The news that an Italian court handed a prison sentence to Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore managing director Roberto Napoletano for manipulating his newspaper’s sales figures, raises an issue that advertisers in Malta have been complaining about for some years – namely, that these figures are dictated to them by the same newspaper owners, with no independent body to check the veracity of those figures.

It also underscores just how opaque and arbitrary the government’s decision to allocate public funds to help print media is proving to be, and even though the future of independent news in Malta warrants an open and inclusive discussion, few seem willing to engage in one.

The curious case of Il Sole 24 Ore

Last week, Roberto Napoletano, the former managing director of Il Sole 24 Ore, was found guilty of “false corporate communications” and “market information manipulation”. In short, he was convicted for having disseminated false data on the sales and the distribution of the newspaper, to influence the selling price of advertising space.

The newspaper’s financial problems had been ongoing for years, but in 2016 the Milan prosecutor’s office launched an investigation into the newspaper now suspected of false accounting.

The investigation started following a detailed report by one of the newspaper’s own journalists, Nicola Borzi, who suspected that an English company that managed part of the digital subscriptions for Il Sole 24 Ore was also being used to inflate the number of subscriptions.

This suspicion was further fuelled by the fact that, according to the data collected by ADS, a Milan-based company that collects newspaper sales data, the number of digital subscriptions that Il Sole 24 Ore sold as a “package” – that is, not to individual subscribers but to companies that then, in turn, distribute them to individuals – was completely disproportionate to the overall Italian average.

Lack of corroboration

In Malta, we have no way of knowing what the current print distribution or subscription figures are. Advertisers have to rely on the figures given out by the same newspapers, and unlike digital media, where advertisers can check the veracity of numbers given out, there is no way of doing this with print media.

The latest Media Pluralism Monitor report noted that in Malta “The print market is unregulated, and no data is collected regarding both the market share, as well as circulation and audience/readership numbers. Thus, a thorough assessment of this sector is not possible.”

In October 2021, an investigation by Lovin Malta revealed that Progress Press, which is part of Allied Newspapers that publishes The Times of Malta and The Sunday Times of Malta, had for several years allegedly inflated figures on the number of printed copies in invoices to the publishers and advertisers of magazines inserted in The Sunday Times.

The investigation found that on its invoices Progress Press used to bill magazines for 40,000 printed copies. Yet multiple unconnected sources, including sources within Allied Newspapers, told Lovin Malta that the actual circulation of the print newspaper hovered at a bit more than half that figure, and that was being generous.

Allied Newspapers officials strenuously denied the story, with Paul Mercieca, chairperson of the board of directors, branding it as “riddled with insinuations and inaccuracies” but provided no evidence to back his claims.

What we do know

Advertising revenue, which is what newspapers would have traditionally relied on to cover most of the costs of running a newsroom, has declined all over the world. This was something that both the editors of the Times of Malta and Malta Today had already acknowledged in 2019, well before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic that aggravated matters further.

Moreover, the way news is consumed in Malta has changed dramatically.

In June last year, a survey commissioned by the President of Malta for his ‘State of the Nation’ found that out of 1,064 adults a mere 3% of respondents said they read newspapers. Based on the national statistics at the time, estimated the Maltese adult population at 441,186, thus translating to only around 13,000 people that read newspapers at all.

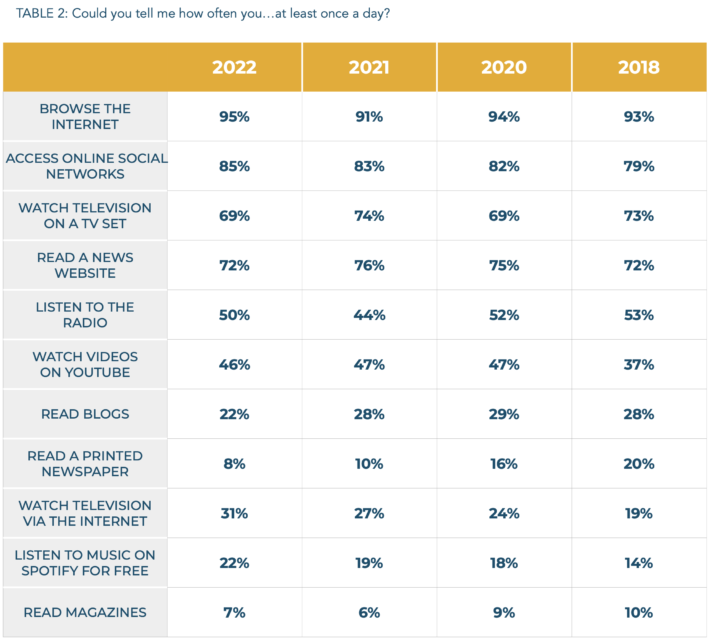

A survey published by MISCO in March this year found that only 8% of Maltese people read printed newspapers while 72% consume news via websites when compared to the previous years. The data indicates that since 2018 the percentage of people who read a newspaper has been getting progressively smaller.

Results of the MISCO survey on social media habits. Source: MISCO Social Media Usage Trends report 2022

Malta has four daily newspapers (Times of Malta, The Malta Independent, L-Orizzont, and In-Nazzjon), one bi-weekly paper (MaltaToday), and six Sunday papers (Sunday Times of Malta, Malta Independent on Sunday, MaltaToday, Il-Mument, It-Torċa, and Kullħadd), and recent survey data suggests that they are all competing for an ever-shrinking market.

More questions than answers

This brings us back to the government’s announcement to allocate €500,000 to help print media cope with the rise in the cost of paper. Like most official announcements, the government’s press release was a simple statement about the decision, devoid of any detail, and which was bound to raise more questions than answers.

We don’t know how the government plans to distribute these funds or what criteria it is going to use to do so. Will those newsrooms that print newspapers be given a fixed sum irrespective of how many copies they print and distribute? How does the government plan to ensure that these funds are used exclusively for printing? Will Malta’s political parties also benefit from this scheme, as they did for the COVID-19 aid package, despite their enormous debts and tax dues?

These are issues that have been repeatedly flagged in international reports that stress the need for transparency and objective criteria for state funding of the media. Upon the government’s announcement, the international press freedom organisation Reporters without Borders (RSF) pointed out that public funding for media must not discriminate and must be based on transparent and objective criteria.

As with almost everything else in Malta, negotiations were held behind closed doors, with only those benefitting from the funds promoting the initiative. Saviour Balzan, whose media companies are big beneficiaries of government contracts even wrote that he was a catalyst for this agreement.

Transparency, objectivity, oversight

A UNESCO policy brief published in May looks at media viability and lists as one of its conclusions the need to “ensure that government advertising is independently and transparently allocated, based on objective criteria. This may require oversight boards as well as stringent regulations and full transparency.”

The recommendations adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe to Member States on promoting a favourable environment for quality journalism in the digital age on 17 March of this year also noted that “any subsidies or other forms of financial support should be granted based on objective, equitable and viewpoint-neutral legal criteria, within the framework of non-discriminatory and transparent procedures, and should be administered by a body enjoying functional and operational autonomy, such as an independent media regulatory authority.”

We have yet to see anything even vaguely resembling an oversight board or an independent media regulatory board in Malta; and when the issue of lack of transparency in state aid for independent media is raised, it is misconstrued as an attack.

Should it not be abundantly clear: no one is advocating that print media should not get help, or that newspaper print copies should be done away with altogether. The issues being raised here are that the help should be repurposed to reflect the change in the way people consume their news, it should be inclusive of all types of independent media and transparent in its criteria.

In a tweet announcing the financial aid, Robert Abela wrote about the decision “to allocate a significant sum to support the work of printed journalism in Malta. The government will continue to support journalism and its important role.”

Fine words, except that if the prime minister were serious about his support of the important role of journalism, he would have adopted the press freedom recommendations of international bodies and of the Daphne Caruana Galizia public inquiry a long time ago.

The problems arising from government funding of the media were already apparent when the government offered a direct aid scheme to media houses over and above the COVID-19 wage supplement. An analysis of the eligibility criteria by Lovin Malta concluded that it was party-owned media that benefitted the most, and independent media never disclosed the sums they received.

In a meeting with newspaper publishers & the IĠM on the increased costs faced by the sector due to intl events, we agreed to allocate a significant sum to support the work of printed journalism in #Malta. @MaltaGov will continue to support journalism & its important role. – RA

— Robert Abela (@RobertAbela_MT) May 21, 2022

These issues were also noted during one of the Daphne Caruana Galizia Public Inquiry hearings when, as the covid relief funding was being explained to the board by Sylvana Debono, the then president of Malta’s Institute of Journalists (IGM), one of the members of the board commented saying “this is not how funds should be distributed”.

The board’s observations appear to have yet again gone unheeded. Therefore no matter what Prime Minister Robert Abela says about his support for journalism, the arbitrariness and opacity of this latest funding package make it look less like help and more like leverage.