Of all the insults Daphne Caruana Galizia had to put up with in her lifetime, the most enduring was that of a wicked witch – is-saħħara tal-Bidnija – “spewing bile” as government representatives, its appointees and favourite journalists have said of her.

This is hardly surprising: Malta’s culture remains deeply misogynistic where women are routinely insulted and dehumanised, not only by men but also by complicit women who enable or justify gross male behaviour.

The current administration can bandy about trendy words and phrases such as “the most feminist government in history” or “gender equality”, but nothing could be further from the truth.

Caruana Galizia was not the first nor will she be the last person to suffer misogynist insults. Ask PD MP Marlene Farrugia, PN MEP Roberta Metsola or activist Tina Urso what they have to put up with, but the term “witch” stuck with Caruana Galizia for the entirety of her career. This is particularly telling for a number of reasons.

Before digging a little deeper, let’s start with the word itself: Witch. This is an age-old insult used to police women’s behaviour. Add to this the label “whore” and you’ve got two convenient terms employed to shame women into socially accepted behaviour.

The ‘whore’ transgresses the norms of sexuality, while the ‘witch’ transgresses the norms of female power and this, unlike the ‘whore’, is far more threatening, particularly for men. Throughout history, the witch is either considered a destabilising, dangerous villain or a powerful protagonist, and the description one chooses for her depends entirely on one’s view of women.

Even though there are many types of witches that capture our imagination both in real life and on screen, here we will only be addressing the classic evil hag given that, in the limited Maltese imagination, this is what was meant when Malta’s foremost investigative journalist was called a “witch”.

The story of the witch goes back thousands of years, originating in ancient Mesopotamia and in the Greek tales of Hecate. These were goddesses that had the ability to give and take life and for this they were worshipped.

It was only when monotheistic religions gained prominence and belief centred around a single male deity that women were often cast as ‘other’ villainous protagonists. With men dictating social norms, of course the witch, at the very least, was going to be ugly, old and cruel because for starters, women must be neat, young and as obedient and attractive as possible.

Even after her murder, she is not allowed to be human.

The classic image of the evil, aged hag who consorted with the devil predates Christianity. Roman literature describes witches as pathetic creatures who dug in the ground at night and tore animals with their teeth.

The most famous incarnation of this type of witch can be found in Shakespeare’s Macbeth in the form of the three sisters, the “midnight hags”, whose potions were as ghastly as their appearance and who would curse anyone who crossed them.

The witch we learn of as children also fits into this category. She either wants to harm us (Hansel and Gretel) or is simply ‘jealous’ of the young, pretty ingénues. Think of the classic fairy tales of Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Janice and Owen (when they were a thing).

It was however not until the 14th century that the fear surrounding ‘other’ women came to a head. Between the 14th and 18th centuries in Europe, thousands of people accused of witchcraft were put to death. Estimates vary but research puts the number at around 100,000 with around 85% being women.

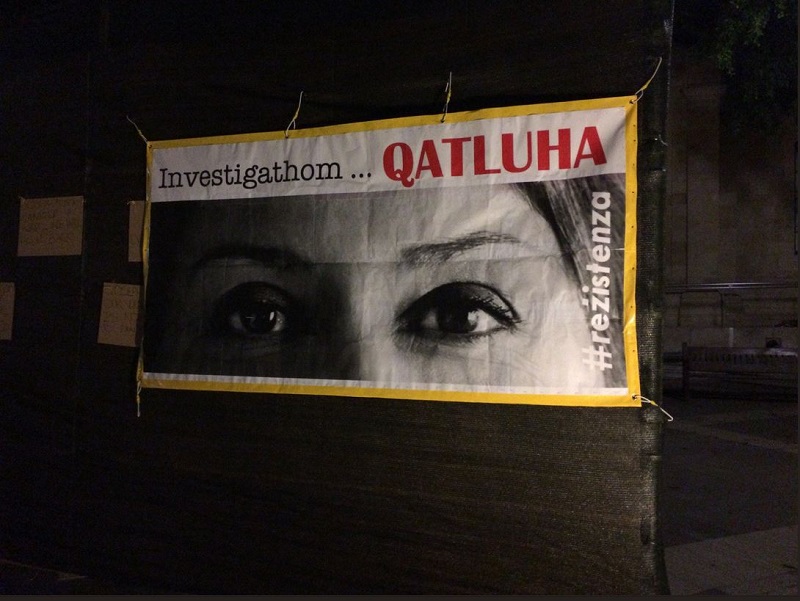

One of the banners put up by Rezistenza Malta after the government blocked off the original memorial.

Sure, some men were accused of witchcraft but they were a minority. And the words we use to describe them – wizards, warlocks, magus – don’t carry the same stigma.

So, what got you killed? Almost anything at this point. Just being female and sexual landed you in trouble. Associating or getting together with other women got you accused of forming a coven in order to party with Satan. You also risked punishment for being poor or for helping the poor.

A large number of women were put to death simply for being the equivalent of today’s midwives. These were often older, widowed women who scraped a living by providing obstetric support, who understood the female body better than their formally-trained male counterparts and who – deep breath – used empirical reasoning and knowledge.

These women presented many layers of threat because, as we know, nothing undermines authority more than the education of the ignorant masses. You also raised suspicion by amassing too much land, wealth, influence but worst of all, knowledge.

If you needed help identifying a witch, Heinrich Kramer, a German prelate published the Malleus Maleficarum in 1486, undoubtedly one of the more twisted and influentially destructive texts ever written about women.

Oh, and if you’re starting to think that politically powerful women were spared, think again because it was not just poor and vulnerable women living on the fringes of society that were singled out.

Joan of Arc led the French to victory against the English and was renowned in France for her purity. But when English leadership couldn’t beat her, they sought to undermine her credibility by attributing her success to demonic influence. Surely it was unnatural that a young woman showed such bravery in battle of her own accord?

Cleopatra was accused of witchcraft, as was Anne Boleyn – Queen of England from 1533 to1536 and the second wife of King Henry VIII. These accusations were an extremely effective way for a woman’s political enemies to discredit her because, as many women found out, there is no definitive way to prove you are not a witch. And in the 21st century we are still not done with the witch trope.

Hillary Clinton was labelled a witch since she was First Lady. Julia Gillard, first female prime minister of Australia, was met with taunts of “ditch the witch” from protesters. Nancy Pelosi, the minority speaker of the US House of Representatives, has faced similar insults, as has Theresa May.

Defeating these outspoken women politically is not enough. They are abominations because they show ambition, so they must be cast out.

It is difficult to comprehend the sheer viciousness of the way villagers and townsfolk attacked those they held to be witches.

For years scholars believed that witch hunts were the sole product of a reactionary, misogynistic Catholic Church, but more recent scholarship suggests that it was their neighbours that women had to fear most.

One such study by Lyndal Roper does not give us a history with a satisfying, obvious villain. Instead, it is crammed with little stories: squabbles among neighbours, family resentments, cantankerous local characters, the manoeuvring of small-time politicians and the creepy psychosexual fixations of magistrates and clerics.

Witch hunts, she argues, were more of a joint venture between lower-level authorities and common folk who yielded to ordinary pettiness, than a coordinated sweeping attack by the Church, although it certainly enabled it. Seen that way, it’s a recurrent pattern and one that is very much thriving in Malta.

The history of witch hunts seen from this angle warns us against glorifying the sense of ‘community’ offered by small towns and villages when the bonds of such communities are often cemented by tormenting their marginal members.

“It is difficult to comprehend the sheer viciousness of the way villagers and townsfolk attacked those they held to be witches,” Roper writes.

Then again, have you lived in Malta?

Is it really that difficult to see how they got started in that direction and how they managed to get so far?

Caruana Galizia was an outlier and, if you are of a certain mind-frame, then she embodied everything that was unnatural and feared.

What? An experienced journalist whose work remained relevant even as times changed? How dare she not enjoy wearing heavy make-up and high heels? Unnatural, ugly even. Goodness, she wrote in a barbed, almost masculine tone? She was aggressive and relentless; fearless, even. Unnatural, cruel.

Even after her murder, she is not allowed to be human.

Caruana Galizia pieced together seemingly unrelated strands of information from her investigations – unnatural, clearly, this superior intellect must be due to outside forces.

She lived all the way out in Bidnija and had two Mastiffs as guard dogs – how mysterious, what spells was she conjuring up on her laptop to hurt our men?

She was an outspoken government and opposition critic and a loving mother; unnatural – a woman cannot be both.

Older, assertive, knowledgeable, authoritative and respected women are still not welcome in a fast-changing world and many forces remain aligned against them.

Punishing witches accomplishes two things: it ends the threat and makes others afraid to follow in the unruly woman’s footsteps.

Not content with physically removing Caruana Galizia from the public discourse (they did not manage to erase her), the government has now launched a coordinated smear campaign in order to undermine her memory and her work.

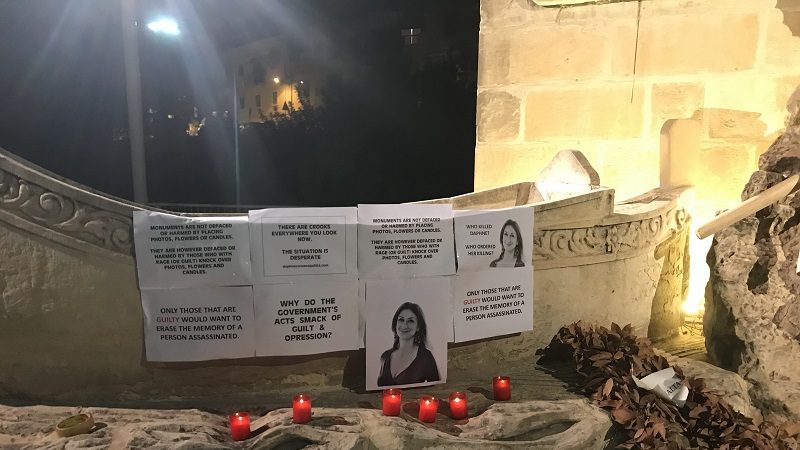

On Saturday, her memorial was not only removed for the second time in days (after numerous attacks on it), but the government actually cordoned-off the area, denying public access to it. Women activists were at the forefront a few hours later, and throughout the night, hitting back by setting up seven memorials around national monuments across the country.

It seems witches are the women with backbone who are here to stay. So too, Caruana Galizia’s legacy.