He had it in his grasp, only to fall from grace. He didn’t overreach. He wasn’t overlooked. It wasn’t a near miss. He was blackballed.

It didn’t happen because of anything Hungary or Poland wanted about matters that had nothing to do with him. It had everything to do with him and it was western Europe that flunked him.

That is the nub of this website’s report on the true story behind why Joseph Muscat didn’t get one of the top EU jobs allocated last week. It contradicts both Labour spin and the critics snickering at it.

The spin tells a familiar story straight out of the Eurovision playbook from back in the glory days when Malta had good chances of reaching the top three.

Here’s how it goes. Our talented singer, with the entire country behind her (or him), gives a great performance on the European stage. It deserves to be rewarded and it’s so close right up till the end. But then block-voting by the eastern and former Soviet countries does us in.

Never mind, the singer is still given a hero’s welcome in Malta, which is lucky to be able to hear so much more of the national nightingale.

The EU job saga is being spun as the Eurovision narrative of the near-miss

Then there’s the counter-narrative led by the local Terry Wogans and Graham Nortons, the people who live to scoff at the song, the dress, Joseph Chetcuti’s violin and, not least, the very ambition, the idea that the contest could have been won in the first place.

The EU job saga is being spun as the Eurovision narrative of the near-miss. Karl Stagno Navarra and Kurt Farrugia play Charles and Ron, Labour activists play the crowds at the airport, and PBS plays, well, itself.

But the critics are playing this game too when they acerbically point out that there’s no mention of Muscat in the international press. Their narrative is that of overreach, that Muscat tried to punch above his weight and failed.

Somewhere in the bowels of cyberspace, in the belly of Facebook, the esophagus of Twitter or the colon of Instagram, a wit must surely already have compared Muscat’s ambition and the hymns of his acolytes to one of Malta’s Eurovision songs: Chameleon, perhaps, or Seventh Wonder, or, cruelly, Desire.

This narrative prides itself on its mockery but it actually pulls its punches. Overreach means you’ve remained where you are. Your status hasn’t changed. You haven’t lost any prestige, even if you haven’t gained any, either.

The Shift’s report punctures both stories. Against Muscat’s critics, it reports that Muscat was indeed at one point assured of becoming the next President of the European Council. Against Labour’s spin, it shows that Muscat blew it.

The report is based on what informed sources were saying this week. But it’s a story a long time coming. Last year, The Guardian carried a report called, ‘How Joseph Muscat’s Glittering Political Career Lost Its Lustre’. Its story was that Muscat’s reputation was (already then) in tatters.

Did Muscat botch it because he mishandled these affairs? Or could he not handle them another way?

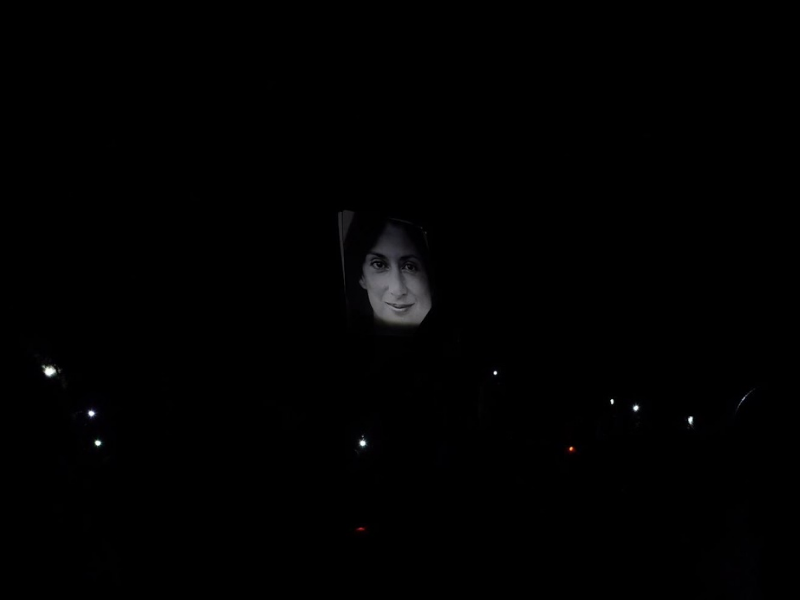

The report was part of the Daphne Project. Muscat’s stock had gone down for reasons that are now familiar. They’re all listed in the recent resolution of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe: Muscat’s handling of the Panama Papers, Pilatus Bank, passport sales, and the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Here is the interesting question. Did Muscat botch it because he mishandled these affairs? Or could he not handle them another way?

The first question suggests his fault was misjudgment. The second points to a deeper cause: a modus operandi he cannot change. He’s a leopard unable to change his spots, however much he’d like to be a chameleon.

His modus operandi won him power in Malta but lost him his reputation in Europe. Will it stop there – with frustrated ambition? Or will European pressure begin to erode his power here, too?

This second possibility raises the spectre of a wider problem for Labour itself.

Muscat is the Panama Gang’s second victim. The first was Konrad Mizzi, forced to resign ignominiously from his position as Labour Deputy Leader after only a few weeks (he doesn’t even mention this role on his Wiki page). Now he’s seen widely as a liability within Labour itself. He must scrabble to guarantee himself a political future in a post-Muscat scenario.

Muscat’s position within Labour is secure. But for how long is less certain. It all depends on how serious the Council of Europe gets about demanding an end to the impunity of Mizzi and Keith Schembri.

If the pressure continues, it may be the entire government that begins to pay the price. If Muscat does not relent, he may well find that the question of succession begins to be raised again. Not loudly, but in whispers.

Still, whispers can turn to murmurs. It might turn out that his loss of a top job was not the end of a road but the beginning of a new one.

ranierfsadni@europe.com