Latest News

Auditors confirm “significant doubt” on repayment of €15 million MMH bond

Auditors have warned that “significant doubt” remains over the ability of the Mediterranean Maritime Hub (MMH) to re..View More

PL, PN report only half of their problematic finances

Beneath the tension that underpins the latest exchanges between Malta’s major political parties lies a common weak..View More

More delays at Co-Cathedral as Anglu Xuereb blasts “vitiated” multi-million tender

A long-delayed extension of the museum at St John’s Co-Cathedral has encountered a fresh setback after a multi-million..View More

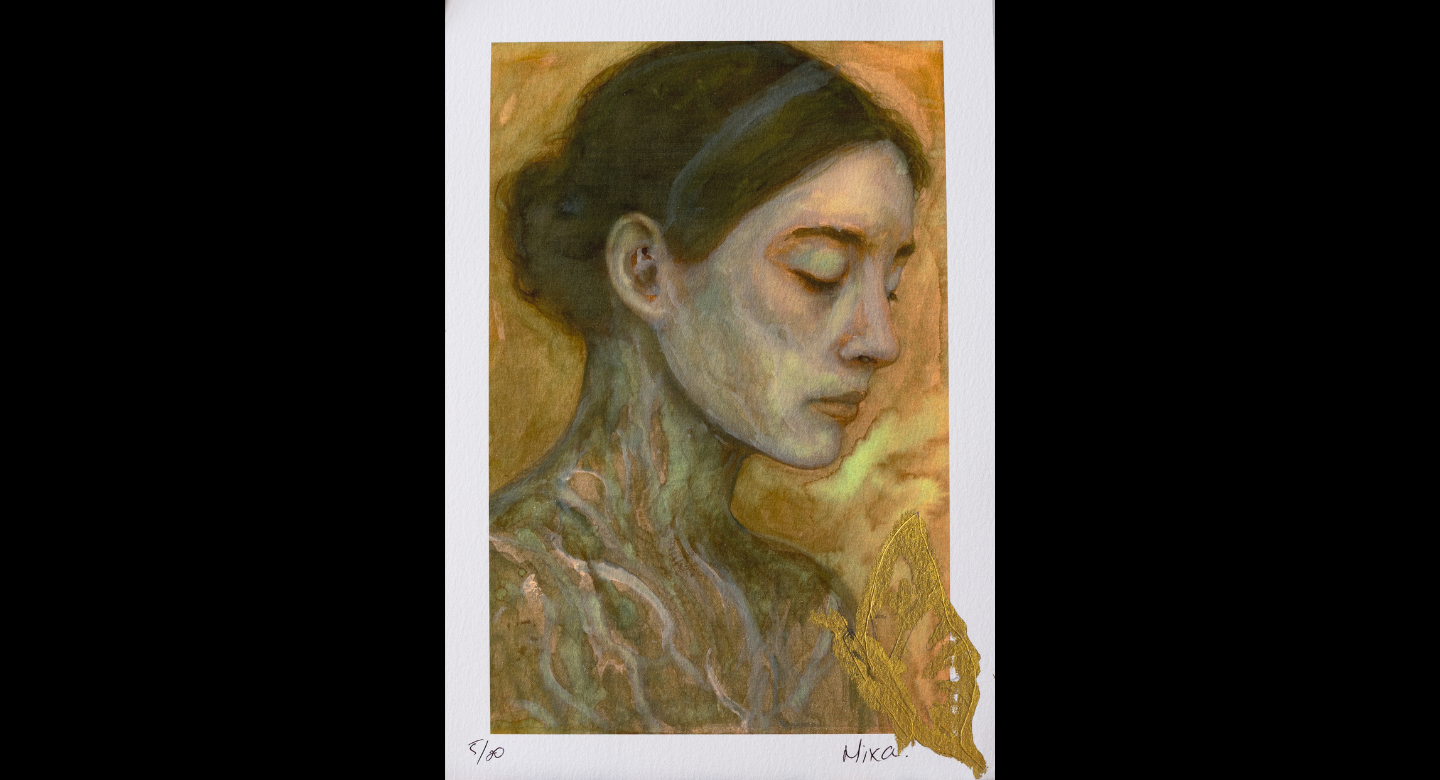

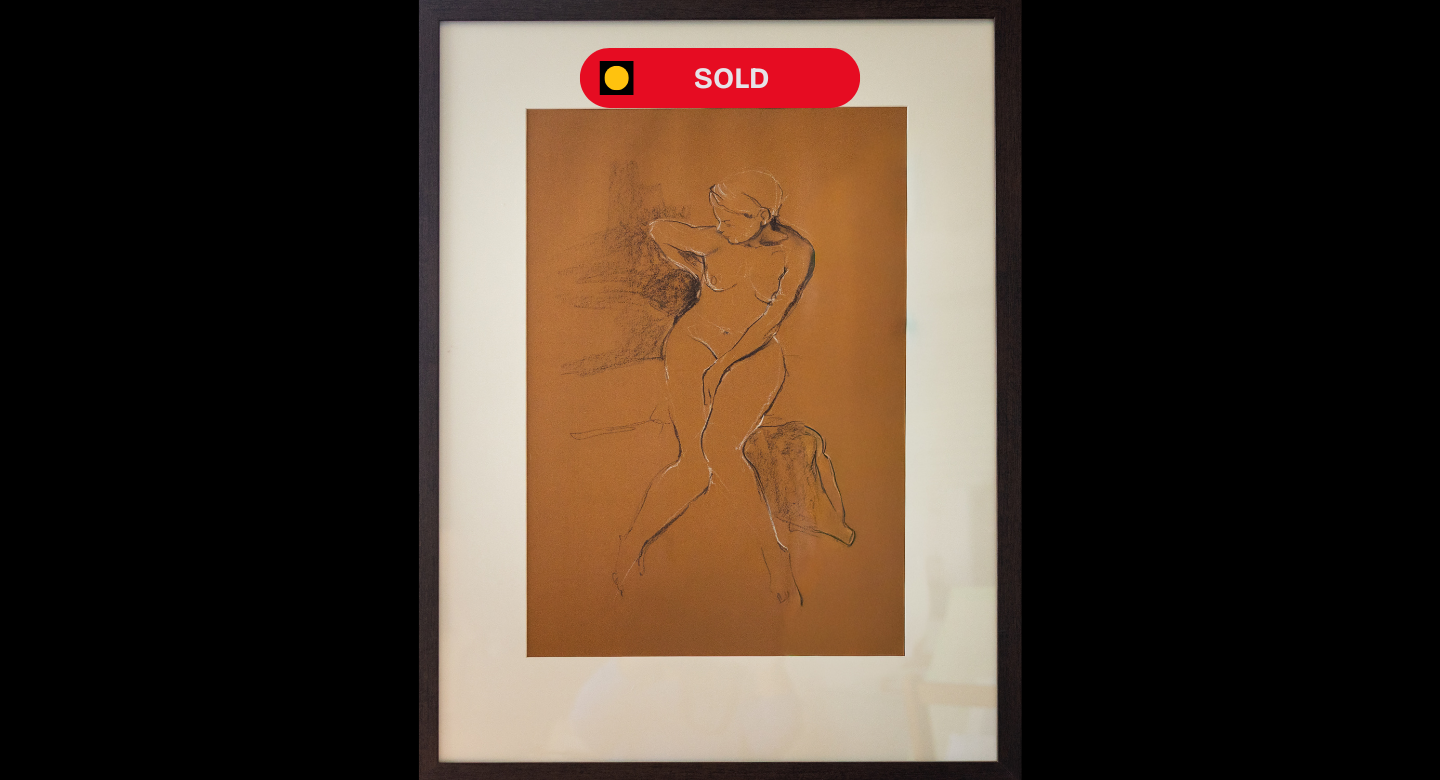

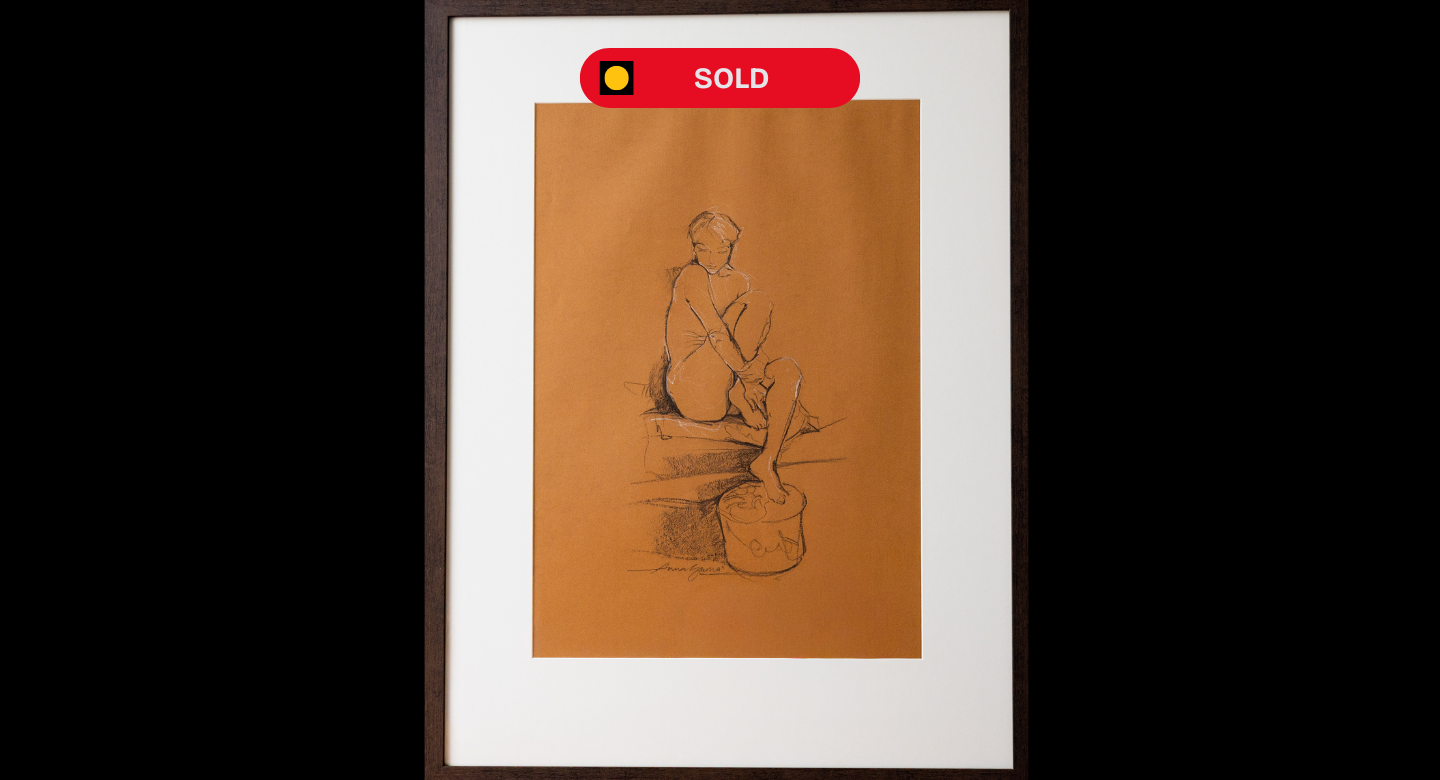

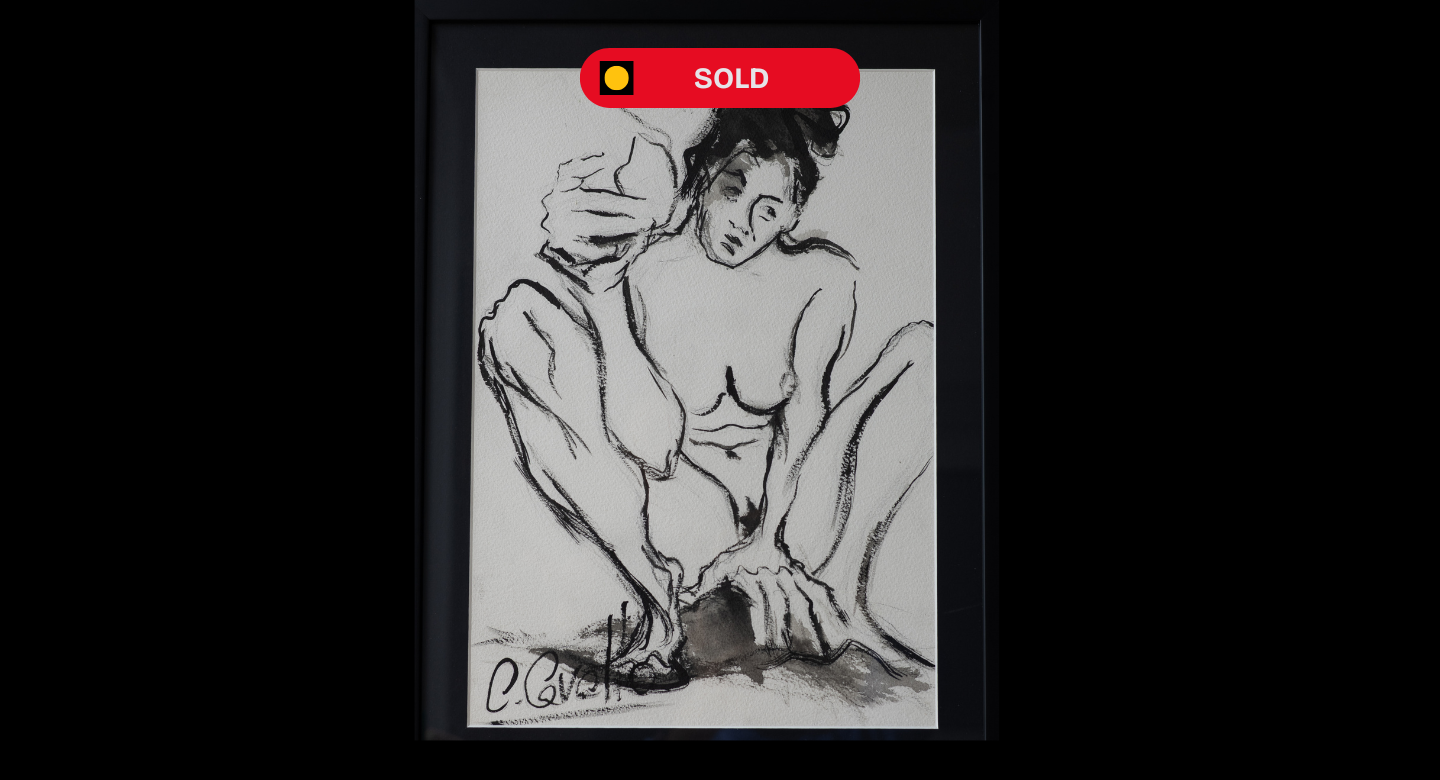

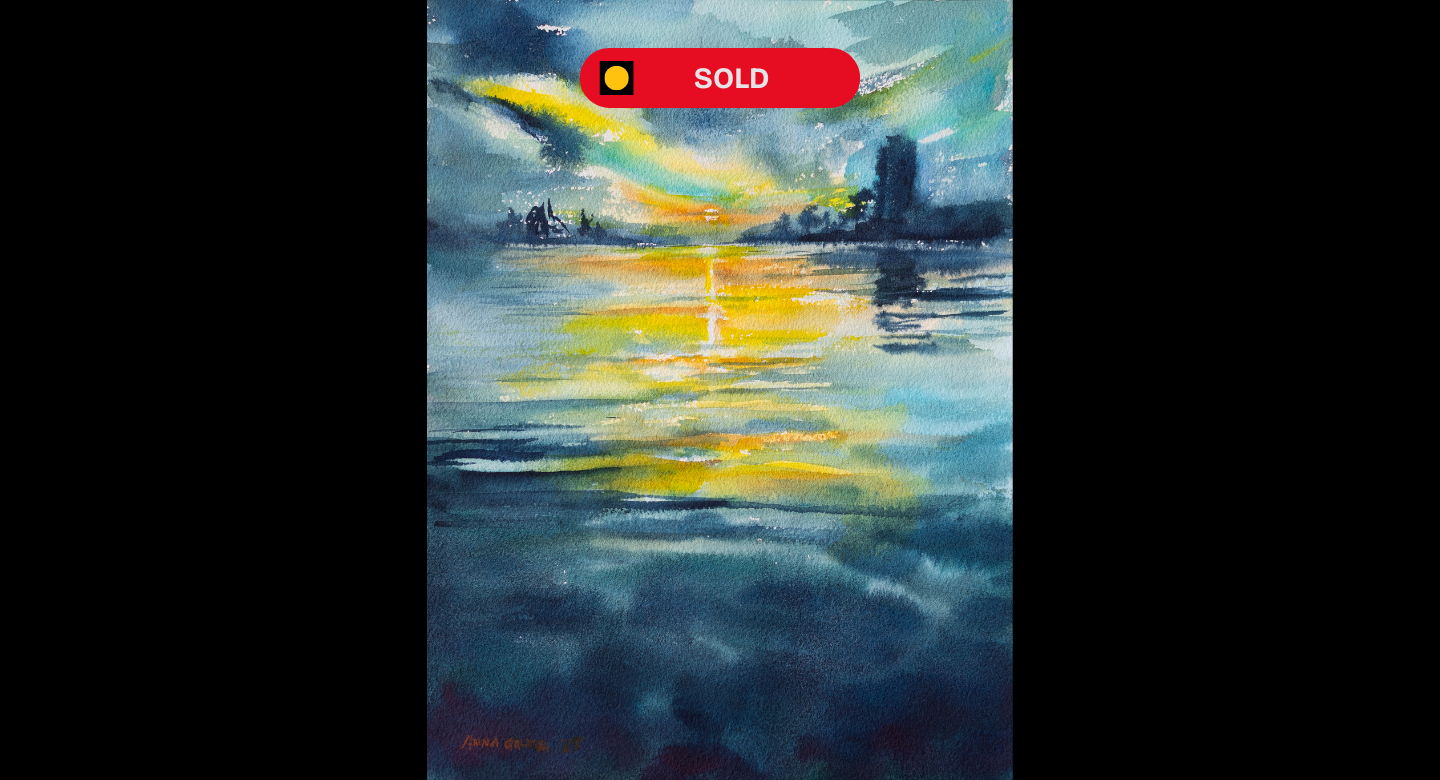

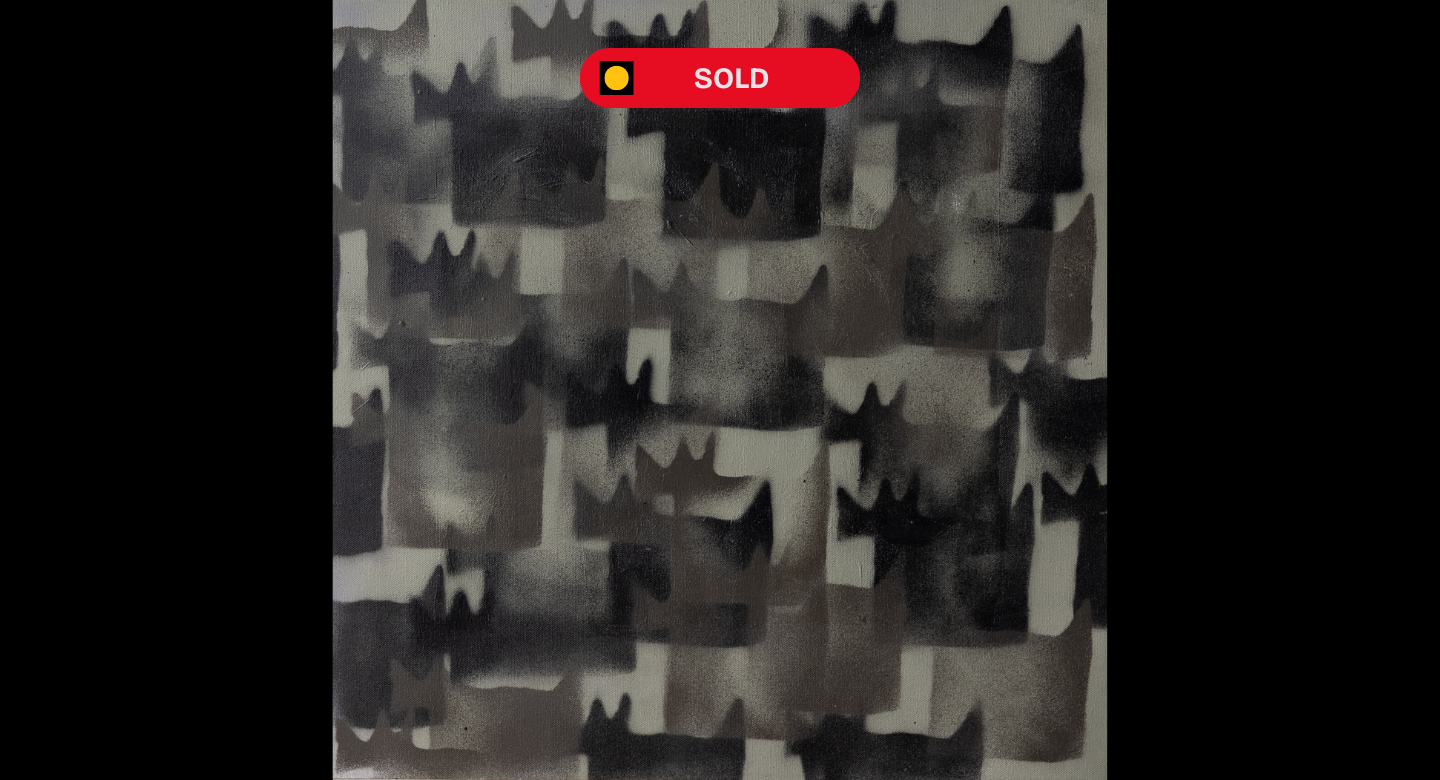

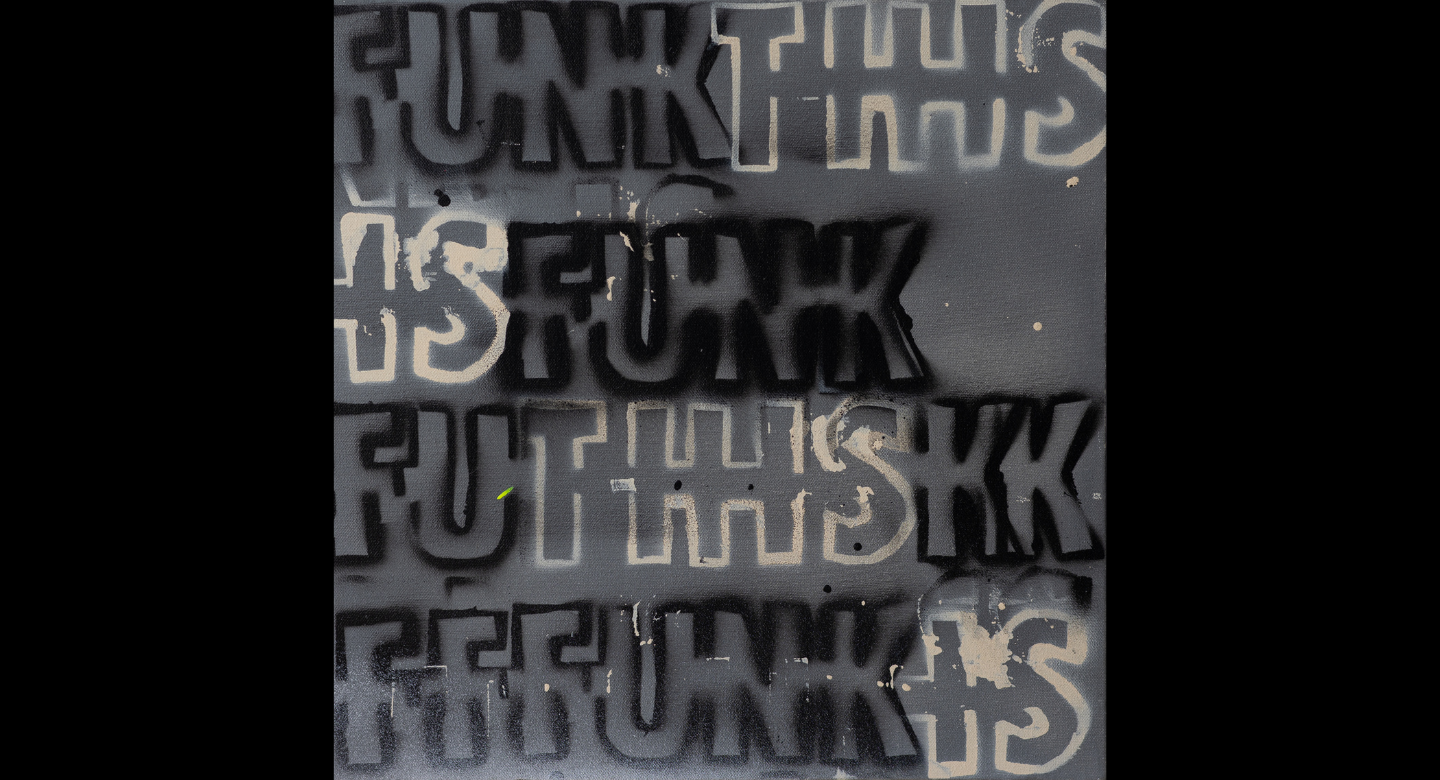

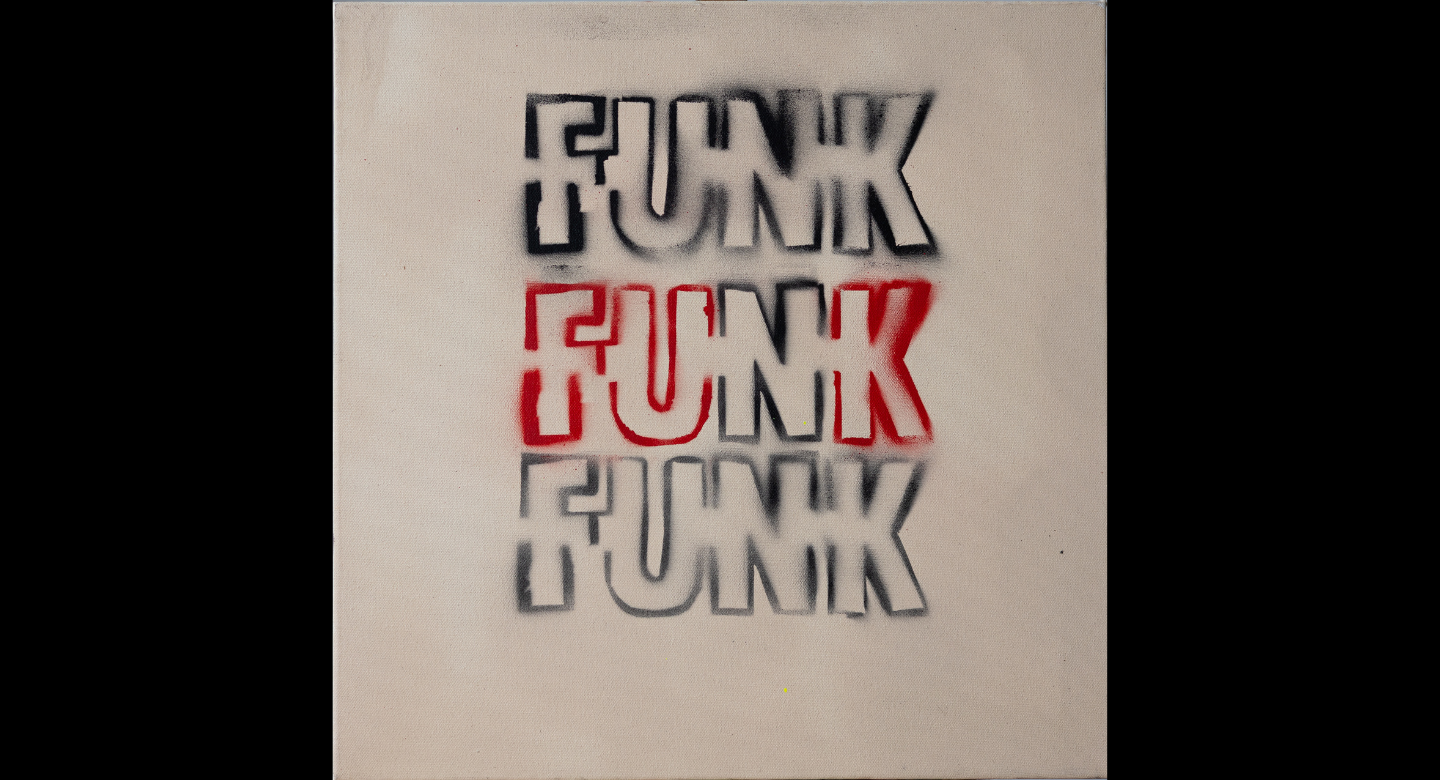

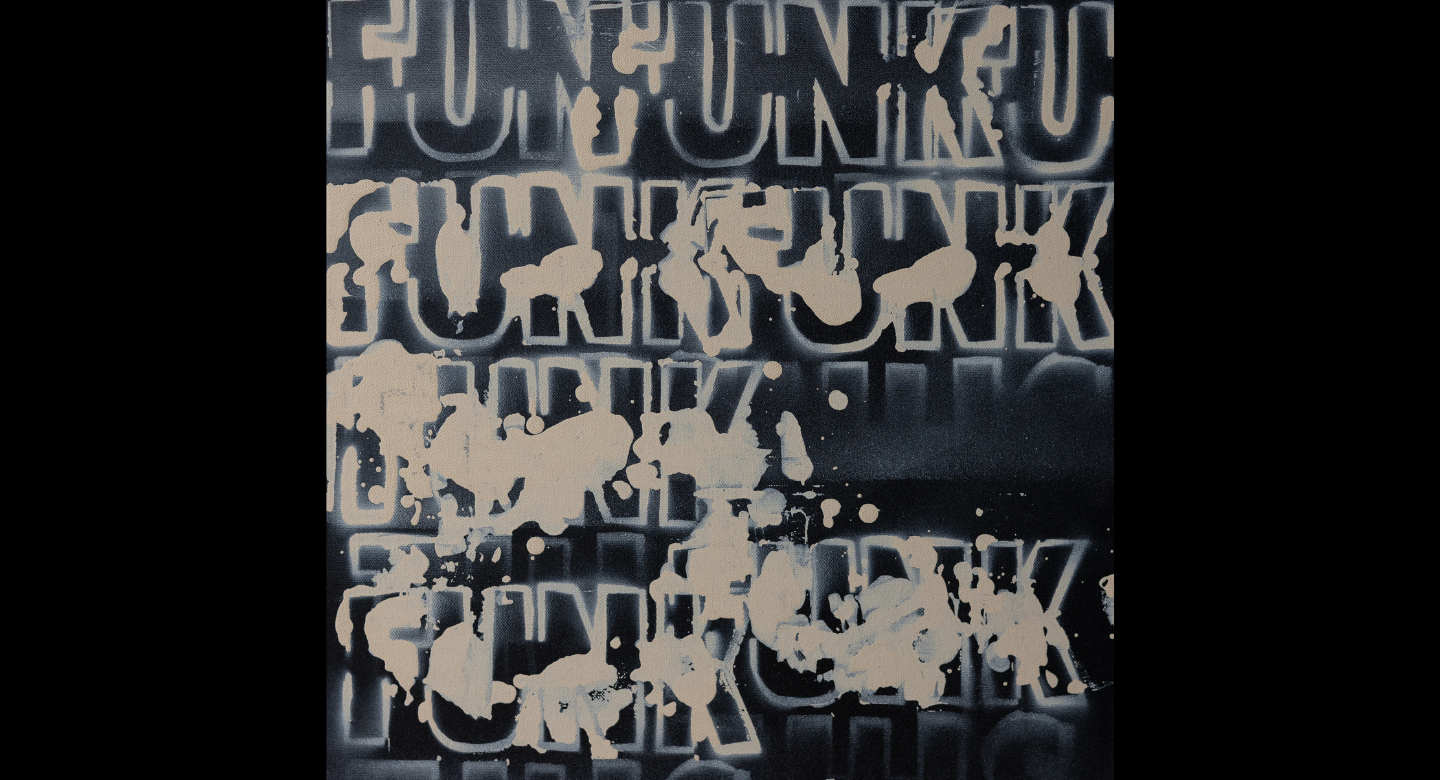

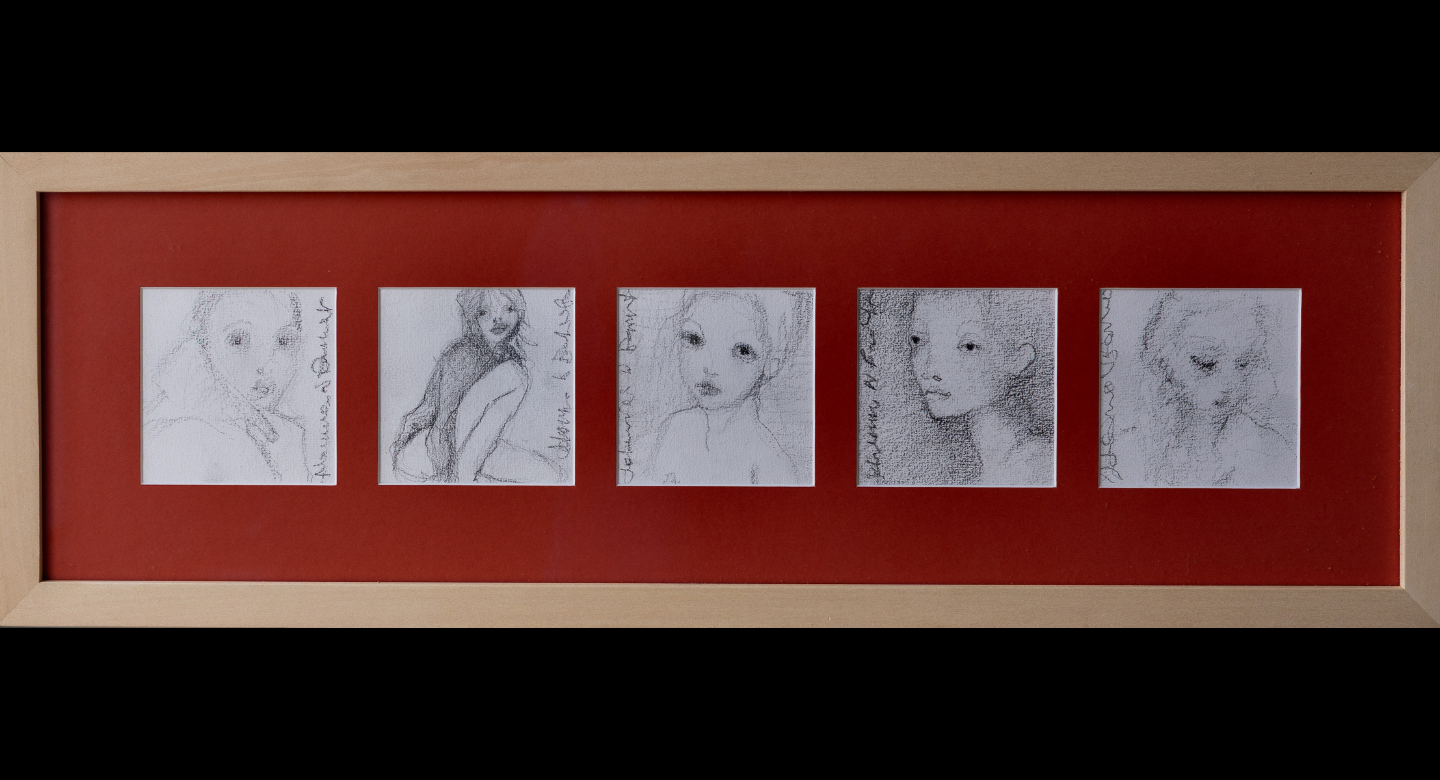

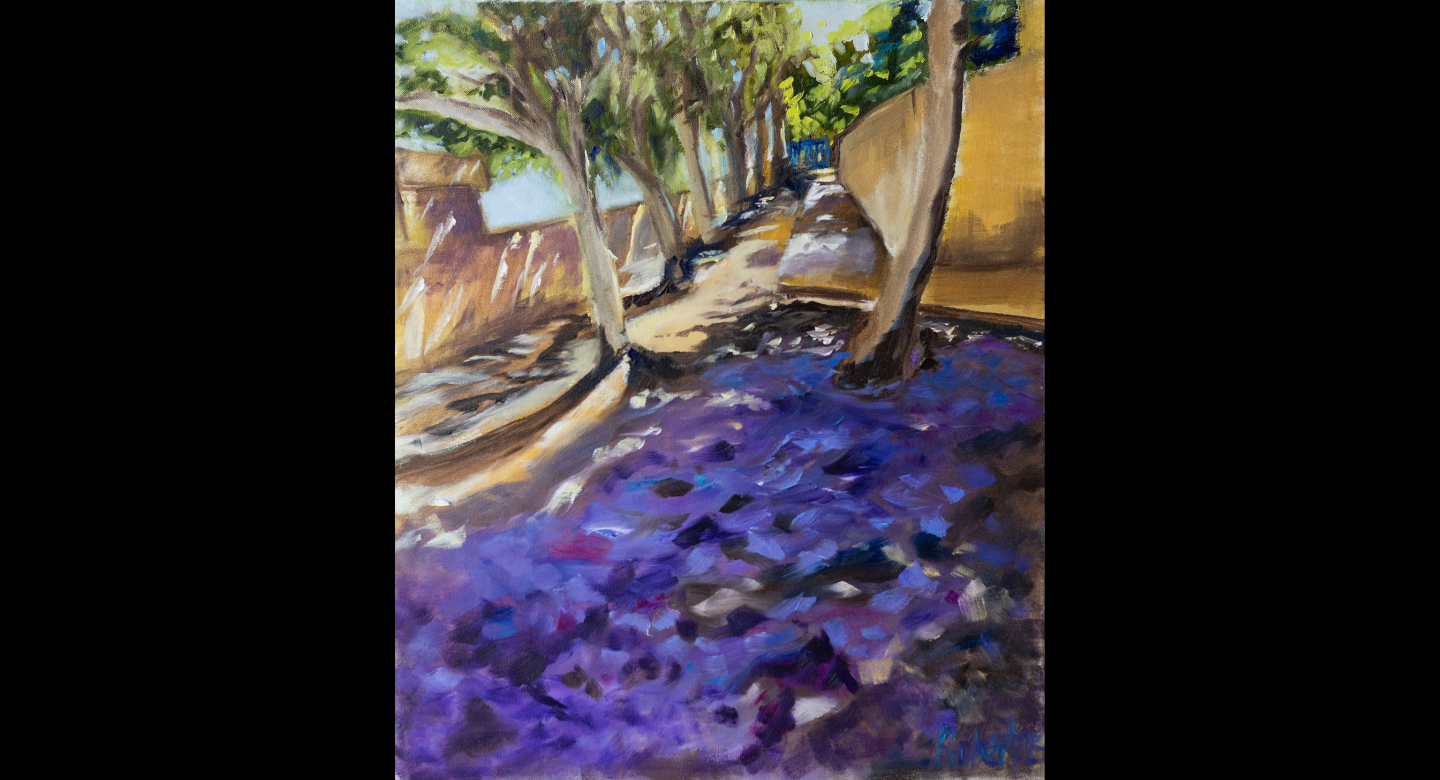

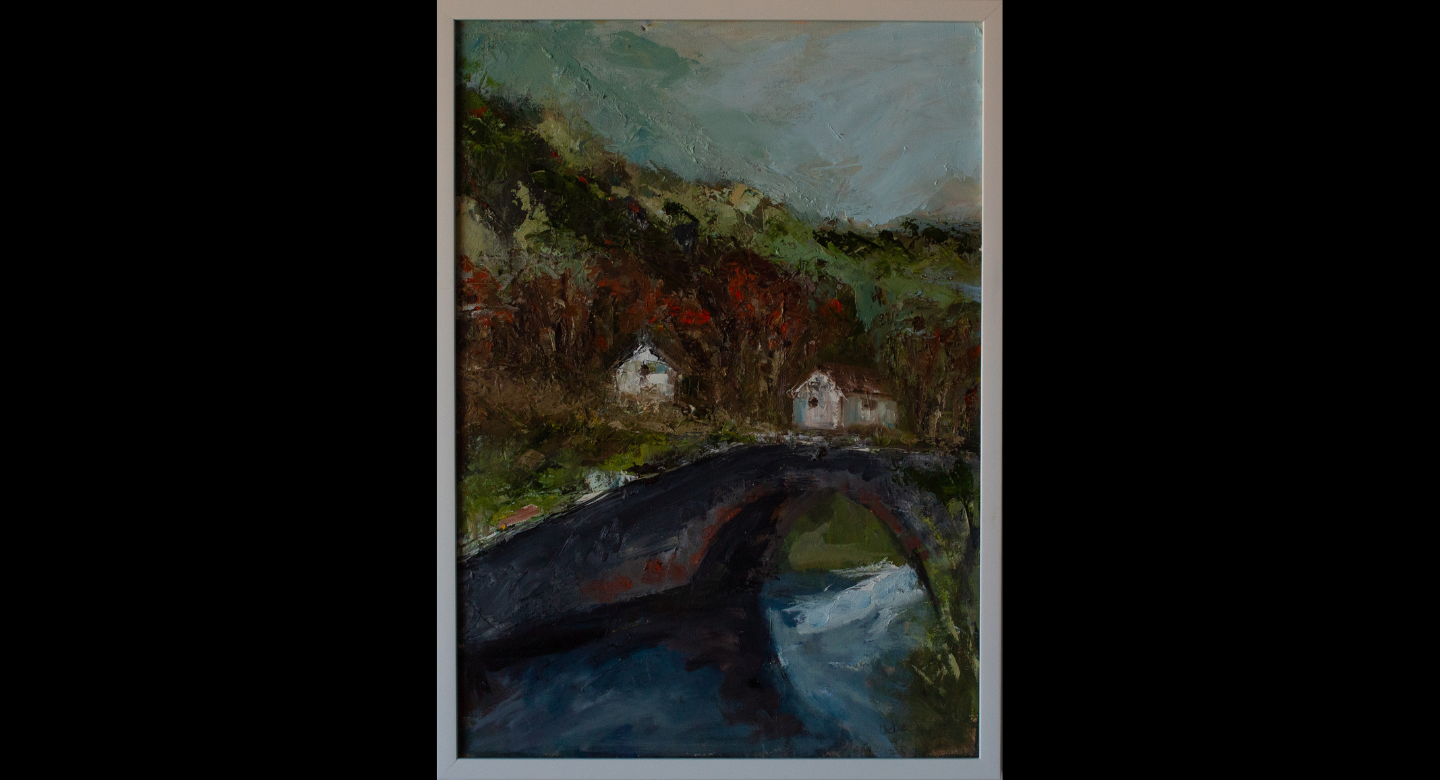

ART FOR THE SHIFT 2025

Top Stories

PL and PN end 2024 with heavy financial burdens and no donor transparency

Though their day-long telethons might have made you think otherwise, both the Labour Party and the Nationalist Party end..View More

Galdes, secret deals and a public company in ruins

Minister Roderick Galdes was tasked with responsibility for Malita Investments, a publicly listed, financially sound com..View More

Investors withdraw from MMH rescue talks as €15 million bond risk deepens

A third attempt to avert a potential default on €15 million in bonds issued by Mediterranean Maritime Hub (MMH) has co..View More

Minister failed to declare discounted penthouse in Cabinet asset declarations

Social Housing Minister Roderick Galdes is facing increasing pressure after it emerged that a penthouse he purchased at ..View More

Owen Bonnici retains aide who admitted to social benefits fraud

Culture Minister Owen Bonnici is employing in his private secretariat a political canvasser who has admitted in court to..View More

Dalli blocks information on Enemalta's missing €60 million

Energy Minister Miriam Dalli continues to block the release of information linked to a €60 million shortfall in carbon..View More