Lionel Gerada, the former canvasser of Konrad Mizzi who dished out millions of euros in taxpayers’ money to a close group of party organisers as director of events at the MTA, is attempting to bury his criminal past by blocking access to court judgements against him.

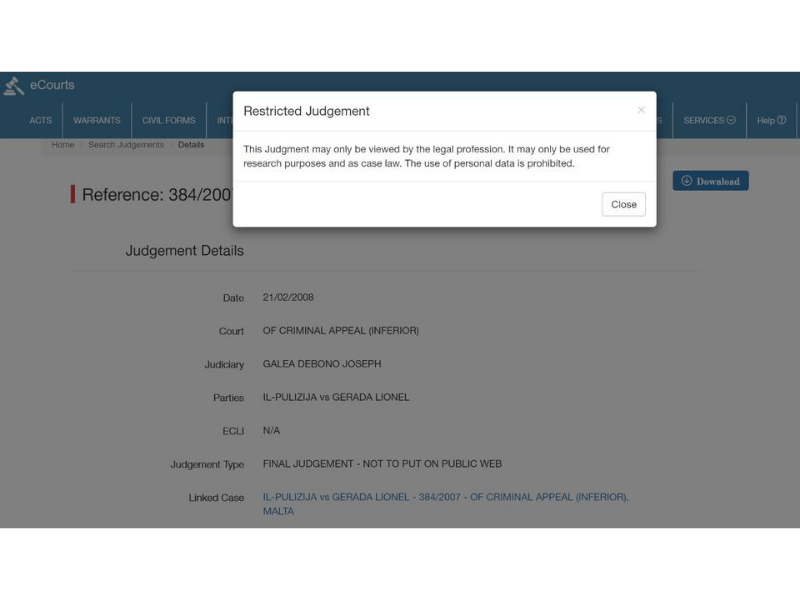

A skim through the e-courts website shows that two judgments by the criminal court involving Lionel Gerada have now been ‘removed’ from public access.

Lawyers speaking to The Shift note that the judgements are now only accessible to lawyers, given that these are highlighted in red. According to the website, highlighted judgements have restricted viewing, and “personal details mentioned in these judgements are not to be published and are considered as personal data in terms of the GDPR.”

Other judgments against Gerada that were concluded by the small claims tribunal are still accessible to the public.

The GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) is the EU’s legal framework regulating the processing of individual personal information within the European Union.

Lawyers who spoke with The Shift note that the arbitrary manner in which judgments that are meant to be accessible to the public are being restricted is a concern. They noted that while EU data protection laws — including GDPR — include concepts such as the right of erasure, these should not be taken by a government as carte blanche to ignore its other legal obligations, like publicity of judgements.

Gerada, who was given a highly sensitive post at the Malta Tourism Authority with a multi-million euro budget that tripled under his watch, filed the request or used a lawyer to have his sentences removed from the public domain.

The Shift had revealed how former DJ Lionel Gerada was entrusted to handle millions of euros under the auspices of the MTA despite having a criminal record that involved embezzlement of funds and falsification of documents.

He was also given a suspended sentence after getting involved in a fight with a group at the Zabbar feast.

The two court judgements Gerada wants hidden refer to a case where he admitted to charges related to the embezzlement of funds and using false names. He was handed a conditional discharge by then magistrate Giovanni Grixti.

The other item Gerada wants blocked from the e-courts website is a sentence handed down by the court of appeals confirming a judgement where Gerada was found guilty of falsifying documents, and caught driving a motorcycle without licence or insurance, and with false number plates.

His criminal record was also mentioned at a Public Accounts Committee hearing looking into the MTA’s unprecedented spending spree. MTA Chairman Gavin Gulia was grilled by PAC members on how someone with a past like Gerada’s was allowed to be employed in such an important role.

The PAC was also presented with a letter from Lionel Gerada’s lawyers claiming their client is “a person of good repute”, and dismissing his previous criminal convictions as “teenage folly”.

The letter was signed by Gianluca Caruana Curran and Charles Mercieca, the same lawyers acting as defence counsel to Yorgen Fenech, the suspected mastermind in the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

“Data protection law warped”

A person’s right to be forgotten or to have records completely removed from the public domain conflicts with the legal requirement for court judgements to be made accessible to the public.

The Malta IT Law Association had in 2018 expressed concerns over reports of private individuals successfully requesting court cases that had been decided against them to be deleted from the online database.

The association published correspondence with Minister Owen Bonnici explaining that “removal of personal data from an online service administered by Government and which contains public records, especially court judgments, cannot be simply compared to delisting from a search engine”.

In 2014, the European Court of Justice famously coined the expression “the right to be forgotten”, a concept which later found its way into GDPR in a judgement against Google. The case involved a person annoyed at having his court record appear in search hits on Google. The Court held that a person has a right to request the removal of personal data in certain circumstances, including by Google.

However, the Court did not order the deletion of the actual judgements or the news articles relating to the offence. The right of erasure is not absolute. Court judgements, for example, are normally published to comply with a very basic legal and democratic obligation to publicise not just laws but also judgements by the Courts.

The process for the removal of judgements from public access appears not to follow objective and public criteria stemming from law, which means it is both arbitrary and potentially subject to abuse.

The issue with the removal of court judgments re-emerged recently when reports in the media suggested Aldo Cutajar, who was recently charged with money laundering, had previous judgements related to misappropriation of public funds removed from public domain.

Cutajar served as Malta’s Consul General in Shanghai, and is the brother of Mario Cutajar, Malta’s head of civil service.

In a Facebook post on 16 August, former Justice Minister Owen Bonnici denied claims made by Jason Azzopardi that the minister had ordered Cutajar’s sentence to be removed from online judgements. Bonnici referred to a board made up of five individuals who review the requests of those wishing “to be forgotten”.