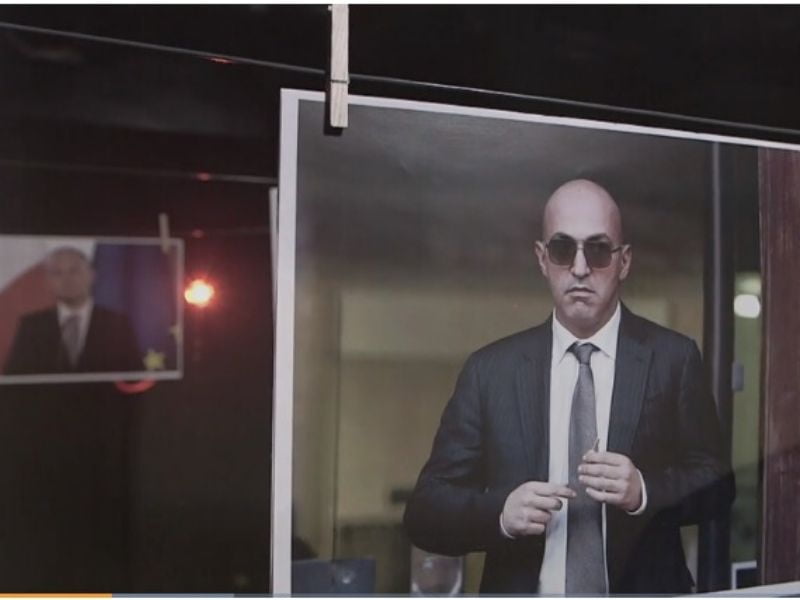

Last Monday’s decree handed down by magistrate Rachel Montebello in the compilation of evidence against Yorgen Fenech, who is accused of commissioning the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia, is the latest attempt to deal with complaints about media coverage of the proceedings.

The decree was in response to three written submissions this month alone. At the beginning of the month, the Attorney General objected to a blog by university lecturer Simon Mercieca that allegedly disparaged the prosecutor, the Deputy Attorney General. Two weeks later, Fenech’s lawyers complained about an article published on the satirical website Bis-Serjeta.

Fenech’s lawyers also separately filed a legal application claiming that intense, damning media coverage is detrimental to their client’s presumption of innocence and right to a fair hearing, particularly since Fenech would eventually be tried by jurors who might be conditioned by media coverage. They asked the court to take “all necessary measures” to “safeguard the correct administration of justice and especially the fundamental rights of the accused”.

It’s a point that was also made earlier this month by another lawyer representing Fenech, Wayne Jordash of London’s Global Rights Compliance, who engaged in a public spat with the Council of Europe’s rapporteur Pieter Omtzigt.

This came about after the rapporteur wrote in his report that he had declined to meet the lawyer who had written to him requesting a discussion on how Omtzigt might “intervene (whether with the Maltese government, media or otherwise) in line with your mandate, to protect the integrity of the trial process, and to ensure Mr Fenech’s right to a fair trial (especially one based on the presumption of innocence)”.

In a twelve-page decree, magistrate Montebello grappled with the issue and then rested on judicial discretion and proclamation rather than the blunter instrument available in criminal law, Article 517. Yet this has created confusion rather than provide clarity to journalists.

The decree said that ensuring Fenech’s right to presumption of innocence “requires” that there be no media-style debates or discussions (on TV or online) about the proceedings or their outcomes, and no public statements that specify or suggest that Fenech is “guilty” of the assassination.

It also called for reporting on proceedings to be limited to “the media, [and] not private persons” to avert reportage that would be “prejudicial or inaccurate”.

This makes this part of the decree instructional, not a court order grounded in specific and actionable legal provisions.

Then, in the same decree, the magistrate ordered the registrar to proceed against Simon Mercieca and the author or publisher of Bis Serjeta for contempt of court, which is punishable by up to a month’s imprisonment.

Such an order might lead journalists, bloggers or broadcasters to consider that if they do anything that fails to meet the ‘instructional’ part of the decree, they may also end up being similarly charged with contempt of court.

Two troubling issues emerge from this context. First, the distinction implied in the decree between “media” and “private persons” has little basis in law.

The law does not define, or limit, who is a journalist or what counts as ‘media’. Anyone can be a journalist by virtue of practising as one, and anyone can be a publisher – and hence media – by engaging in publishing, irrespective of whether it’s someone writing a blog or working for a newspaper or TV station. (Of course, everyone bears equal responsibility before the law – even someone who comments on Facebook can be held liable under the Media and Defamation Act.)

In this sense, the distinction is discretionary, even arbitrary, and coupled with the order to prosecute Mercieca and the author of Bis-Serjeta – and here’s the second issue – the decree is likely to have a chilling effect on journalists covering the story, particularly bloggers and others outside the mainstream “media”. This is likely to foster an element of self-censorship.

Legal sources consulted by The Shift also maintained that the law does not seem to provide the scope to the criminal court to order the registrar to prosecute Mercieca and author of Bis-Serjeta for contempt of court.

Although the magistrate argued in the decree that lawyers ought to be protected because of their designation as “officers of the court”, the sources said that in the context of blogs or articles in which the lawyers might have allegedly been disparaged because of their work, the remedy for the lawyers would ordinarily have been to file for libel.

In a broader way, the magistrate faced the difficulty of having limited legal instruments to deal with this situation. In fact the only legal provision in criminal law that allows a court to impose a so-called gagging order is Article 517, which empowers the court to ban any publication or broadcast of proceedings of a case.

This provision was intended for an earlier era when prosecutions would be measured in months, not years. Now, it takes several years or more for a weighty case in the criminal court to progress from arraignment to conviction or acquittal. Imposing Article 517 for years would impact freedom of expression.

Lawyers told The Shift this provision has only been employed a handful of times in the past 30 years or so.

In her decree, Montebello mentioned Article 517 in the analysis but then did not issue an order on the back of it – instead she opted for recommendations not based on any specific law.

Yet these are discretionary, and as such have an insidious chilling effect.

This shows the need for a smarter regulatory regime perhaps modelled – as recommended in 2018 by magistrate Joe Mifsud – on the UK’s Contempt of Court Act, which makes it an offence for publication or broadcast that may “interfere with the course of justice in particular legal proceedings regardless of intent to do so.”

The law qualifies that the rule applies to “publication which creates a substantial risk that the course of justice in the proceedings in question will be seriously impeded or prejudiced.”

Such a law would make the interaction between freedom of expression and the administration of justice more sophisticated, and less reliant on judicial discretion.

What a mess when the law tries to ‘adjust’ free speech. It only makes things worse. Let society deal with the issue not the law. Give the pubic all the facts uncensored and then let the people make up their minds as to what is right and wrong… they are not children to be guided.

All said, with one exception. Once a crime breaks the public good order and the public peace