The present government clearly has an electoral mandate to convene a convention to reform the constitution. The PN also made the same promise in its electoral manifesto. But beyond this joint commitment, both parties seem heading towards unchartered waters.

An analysis of electoral commitments shows that neither of the two big parties have come with a clear blueprint which binds them on how to proceed in these discussions.

Neither have they proposed how the members of the convention will be chosen. Will political parties seek to dominate the process by inserting proxies in the convention or will they take a back seat?

A role model for Malta could be Iceland a small island state like Malta where the constitutional debate was crowd-sourced and delegated to a democratically elected but non partisan assembly. The text of the new constitution was approved by 67% in a referendum held in 2012. But final approval by parliament was still required and never granted.

It is difficult to envision a similar thing happening in highly partisan Malta where even student council elections are monopolised by proxies of both major parties. So where do the parties stand on constitutional reform?

A constitution born out of an institutional crisis?

Of the two represented in parliament it only the PN which made concrete proposals with regards to the appointment of the highest offices of the state, including the President of the Republic and the police commissioner. The PN proposed that these are only appointed after securing a two thirds majority in the first vote and a simple majority in a third vote if consensus is not reached.

The most tangible proposal in the PL’s electoral manifesto is the creation of a constitutional mechanism through which errant MPs and public officials can be removed from office, a mechanism which may have saved the country much trouble had this reform been in place at the time of the Panama revelations.

But the PL’s manifesto praises the strength of the country’s institutions and argues that our constitution already “guarantees checks and balances necessary to safeguard the interests of the people and for the country to function as a modern democracy”. It is in this context that Labour reiterates its commitment to “strengthen the institutions”.

Does this suggest unwillingness to introduce more constitutional checks and balances? And if increasing checks and balances is not the PL’s primary motivation for amending the constitution, what is the point of calling for a second republic-a phrase used in countries which have passed through a veritable revolution like tangentopoli in Italy and the Algier crisis in 1958 in France?

A second republic?

This raises the question on whether is it justified to talk of a second republic when our country has neither been through war, revolution or a judicial wipe-out of its political class – epochal events – to signify the passage from one republic to the next? Why give much-needed and long delayed reforms in our democratic structures the semblance of an epochal earthquake?

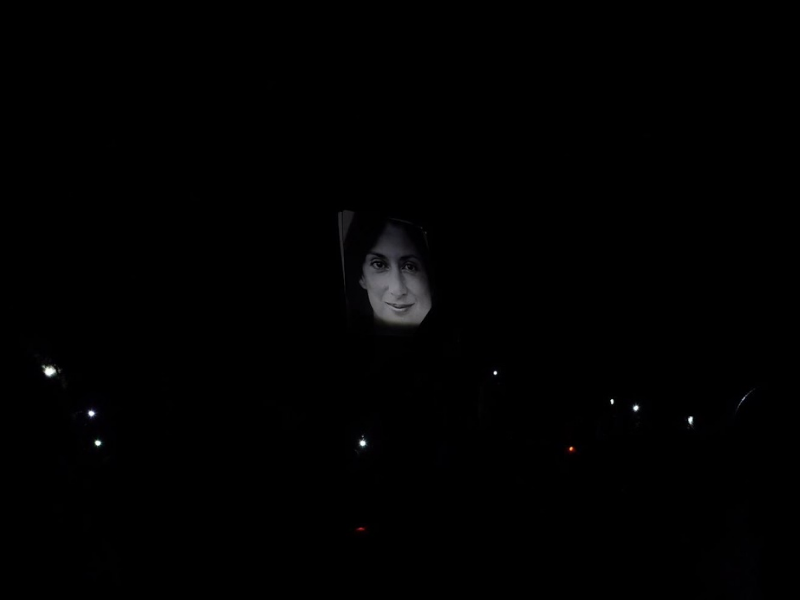

Perhaps Caruana Galizia’s assassination was the jolt which awakened interest in the need to strengthen the country’s institutions. In fact civil society has rallied behind calls for the replacement of the police commissioner and the attorney general by more consensual figures enjoying the trust of two thirds of the house of parliament, a demand out-rightly rejected by government.

On his part the Prime Minister immediately deflected criticism on the rule of law by resurrecting its proposal to convene the constitutional convention.

But can civil society trust the government rebuked by the European Parliament for not upholding the rule of law with the task of reforming the constitution?

History is full of examples of constitutional reforms being used by governments to centralise power .

In France the establishment of a fifth republic saw the consolidation of the office of the President personified at the time by war hero Charles De Gaulle, turning the country from a parliamentary democracy like Malta to a semi presidential one. In a more sinister development Turkey has also seen a referendum which strengthened the position of an elected Presidency in a more authoritarian direction. Will Muscat move to take steps which limit the power of the party in government or to further centralise power in Castille? And will both government and opposition be keen on accepting a reform of the electoral system which limits the power of both?

Referendum before or after parliament’s approval?

Moreover speaking in parliament last month Muscat hinted at approving constitutional change through a referendum if the proposals included in the changes are not included in his party’s electoral programme.

He even suggested that the referendum would be held on the day of the next general election…a decision which could further polarise the debate. The risk is that the debate on reforms will be obscured by the political bickering which normally dominates Maltese elections.

The PN leader has proposed a shorter time-frame proposing approval by referendum in next year’s elections for the European parliament.

One major question is whether this referendum will compliment a previous two thirds majority in parliament or whether it will take place before a final vote in parliament. Will the referendum ratify a consensus already reached in parliament or will it be used to force MPs to respect the popular will? If the latter was the case approval by say 55% of the electorate would be used as moral pressure on MPs to secure the necessary two thirds majority in parliament.

Since the constitution sets the rules for our democracy, changing it in the absence of a wide consensus would be dangerous. The Icelandic model did provide a number of guarantees to avoid any majoritarian solution.

The Icelandic model

In response to the collapse of banks in 2009 thousand of Icelanders took to the streets demanding constitutional change. The uproar led to the passage of a parliamentary statute to guide the process.

Next was the convening of a randomly drawn group of 950 citizens to generate ideas for constitutional reform. Then, in the fall of 2010, twenty-five ordinary Icelanders were elected from a field of over 500 to serve on a constitutional council that would formulate a new constitution. The councilors sought wide participation, and Icelanders were able to follow the council’s decisions and contribute suggestions through the internet using a Facebook page.

There was an iterated process of drafts and comments, which led to some changes in the proposed draft. The final draft produced by the commission greatly expanded direct democracy, allowing the public to be involved in ongoing governance.

The draft also decreed the country’s natural resources to be the property of the state. This provision sought to effectively reverse the country’s privatization of fishing licenses in the early 1990s. The draft was approved by a two thirds majority in a consultative referendum in October 2012. But the reform failed to pass the two next hurdles approval by parliaments in two successive legislatures.