The publication of the Egrant inquiry report has raised more questions than answers. It failed to address the question on everyone’s mind – who owns Egrant? And the decision by the Constitutional Court ordering a copy to be given to Opposition Leader Adrian Delia was based on an infringement of his human rights, which raises further questions on the conduct of the Attorney General and the scope of the inquiry.

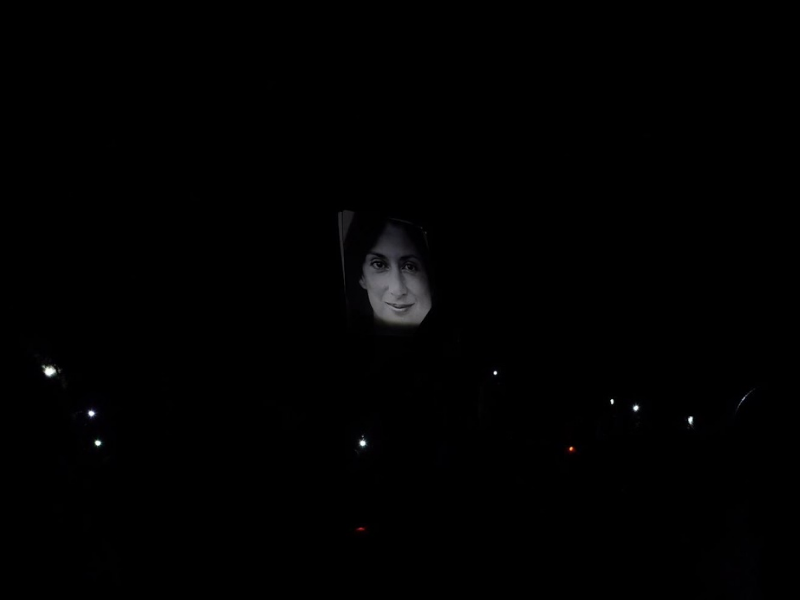

After the Opposition Leader decided to publish the full report, The Shift spoke to former European Court of Human Rights Judge Vincent De Gaetano to unravel fact from misconception as to the scope of the inquiry by then Magistrate Aaron Bugeja, who was later promoted to Judge. The inquiry looked into the claim by assassinated journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia that the third company exposed in the Panama Papers belonged to Michelle Muscat, wife of Joseph Muscat – the Prime Minister forced to resign in disgrace amid a sea of scandal.

De Gaetano is critical of Bugeja’s approach when “sticking to the narrow parameters of the report filed before him by the Police Commissioner, which in turn followed to the letter the request made to the police by the Prime Minister’s lawyers”. In contrast, he raises the case of the murder of Raymond Caruana and the frame-up by the police of Pietru Pawl Busuttil in the 1980s.

He disagrees with Bugeja’s apparent dismissal of evidence as related to “matters beyond the scope of the inquiry”, saying this was inconceivable. He also says Bugeja was wrong to say that evidence contained in Daphne Caruana Galizia’s laptop could be inadmissible.

He raises concern on a number of other issues, including Attorney General Peter Grech’s “blatant disregard of his investigative functions”, questioning Grech’s decision to “hand everything on a silver salver to the Prime Minister”.

Was the Egrant inquiry nothing more than a futile exercise to serve the Prime Minister’s agenda?

On the Egrant magisterial inquiry…

Hold on. The expression “magisterial inquiry” is not even used in the Criminal Code. The Egrant inquiry was an in genere inquiry.

What does in genere mean?

Basically, and in layman’s language, it refers to the generality of the circumstances which point to the possible commission of an offence, and is conducted with a view to arriving at the truth by conserving all the evidence available and, if possible, identifying who may have committed a particular offence or a number of offences.

So, at this stage, no one will have been formally charged with an offence, right?

Absolutely correct. At this stage, there are only pointers, reasonable suspicion as to the possible commission of an offence or offences. This reasonable suspicion may be based on material traces, like the tell-tale signs of a break-in, or on the contents of documents or on the information known to persons who are then summoned by the magistrate to give evidence before him. Remember that, at law, the word ‘document’ does not mean simply a paper document but any material thing – a fingerprint, a computer, a weapon, shrapnel from a bomb – which, when properly analysed, if necessary with the help of experts, may shed light on what happened and, if possible, on who caused a particular illegal act to occur.

Is the in genere the only type of inquiry in which a magistrate may be involved?

No, there are others. Under the Criminal Code a magistrate must conduct an inquiry into any sudden, violent or suspicious death, or indeed into any death where the cause is unknown – a death which cannot be certified by a medical practitioner. The term ‘violent’ here is not meant to refer to death at the hands of a murderer or a burglar – that would invariably lead to an in genere – but, for instance, when a person falls to his death from a height or is crushed to death by machinery at his place of work. Here, the inquiry, technically called an inquest, is triggered not so much because there are circumstances which point to the possible commission of a criminal offence, but rather because it is unclear as to how a person died. Here we are closer to the English coroner’s work.

The principal purpose of the inquiry in such a case is to discover the precise circumstances surrounding the death. Likewise, under the Criminal Code, an inquest must be conducted by a magistrate when any person dies while in a place of custody, like in prison, or while in police custody or while detained at Mount Carmel upon an order of a court of criminal justice.

When an individual is undergoing proceedings before the court of criminal inquiry, what kind of inquiry is that?

I know it may sound confusing, but it is really quite simple. When a person is arraigned in court, whether by writ of summons or under arrest, charged with an offence which carries a certain degree of punishment, the court of magistrates sits as a ‘court of criminal inquiry’ – in Maltese, it is referred to as kumpilazzjoni tal-provi. But this has nothing to do with in genere inquiries or inquests. In this case, the magistrate acts primarily in an adjudicating role and not as investigator: he/she must decide whether the evidence adduced by the prosecution is sufficient to warrant indictment by the Attorney General before the Criminal Court. Nevertheless, even here we find some investigative functions – the Attorney General may send back the record of the proceedings, the record of the kumpilazzjoni, to the court for further evidence to be collected or witnesses to be examined or re-examined.

In the Court of Magistrates as a Court of Criminal Inquiry, the procedure is predominantly adversarial; in the in genere inquiries and inquests the procedure is said to be inquisitorial; that is, investigative. Unfortunately, the word ‘inquisitorial’ conjures up images of the Roman, or worse, the Spanish Inquisition.

And how is the ongoing public inquiry into the murder of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, presided by Judge Michael Mallia, Chief Justice Emeritus Joseph Said Pullicino and Madam Justice Abigail Lofaro, different to other inquiries?

That inquiry is a totally different kettle of fish. It was set up in terms of the Inquiries Act. This type of inquiry has nothing to do with the Criminal Code.

What are the main differences between an in genere inquiry under the Criminal Code and an inquiry under the Inquiries Act?

There are a number of differences. The scope of an in genere inquiry and the powers of the magistrate in such an inquiry are determined primarily by the Criminal Code.

On the other hand, in an inquiry under the Inquiries Act, both the scope of the inquiry and, to a large extent, the powers of the person or persons conducting such an inquiry, are determined by the terms of reference drawn up by a minister or by the Prime Minister.

An in genere inquiry can only be conducted by a magistrate, whereas any person or number of persons, and therefore not necessarily members of the judiciary, can be appointed to conduct an inquiry under the Inquiries Act.

Most inquiries under the Inquiries Act are held in private. The inquiry being conducted by two retired members of the judiciary – Mallia and Said Pullicino – and by a serving member – Lofaro – is public only because the terms of reference state so, following months of pressure by European institutions for such a public inquiry to be held.

So is an in genere held in private? Is it a secret inquiry?

Interesting question. Yes and no. The Criminal Code does not expressly say anything about the secrecy or confidentiality of an in genere inquiry. The ‘secrecy’ surrounding an in genere is more a question of sensible practice rather than of law. For example, when the magistrate goes to the scene of a fatal accident to describe the scene in detail for the purposes of the report that is subsequently drawn up, he/she does so in full public view. When witnesses are heard, it is not uncommon to have police officers present, and if the witness is, for instance, heard at his residence there may also be members of the family present. A witness is certainly not bound to secrecy or to keep confidential what he has told the magistrate.

On the other hand, the law provides that the final report of the in genere, called the procès-verbal, together with the record of the proceedings – that is, evidence, documents collected and so on – is to be sent to the Attorney General. Copies of this report and of anything contained in the record of the proceedings may only be given to third parties at the discretion of the Attorney General. This is intended to allow the Attorney General time to go through the entire proceedings and, if necessary, either draw the attention of the police to further inquiries they should carry out, or send back the record to the magistrate for further investigation.

Should the Attorney General have given a copy of the Egrant report to the Prime Minister?

Certainly, he could. The question is whether he should have done so given the circumstances surrounding the inquiry. Furthermore, whether he should have done so in less than 24 hours.

Even if the Attorney General had apportioned the entire procès-verbal and record of the proceedings among all his law officers, there was no way they could have trawled though the findings in less than a day. So, in practice, the Attorney General simply bounced the whole thing into the Prime Minister’s lap with blatant disregard for his investigative functions.

The Egrant report has, as we now know, a great deal of information connected to other possible actors on the corruption scene, many of whom are seen to be quite close to the Prime Minister personally or to his office. It was simply irresponsible for the Attorney General to hand everything on a silver salver to the Prime Minister.

The Attorney General has claimed that his function is not to investigate but to prosecute.

The Attorney is being disingenuous when he says that. The fact that he has the power, expressly stated in the law, to send the record of the in genere back to the magistrate for further investigation shows that he does have investigative powers. Moreover, another provision of the Criminal Code provides that the Attorney General may produce, at a trial, other evidence besides that resulting from the proceedings before the Court of Criminal Inquiry – the kumpilazzjoni. This ‘other evidence’ does not fall from the sky.

The Attorney General does have investigative powers, even if limited. Of course, you cannot expect the Attorney General to put on a deerstalker cap and to go, magnifying glass in hand, to investigate personally. Most of the investigation is done for him by others, notably by magistrates in an in genere – the Attorney General, like the police, can trigger such an inquiry at any time – or in the course of proceedings before the Court of Criminal Inquiry. As the most senior public law officer – a pinnacle he now has to share with the State Advocate – he has a duty to uphold the law and to report to the police all suspicious activity and to insist that the police carry out their duty according to law.

Was the fact that the Attorney General acted hastily or irresponsibly the reason why the Constitutional Court ordered that a copy of the Egrant report be given to the Opposition Leader?

There were two reasons for this decision. First, the Constitutional Court held that the discretion that the Attorney General has in issuing copies of the procès-verbal does not of itself breach fundamental human rights, but that the way in which that discretion was exercised in this particular case – by the Attorney General giving a copy to the Prime Minister but refusing to give one to the Leader of the Opposition – was in breach of the latter’s right and freedom to receive and impart information, given the Leader of the Opposition’s constitutional role.

Second, the Constitutional Court also held that the way the Attorney General exercised his above-mentioned discretion had also breached the Leader of the Opposition’s right not to be discriminated on political grounds in the enjoyment of the right and freedom to receive and impart information. In its judgment, the Constitutional Court specifically made reference, in the context of political discrimination, to the fact that it was not only the Prime Minister who had been given a copy of the procès-verbal, but also the Prime Minister’s personal lawyer and the Minister of Justice, and copies had somehow found their way to the government’s Head of Communications and three other Cabinet ministers who had quoted from that procès-verbal in the course of proceedings in which they were involved.

In short, the Attorney General had discriminated on political grounds, and therefore unlawfully, when refusing to give a copy to the Leader of the Opposition when so many on the other side of the political divide had a copy.

What powers does a magistrate have in an in genere inquiry?

Since the whole object of such an inquiry is to arrive at the truth, the magistrate has extensive investigative powers, certainly more than the Attorney General. The magistrate may order the arrest of any person whom he/she believes to be guilty of the offence or offences which may have been committed, or indeed even of any person ‘against whom there is sufficient circumstantial evidence’. The magistrate may order the seizure of ‘any papers, effects and other objects generally’ which he/she may think necessary for the discovery of the truth; and may also order the search of any premises, even belonging to third parties, if there is enough evidence suggesting that other evidence may be found in those premises.

According to the Egrant report, Magistrate Bugeja was informed by experts who had analysed computer data that there was evidence suggesting that Nexia BT and Pilatus Bank were involved in “probable money laundering and sanction evading activities” involving “both citizens of Malta and elsewhere”. It appears that his direction to experts was that “these matters fell outside the scope of the current investigation”. This resulted in leads not being followed through. Was this correct?

It is inconceivable that a magistrate who, for example, may be investigating a possible burglary but then, quite by chance, comes across evidence suggesting that a totally unrelated murder has been committed, should simply ignore the evidence regarding the murder.

One would expect that in such a situation the magistrate would either expand his investigation to cover the possible murder or, as a minimum, immediately and expressly order the police to file a new report with the duty magistrate, so a new in genere inquiry can immediately be undertaken. It is unclear to me what steps Magistrate Bugeja took the moment he was faced with the experts’ report, although it must be said that in the concluding part to his report he did order that an authentic copy of the experts’ report be served upon the FIAU, and also ordered the Commissioner of Police to further investigate the conclusions of those experts.

It must also be said that the Criminal Code is silent as to what should be done in a similar situation, but such silence is not ground for inaction, but rather enables a magistrate to be more proactive than normal in the search for the truth. In the late 80s, three magistrates were investigating three separate, albeit related, incidents – the shooting at the façade of a PN club, the murder of Raymond Caruana, and the alleged ‘finding’ of the murder weapon in the farm of Pietru Pawl Busuttil.

Although not specifically provided for in the law, they decided to pool resources. Magistrate Albert Borg Olivier de Puget ‘handed’ his inquiry to Magistrates Gino Camilleri and Geoffrey Valenzia who were investigating the murder of Caruana and the finding of the murder weapon. These two then proceeded to conduct one joint in genere inquiry and drew up one procès-verbal. In this procès-verbal they exonerated Busuttil by pointing out to the police frame-up in his regard.

Meanwhile, however, Busuttil had been arraigned before the Court of Criminal Inquiry charged, among other things, with the murder of Caruana. The government, keen to make sure that the conclusions of Camilleri and Valenzia should not be used in the proceedings against Busuttil, slipped in an amendment to the Criminal Code allowing the Commissioner of Police to challenge the validity and admissibility of a procès-verbal.

It should be recalled that from the moment it became clear that there had been a frame-up by the police, the Attorny General had refused to assist the police any further in connection with the proceedings against Busuttil. The Attorney General had even taken the extraordinary step of constituting himself as amicus curiae – friend of the court – in the proceedings against Busuttil, which were before Magistrate David Scicluna, so as to intervene only if and when the court needed his assistance. Eventually, Busuttil was discharged by the Court of Criminal Inquiry for want of sufficient evidence for an indictment to be filed, and the new incoming government repealed the amendment allowing the police to challenge a procès-verbal.

That said, the impression one gets, even from the rambling introduction with references to the historical antecedents of the current institute of the in genere, is that in the Egrant inquiry the magistrate was overly concerned with sticking to the narrow parameters of the report filed before him by the Commissioner of Police, which in turn followed to the letter the request made to the police by the Prime Minister’s lawyers.

The Egrant report shows that in the course of exchanges with the German authorities on Daphne Caruana Galizia’s computer, the magistrate expressed the view that because the chain of possession of these devices could not be ascertained, then it was likely that these computers could not be used as evidence. Was this the right course of action?

Not quite. A broken or unascertainable chain of possession of a document – remember that ‘document’ means anything material that may shed light on what happened – does not render that document inadmissible as evidence, and this is especially so in an in genere inquiry. It may at most affect the probative value of the document in question at the trial stage.

What do you mean by ‘probative value’?

Probative value is the weight to be given to a particular piece of evidence, whether it is a document or sworn testimony, at any of the adjudication stages after the Court of Criminal Inquiry stage, that is after the kumpilazzjoni. One generally speaks of the credibility of a witness and the probative value of a document. But an unbroken or unascertainable chain of possession does not affect the admissibility of the document.