Consider these two extraordinary cases. A minister does the right thing and terminates a corrupt contract; but when journalists ask why she did it, she purses her lips as though saying anything would embarrass her government. Justifying justice seems uncomfortable.

Then there’s the minister who the courts find to have directly, and repeatedly, broken protestors’ right to freedom of expression; but he takes credit for this, saying that since the courts found him guilty, his government is innocent of interfering with the independence of the judiciary. Being condemned is a triumph that proves all those carping critics wrong.

Does any of this make sense? Well, no and yes.

When Julia Farrugia Portelli terminated Konrad Mizzi’s contract, she did what everyone wanted her to do. It makes no sense that she shies away from setting out the principles behind it: no revolving doors for retired ministers, and certainly not for disgraced ministers.

And of course Owen Bonnici makes no sense. He’s just gabbling away.

However, in both cases the lack of sense is understandable. This is what a government looks like when it has lost control of the message.

Farrugia Portelli cannot say a single word against Mizzi without opening a can of worms – about why her colleagues put up with him; about Joseph Muscat, who approved the rotten contract.

It’s why the Prime Minister has put up the charade of saying he has not asked who approved the contract. He doesn’t have to. We all know who did. But the moment Robert Abela says he knows, then he’s made himself vulnerable to questions about why he’s not taking action against Muscat, now one of his backbenchers.

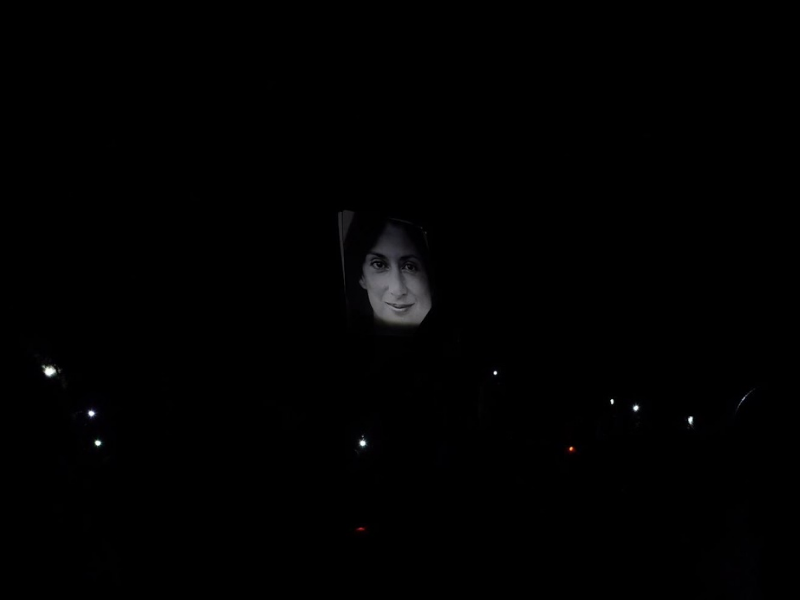

As for Bonnici, he spouts shiny distracting nonsense because the full truth is more embarrassing than the court judgement. The monument was cleared to avoid vandalism and violence by Labour supporters, who for years were incited against Daphne Caruana Galizia by the Party media and social media machine.

That doesn’t justify trampling over the rights of freedom of expression. But you can understand why Bonnici feels he’s carrying the can for policies cooked up and pursued by others. Abela understands this. If Bonnici is sacked, Muscat’s leadership gets implicated. The can would be opened and the worms wriggle out.

For years, Labour thrived on its message of “prosperity with a purpose”. It lived off its shows of unity, believing that circling its wagons, around a minister under fire, was a show of strength. Both the slogan and the strength are now in question.

Circling the wagons turns out to have benefitted Muscat’s close friends but it didn’t strengthen Labour. It simply spread the guilt to Cabinet as a whole, as well as to certain ministers individually. It tainted ministers who, under different leadership, would have enjoyed the reputation of making a creditable contribution to public life.

Strengthening Muscat weakened Labour. It has been rendered vulnerable. People are querying whether the “purpose” of prosperity was sinister. Public discourse has shifted from Labour’s chosen battleground to good governance, the battle horse of the PN in 2017.

It’s not just ordinary people. It’s the economic associations themselves – the Chamber of Commerce, the Chamber of SMEs – who are insisting on raising governance policy matters.

Meanwhile, when Labour does take action on good governance, it has to be careful not to let the achievement have unintended consequences. When you’re afraid that a good action might spiral out of control, that’s a sure sign you’re on the back foot.

None of this means that Labour can’t recover its former confidence. For one thing, people are ready to give Abela some room to wobble. They see through the weak excuses but are willing to put up with them – if the larger issues get fixed in the end.

Second, Labour is not alone. Even if Labour stumbles, what matters is whether the PN continues to slide back further.

Paradoxically, one of the victims of Labour’s current wobble is likely to be Adrian Delia. For the fact that Labour seems on the back foot will increase opposition supporters’ anger with Delia, whom they consider to be ill-placed to take advantage of Labour’s vulnerability.

Such a development will disguise Labour’s problem. But remember, the problem is not just about rhetorical coherence. It’s about taking action to keep the lid on the can of worms, not letting the worms climb up the sleeves of serving ministers.