The court today denied the Opposition Leader’s request to be given a copy of the findings of the Egrant inquiry, leading Adrian Delia to immediately announce he would be appealing the decision “with urgency”. The Shift analyses Judge Robert Mangion’s conclusions and the implications in terms of the public’s right to know regarding one of the most divisive cases in the country’s recent history.

The inquiry looks into whether there was evidence that the Prime Minister, or members of his family, or others who qualify as Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs), referring to John Dalli, Keith Schembri and Konrad Mizzi, could have been involved in corruption, money laundering or suspicious financial transactions from the accounts of PEPs in Azerbaijan through accounts held at Pilatus Bank – now defunct after its chairman was arrested in the US for evading sanctions.

The inquiry also looked into whether evidence existed that the Prime Minister’s wife, Michelle Muscat, was the Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO) of the third Panama company Egrant Inc revealed in the Panama Papers. Leaked emails had clearly shown the other two Panama companies belonged to government minister Konrad Mizzi and the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff Keith Schembri. The owner of the third company, Egrant Inc, was too sensitive to disclose by email. Assassinated journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia had reported it belonged to the Prime Minister’s wife.

Despite Joseph Muscat’s commitment to have the inquiry’s findings published in full, the evidence will remain under wraps following the court’s conclusion today.

The public interest

The court recognised the role of journalists and non governmental organisations (NGOs) to act as public watchdogs. It also acknowledged the Opposition’s role to act as a watchdog on the Executive (government) on issues of public interest and importance.

Judge Mangion pointed out that the Opposition has not only the right but also the duty to scrutinise the operations of government, saying this was one of the main functions of a Party in Opposition.

Yet, the court concluded that while the request made by the Opposition Leader satisfied the criteria of information in the public interest, the magisterial inquiry did not qualify as information that could be requested “by right” (bi dritt).

While the public has the right to access information held by the authorities, this did not apply to documents held by the Attorney General (AG) who is in fact exempted under the Freedom of Information Act. The court noted that none of the previous court judgments cited by the applicant was related to any cases involving a magisterial inquiry.

The court also noted that since it was the AG that published the conclusions of the inquiry, then the public interest criteria had been met. “Regardless of any public interest in its contents, a proces verbal (the findings of the inquiry) is still a judicial act even once it is handed over to the AG”.

Delia has argued that if the information being requested should be made available to the public as “a right” then there would not have been any need for a request to be made to the court for its publication. He has stated that the fact that the information was made available to the Prime Minister and not to the Opposition Leader has put him at a political disadvantage.

Police investigations

The court noted that while the inquiry was concluded, police investigations related to the findings remain ongoing. “The Police Commissioner confirmed that he was given a copy by the AG’s office and that there were three police Inspectors and their teams that are still pursuing investigations on the findings”.

Judge Mangion also noted that, so far, no individuals have been charged on any findings contained in the inquiry. Yet it maintained the evidence had value as part of a probe and there was no ‘right’ according to the law for individuals to have access to this evidence.

The aim of the inquiry was for the evidence collected and preserved by the inquiry to be used for eventual prosecution, the court noted, leading to the conclusion that the AG’s refusal to hand over the findings to the applicant (Delia) did not amount to a breach of the right of freedom of expression.

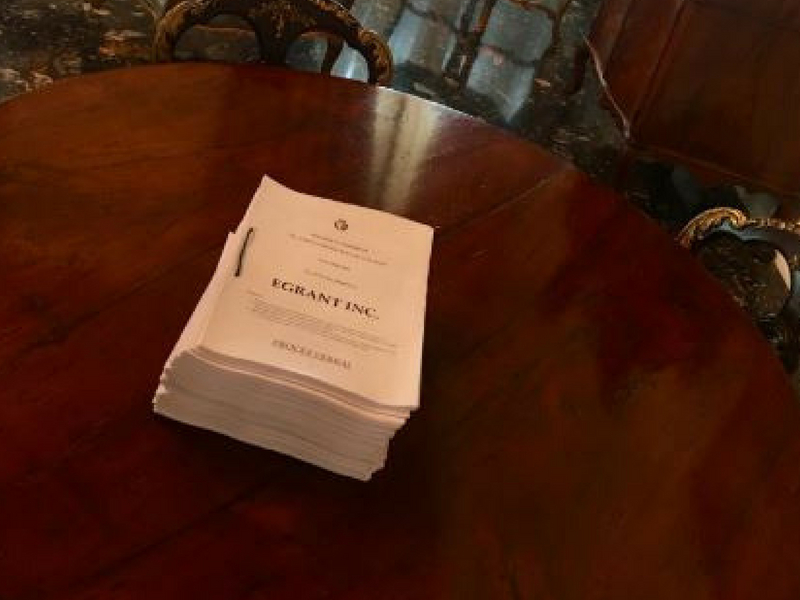

The AG argued that the entire findings amounted to more than the 1,500 pages given to the Prime Minister. It contained a number of additional documents and evidence to sustain the findings. The AG insisted that what the Opposition Leader was requesting went beyond what the Prime Minister received.

Delia is arguing that it is not only the AG that has a copy of the Egrant inquiry findings. It has been established that the Office of the Prime Minister, the Justice Ministry, the Police Commissioner and Joseph and Michelle Muscat’s lawyers also have a copy.

The full Egrant inquiry shown on Twitter by Prime Minister’s Head of Communications Kurt Farrugia.

No discrimination

The AG also argued that the Opposition Leader failed to identify the grounds on which he claimed discrimination. For discrimination to be proven, the applicant had to prove that he was treated differently to others in a similar situation and that the action was unjustified.

On this, the court concluded that the applicant failed to prove that any right had been breached on the basis of discrimination and that the applicant did not put forward any claim of a further breach of rights outlined in the European Convention on Human Rights.

The court also noted that it was abundantly clear that the Prime Minister’s situation and that of the applicant were different in the context being assessed. “The applicant himself admitted that if the Prime Minister had not been given a copy, then he would not have had the right to request it”.

It noted that it was the Prime Minister who had requested the inquiry and that he had tied his authority to continue in this role with the inquiry’s findings. “In no way was the Opposition Leader’s situation the same as that of the Prime Minister,” the court ruled.

Delia said the Opposition had the duty to pursue this information in the public interest, insisting on the public’s right to know. “We shall appeal to the Constitutional Court asking that the full report be made public. People have a right to know,” Delia said.

Court recognizes Opposition as public watchdog, the nature of info requested as of public importance & interest but deems #Egrant report doesn’t qualify automatically. We shall appeal to the constitutional court asking that full report be made public. People have a right to know

— Adrian Delia (@adriandeliapn) May 14, 2019

He insisted that Muscat has always said he wanted the Egrant inquiry to be published in full, questioning his reluctance to fulfil this promise.

Former PN Leader and MP Simon Busuttil, who led the charge for an inquiry on Egrant, also reacted saying it was time for the Prime Minister “to stop playing the Egrant victim card”.

“It’s not like owning a Panama company is wrong for him. If it was, he would have long fired his closest Cabinet members and left with them. Just publish the report and let the people decide,” Busuttil said on social media.

Setting the record straight

The Maltese government has aggressively marketed the summary of the inquiry as an unconditional cleansing of the slate. This is not accurate.

An inquiry is not a conclusive judgment, ruling or result of some independent inquiry that can conclude on guilt or otherwise. In fact, the magistrate is not allowed to decide or state whether a person is guilty or otherwise (and the magistrate did not).

The Egrant inquiry was what is known as an inquiry into the ‘in genere’ or material evidence of a crime. Its aim is for the magistrate (not a court) on duty at the time (in this case Magistrate Bugeja at the time, now Judge in a controversial appointment) to proceed to preserve any evidence of a possible crime.

The end result of an inquiry is typically a lengthy document which is a record of the evidence collected.

This could, in turn, be used for further investigation by the AG and the police, if there is enough evidence (or willingness) to commence proceedings in court – the only place where guilt or absolution may be awarded – in which case the findings of the inquiry is filed as evidence.

It is also worth bearing in mind that the investigation of offences is, and remains, the responsibility of the police. In fact, the court points out today that while the police claim that investigations continue, no further action has been taken.

It is also important to keep in mind that the terms of reference of the Egrant inquiry were determined by Muscat’s lawyers and they were limited in scope.

This limitation in scope is important since the summary does include clues (such as Keith Schembri receiving payments from Brian Tonna’s Willerby Inc) in relation to matters that, while not included in the strict terms of reference of the Egrant inquiry, are relevant to the other inquiries.

Despite the fact that two years have passed since these were requested, there has been no indication of the progress on the other inquiries involving the Prime Minister’s chief of Staff, Keith Schembri.