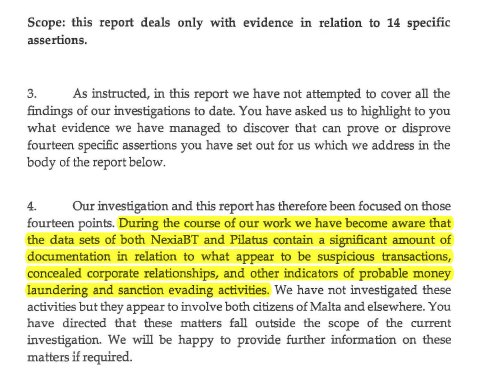

Now we know why Joseph Muscat held back publication of the full Egrant findings. It was to protect his former chief of staff Keith Schembri, his ‘star’ Minister Konrad Mizzi, Nexia BT partners Brian Tonna and Karl Cini and even Pilatus Bank and its owner Ali Sadr Hashemi Nejad.

What we still don’t know is who owns Egrant. The magistrate and his experts, it transpired, went through great pain to explain that it (and many other things) were not in scope. And Muscat and his cronies did their best for us not to find out.

When Muscat announced the publication of the conclusions of the inquiry, he did not tell the public that the documents being published were in fact only part of the conclusions. The Shift did.

What they chose to leave out, another 26 pages, was the part (conveniently titled ‘Other Conclusions’) that includes the actual recommendations made by the Magistrate where he orders the police to take action.

Muscat did not want us to know that.

The magistrate ordered the police to investigate Cini, partner of Tonna in Nexia BT, the company that set up these secret offshore structures for the top brass in our government to stash away the spoils of war – a war they waged against their own people.

It must be stressed: the Magistrate ordered the police to investigate Nexia BT’s Cini.

But the Police Commissioner just sat there, while Muscat hid behind ‘advice’ of the Attorney General not to publish the report.

The people Muscat was protecting were those closest to him, while the government deployed a taxpayer-funded propaganda blitz to sell the country a lie.

The point of an inquiry is to collect and preserve evidence. Its conclusions are not judgments on innocence or guilt. The findings and recommendations are for the police to act on and the Attorney General to litigate. What was the point of this inquiry if nobody was going to do anything with the evidence?

It is fair to argue that the inquiry was in fact unnecessary. Muscat could have turned to Cini and Tonna and asked them who owns Egrant, if he really did not know.

He could have asked them at least as early as 2016 when the name was first revealed by the late Daphne Caruana Galizia, assassinated in October the following year.

We are not expected to believe that Muscat and his team did not ask that question because they had a sudden inclination to respect boundaries. No, they spoke of ‘the best of times’ and ‘Blockchain Island’ while they got an inquiry they planned to twist and use only to their own advantage.

And that is exactly what they did. They had it all planned out.

Apart from Cini, the Magistrate ordered the police to investigate Pilatus Bank’s operations for money laundering and Egrant whistleblower Maria Efimova. We heard zilch about the first two, but they hunted Efimova with an international arrest warrant. She won the case against extradition in a Greek court.

A few hours after the late journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia reported that Egrant belonged to Michelle Muscat, the chairman and owner of Pilatus Bank was caught on camera exiting the building with bags suspected to contain documents critical to the investigation and boarding a plane soon after. Photo: Net News

Then they launched an extensive and expensive two-pronged campaign: to whitewash their reputation and discredit anyone who demanded to know who owned Egrant. That included a dead journalist, assassinated by those in power.

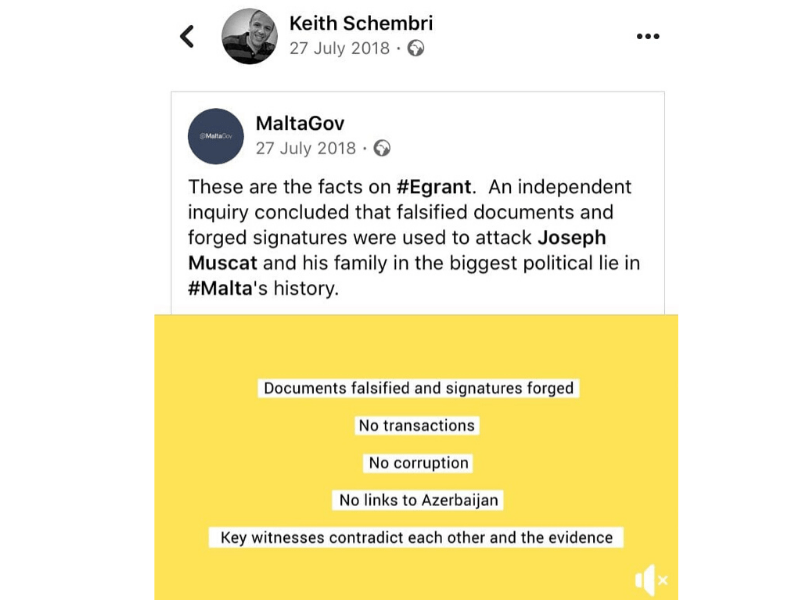

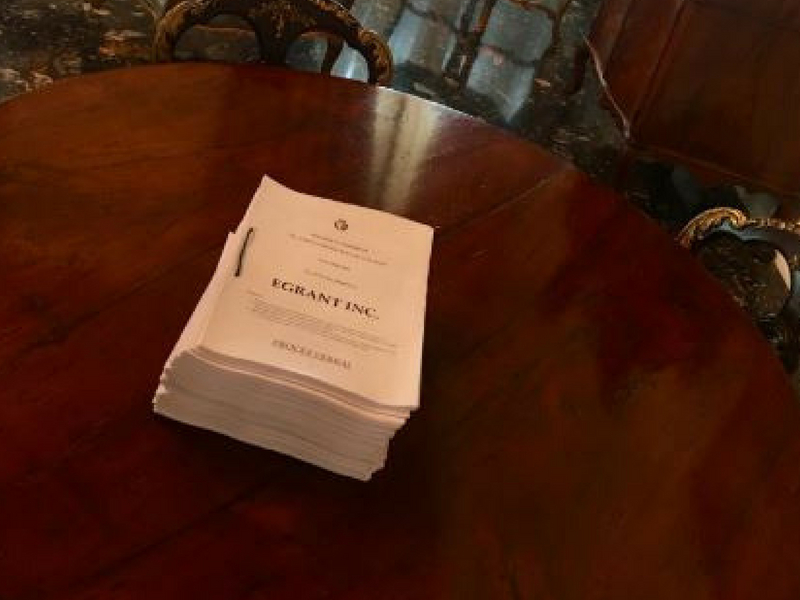

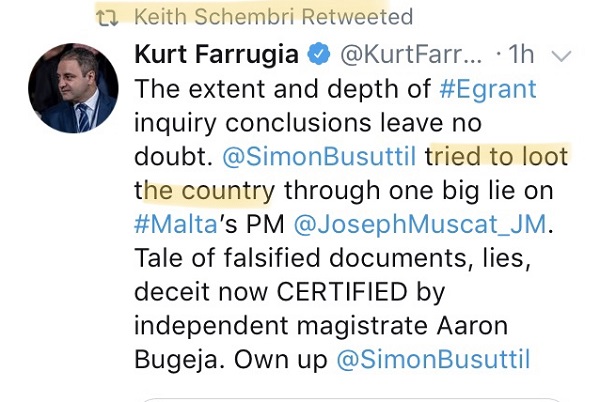

The former Government Head of Communications, Kurt Farrugia, recently installed in a new job at Malta Enterprise with compensation of over €100,000 if he is fired or resigns, had immediately posted a photo on Twitter of the full report on a desk at the Prime Minister’s Office.

He also immediately embarked on a list of accusations nobody could contest because they did not have access to the document.

The full Egrant inquiry shown on Twitter by Prime Minister’s former Head of Communications Kurt Farrugia.

He spoke of “falsified documents,” (now attributed to Cini of Nexia BT) and then went on to say that the “deceit [was] now certified” by a Magistrate. In reality, such an inquiry does not certify anything but collects evidence and testimonies that are put forward for further investigation that was never done.

“The extent and depth of the Egrant inquiry conclusions leave no doubt Simon Busuttil tried to loot the country with one big lie on Malta’s Prime Minister. Tale of falsified documents, lies, deceit now CERTIFIED by independent magistrate Aaron Bugeja,” Farrugia said as he was posting photos of the full report as though the sight of a voluminous document proved him right.

The full conclusions now published tell a different story. Muscat’s refusal to publish allowed the inquiry to be weaponised amid much fanfare, spin and a tear or two.

Now, the question is: If the Egrant report could get this far 18 months ago, why are the other inquiries dealing with evidence related to those involved in Egrant findings, namely Schembri, Mizzi, Tonna, Cini and Adrian Hillman not yet concluded?

Is that due to an overload of work, a lack of resources, or pressure applied by those who think the judiciary is their ‘get out of jail free’ card?

After all, some of the expert reports cited in the Egrant findings outright state that other reports including for Magistrate Natasha Galea Sciberras (on kickbacks to Schembri) are ready – and that was in July 2018.