In another EU state, even a whiff of hidden money from a politician would be received with uproar. And it would be justified.

Electing other citizens to represent our interests at a national level is an intimate business; trust is requisite. Importantly, elected officials wield substantial power, not simply over policy, but the nation’s finances. Unless an elected official is not trusted by the people to carry out his duties, doubts of graft will hang overhead, preventing the incumbent from maximising governmental productivity.

The solution is not to resign scrutiny altogether. ‘Let them do whatever they want, as long as I’m happy; is a flawed response: your pockets are affected, too. Individually, there has been material improvement. On a community level, political scientist Edward C. Banfield predicted that amoral familists care very little if they do not see an obvious individual benefit.

Malta has moved on from the impoverished network of villages it was known to be a generation or two ago. Despite the prosperity, his hypotheses are proving true in 21st century Malta. To take an example dear to anthropologist Jeremy Boissevain, the environment in Malta is treated with indifference, albeit significant improvements. Generally, the Maltese do not see any gain from having green, open spaces – save for the hunters. The benefits are profound, but it is the perceived reality.

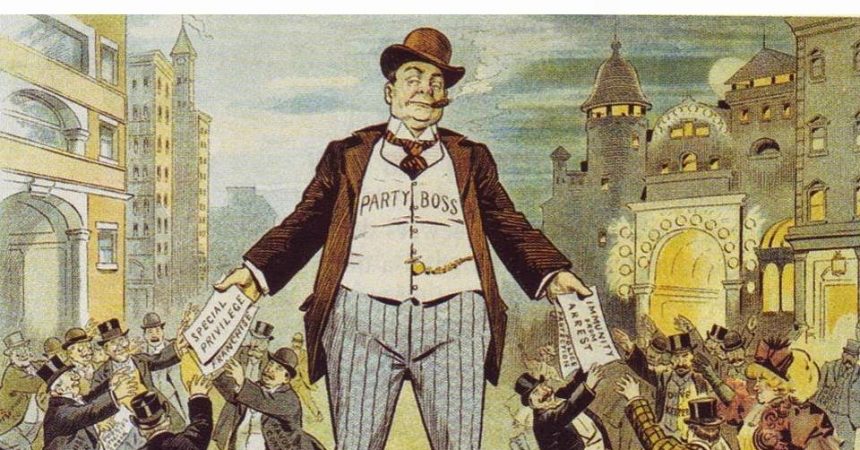

Similarly, the mentality is reflexive in the way public officials are perceived. Before the Malta Labour Party established a framework of patronage on the village level, the Church was mainly responsible for social affairs. Even prior to that still, there was a reliance on a more powerful figure.

Boissevain describes the social network of people in Malta. Unlike the strict relations of Latin America or Sicily, Maltese networks are open to outsiders, just as long as they have the right influence. Decades ago, professionals or civil servants were looked up to simply for their status. More importantly, because citizens saw that they could benefit simply from knowing a person like that.

It would be absurd to lift Boissevain’s sociological analysis and paste it into today’s political sphere. The essence nonetheless remains the same. Once Joseph Muscat and his cabinet have developed a relationship of good old-fashioned patronage with the electorate, effective democratic scrutiny is rendered impossible.

From the point of view of the recipients of those favours, Joseph Muscat, Konrad Mizzi and Keith Schembri have done good by them. If it becomes known that they have extra money hidden in bank accounts abroad, the initial thought isn’t that it has been stolen from the pockets of the electorate. Instead, it can be viewed even positively. The affinity they had with important figures isn’t betrayed by allegation of money-laundering; rather, it is enhanced.

My friend the MP is more powerful than I thought, so I can benefit further – never mind that the enrichment has come at the expense of the same electorate. The assumption is that candidates run for office to service personal needs and then grant residual wealth to the electorate.

Any criticism or questions levelled at those authorities is seen as jealousy for the power they have to grant patronage. It is not seen as the valid scrutiny warranted in democratic societies in adherence to the principle of political accountability. Malta is, in this regard, not a normal European democracy.

This mentality stems from a history of colonial rulers, but also from a fundamental misunderstanding of the workings of a democratic society. Following the recession, a decade ago, European citizens have become ever warier of their politicians. If it is found out that a politician is slipping some public money into his pockets, outrage would ensue.

In Malta, the recession must not have hit so hard; otherwise, the money-laundering allegations would have been met more aggressively by the electorate.