The newly-appointed Commissioner for Gender-Based and Domestic Violence, Audrey Friggieri, is set to find multiple realities that have become more complex since the law was enacted in May 2018.

Some of these complexities, which the courts and police and social workers have long grappled with, are indirectly emerging from court testimonies in the compilation of evidence of the spurned partner charged with the stabbing of Chantelle Chetchuti a month ago.

Those involved in an official capacity concede that, despite growing institutional efforts in the past year, the system failed Chetchuti. Despite warning signs – previous episodes of violence and alleged stalking – the tragedy was not averted.

Chantelle Chetchuti, 34 and mother of two, was stabbed multiple times in the head in Żabbar in February 2020.

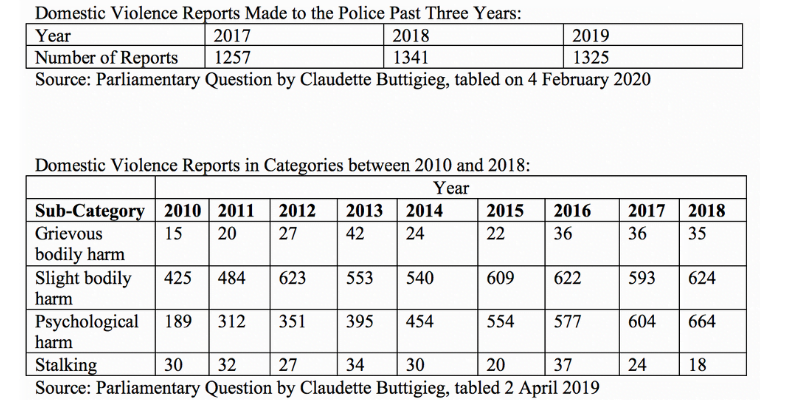

More widely, the nature of violence itself has shifted: the incidence of psychological violence has climbed steadily in recent years and has now become predominant over physical violence even while the overall figures have remained flat.

Other figures given in Parliament reveal that three out of four reports of domestic violence are made by women, and one fourth by men. Also, four out of five summary proceedings in court brought forward by the police fail.

The exact reasons for this high failure rate are not known, but Magistrate Ian Farrugia has recently lamented about the trend of alleged victims who opt to refrain from testifying against their spouse, leading to the collapse of the prosecution’s case. The magistrate said that this is extremely frustrating for the court and the police and a waste of time.

The situation is separately muddled by the apparent increase, according to lawyers, of false allegations in the buildup to – or in the midst of – marital separation proceedings in the Family Court. Most false allegations are made by women who proceed to accuse existing or former spouse of violence or abuse against themselves and children.

Although no statistics exist, lawyers say that false allegations are common. Separately, social workers estimate that around three in four allegations of abuse purportedly against women or children in the midst of litigation in the Family Court are spurious.

The phenomenon of false allegations has made the judiciary and the police wary and disbelieving. Many a father has been wrongly accused, spending many months condemned until proven innocent and his access to his children reduced to a couple of hours every week under the supervision of a social worker. (These false allegations do a disservice to real victims of domestic violence or abuse who have to contend with institutions that are wary of allegations being bandied out.)

It’s gotten even trickier with the increasing preponderance of psychological violence. With no outward signs, psychological violence is hard to prove or disprove, and even psychologists regularly get it wrong.

Passage of the Gender-Based Violence and Domestic Violence Act in May 2018 introduced the imposition of temporary protection orders and immediate eviction from the matrimonial home on the alleged perpetrator.

This was designed to empower victims, who wouldn’t have to remain under the same roof as the perpetrator in a situation of heightened volatility between the lodging of the report and the prosecution, which could take months. But in cases of false allegations, this measure led to a spate of wrongly accused men being thrown out of their home, only to be cleared many months later after much damage was done.

Following calls by magistrates and lawyers to amend the law – and a constitutional challenge by lawyer and MP Jason Azzopardi – changes made last July were designed to make more thorough verifications before imposing protection orders that led to evictions. Before last July’s amendments, the court issued protection orders on the basis of a risk assessment by social workers who, sources say, tended to err on the side of caution.

Now the investigations are tripartite: a risk assessment by the social worker drawn up after interviewing the victim or accuser, an investigative report by the police, and inquiries by the magistrate. The magistrate even interrogates the parties and visits the matrimonial home.

Legal time-terms have also been narrowed: the police are now obligated by law to prosecute, if it leads to that, within 30 days. The temporary protection order itself expires after 30 days unless renewed.

These legal changes have reportedly reduced the prevalence of false allegations, although false allegations of violence against spouse and children – and abuse on children – remain common in the Family Court. These are part of an overwhelming pattern of attritional family warfare that damages children and exacts an emotional toll on most judges who are typically reassigned after some years.

False allegations of violence or abuse in separation proceedings are made in pursuit of – or emotional fixation with – winning in court. You could gain the upper hand in a custody battle for the children if you drag the children in the alleged violence: it typically takes just an allegation or police report for the father to be put on an arrangement of seeing his children for a handful of hours every week under the supervision of a social worker. This allows the accusing party to make headway in the case and wear down the opponent.

There are also financial enticements: if the other party can be depicted as abusive or violent, or an adulterer, that could improve the chances of being granted a greater part of the assets on separation, as well as alimony payments. These alimony payments – typically only imposed by a court in the event of medical incapacity to work; or adultery, violence, or abuse; or abandonment of matrimonial home – on top of child maintenance payments, can amount to hundreds of euros every month.

Countries that have reduced the incidence of false allegations in the context of marital separation, as well as the incidence and ferocity of litigation, have tweaked the laws to inhibit the idea of winning. These include introducing the concept of shared parenting, making maintenance payments (if any) more formulaic and less variable, and doing away with provisions that assign or apportion blame and consequential division of assets of community of acquests (common property).

Another factor disinhibiting false allegations is the judiciary’s reluctance to hold accusers criminally liable for calumny or perjury, a reluctance arising from concerns that the children might suffer more. (It’s always the children who suffer most, as in the stabbing of Chetcuti last month – mother dead, father incarcerated, children orphaned and scarred for life.)

On the other hand, sources say that protection orders are sometimes ignored or circumvented, and this led to the harshening of the punishment for breaching protection orders last July – flouting the strict conditions of protection orders now incurs a fine of up €7,000 and/or imprisonment of up to two years.