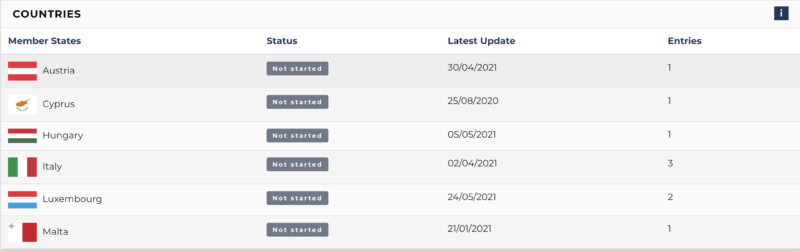

Malta is one of six European countries that have made zero progress and haven’t even started transposing the EU Directive on whistleblowing that came into force over two years ago, according to the EU Whistleblowing Monitor launched this week.

The Directive aims to protect people who report breaches in European law and afford protection to whistleblowers. It must be transposed into national law by no later than 17 December 2021.

📣WIN is delighted to announce the launch of the:

🇪🇺EU Whistleblowing Monitor🇪🇺

A new online platform to monitor the transposition of the EU Directive on #Whistleblowing made in collaboration with @TI_EU & @EUROCADRES

➡https://t.co/rpsZ4nimw2 pic.twitter.com/R0kBdqinmO

— WIN (@whistleblowing) June 3, 2021

The Monitor was set up by the Whistleblowing International Network (WIN) to track the progress of all member states in fulfilling their legal obligations. WIN was set up to strengthen the capacity of civil society and to protect public interest whistleblowers around the world. They also aim to support the efforts of civil society in turning legal rights into active protection for whistleblowers.

Since the Directive entered into force in 2019, most EU member states have got to work in transposing the various provisions into their own domestic legal systems.

Sadly, Malta is not among them. According to the Monitor, the only update from the Maltese authorities in relation to the Directive is the justice minister saying it will require amendments to the current whistleblowing legislation. The statement was accompanied by comments that an office called “strategy support” will be tasked with coordinating efforts.

That update was given in January and no progress has been made since.

Other countries that have also failed to start the process include Hungary, a country that has been a significant cause of concern in recent years due to corruption, the erosion of the rule of law, declining media freedom, rising right-wing rhetoric, and increasing state capture.

Cyprus is another country that is marked as “not started” on the platform. There was some talk in parliament about it in April 2020, but there are no further developments. In terms of corruption, the country ranks lower than Malta according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. Reporters Without Borders notes the media is often plagued with threats and intimidation from politicians, police, and the Orthodox Church.

Luxembourg is also listed as “not started” but an update from 21 May states that a draft proposal will be announced imminently. In Austria, where the process has also remained stagnant, Transparency International Austria is campaigning for the government to implement the Directive as well as additional recommendations.

Malta’s history of protecting whistleblowers is non-existent. While there is a Whistleblower Act which on paper prohibits the whistleblower from being subjected to detrimental action, it’s advised they report the matter first internally, before the authorities.

This results in a situation whereby the whistleblower is potentially reporting wrongdoing to the very people involved in it.

Furthermore, in recent years, two whistleblowers involved in some of the country’s most high profile cases have been refused the status.

Jonathan Ferris, a former FIAU official who claims to have evidence of corruption at the highest levels of government was denied protection under the Whistleblower Act. The argument was that he should have first revealed what he knew to those he was accusing of wrongdoing. Not only did Ferris lose his job at the FIAU but the wrongdoing he reported was never investigated.

The government also denied whistleblower status to Maria Efimova who revealed information on Pilatus Bank and Egrant company. She fled from Malta due to fears for her safety but was arrested in Greece after Malta requested her extradition. Eventually, the Greek courts refused the extradition order.

Despite Malta’s lack of progress, the country pledged to protect whistleblowers at the UN this week. Signing an 87-point declaration on ending corruption, protecting journalists and ensuring justice for corrupt officials, the government also promised to create a safe environment for those exposing wrongdoing.

Point 30 reads: “We will provide a safe and enabling environment to those who expose, report and fight corruption and, as appropriate, for their relatives and other persons close to them, and will support and protect against any unjustified treatment any person who identifies, detects, or reports, in good faith and on reasonable grounds, corruption, and related offences.”

It adds that they will criminalise the obstruction of justice, protect victims, witnesses, and justice and law enforcement officials from relations, threats, intimidation, or physical violence because of their revelations.

Malta has less than six months to go to transpose the Directive into national law, two months of which parliament will be closed. Time is running out if the government wants to remain in line with its international legal obligations for protecting whistleblowers from harassment, threats and legal abuse.

The whistle blower that never whistles this exactly our law.