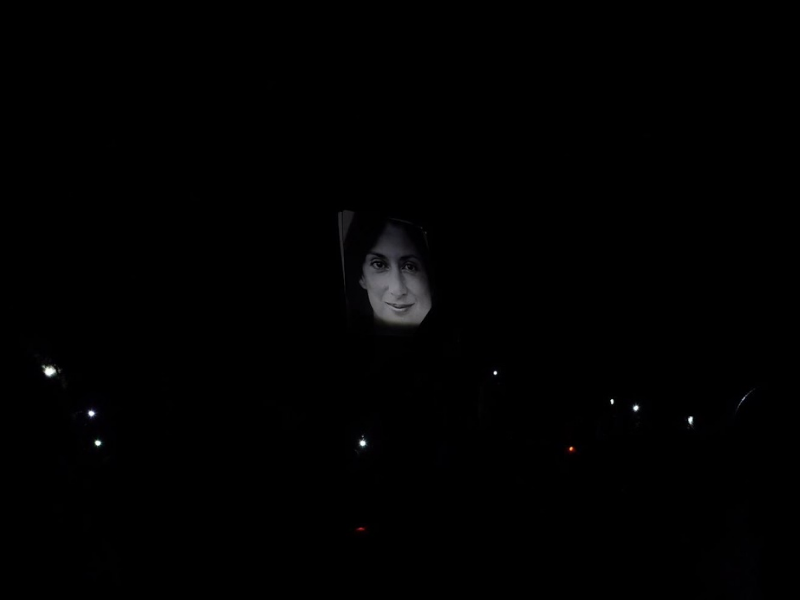

Inevitably the murder of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia turned the international spotlight on Malta, bringing more attention on Muscat’s lack of action after Panamagate and previous controversies like the cash-for-passports scheme.

BBC journalist James Sweeny described Muscat as “Europe’s Artful Dodger” while Italian anti-mafia expert Roberto Saviano described Malta as a “center for corruption.”

But it is doubtful whether this will in any way dent Muscat’s national ratings.

Muscat can also bank on the European Parliament’s limited clout. What counts most in Europe are the bilateral relationships between Prime Ministers and the relationship between member states and the EU commission.

European Commission president Jean Claude Juncker’s omission of any reference to Panama when addressing the Maltese Parliament last year was emblematic of the state of affairs.

Criticism abroad rarely erodes trust in strongmen politicians. Despite coming under heavy criticism from its political opponents for undermining democracy and the rule of law, the popularity of Poland’s Law and Justice government remains at record levels.

Closer to home, former Italian premier Silvio Berlusoni, who devised laws to protect himself from being prosecuted while in office, is now on the verge of leading his party back to government.

While international rebuke may have dashed Muscat’s retirement plan, Muscat’s final reckoning will be that with the Maltese electorate. Ironically rather than forcing Muscat to exit the political scene, recent events may well end pushing Muscat to reconsider his decision not to lead his party into a third general election.

Yet, the major risk he faces is that growing international scrutiny could well have an impact on the country’s economic performance, something which could sink his popularity at home.