Having failed to silence their most vocal critic, Russian authorities are going to great lengths to discredit Alexei Navalny.

On 23 January, tens of thousands of Russians defied their government’s warnings and took to the streets in more than 100 cities to protest Navalny’s arrest and imprisonment. He is a harsh critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin and his government’s corruption.

The Russian authorities responded in two ways: on the streets, Russian police heavy-handedly broke up the rallies and detained thousands of individuals; in the media, authorities deployed their disinformation campaign, this time aimed squarely at discrediting Navalny and the protesters.

This is some pretty pathetic stuff. Putin is desperate to create the impression that Russian people love him after 90 million Russians have watched the Navalny video about his $1.5 billion palace https://t.co/ASoqefBx7V

— Bill Browder (@Billbrowder) January 29, 2021

Governments around the world have a plethora of tools at their disposal for stifling dissent. Nevertheless, discrediting your opponents by insulting them, remains one of the simplest yet most effective ways of undermining their argument.

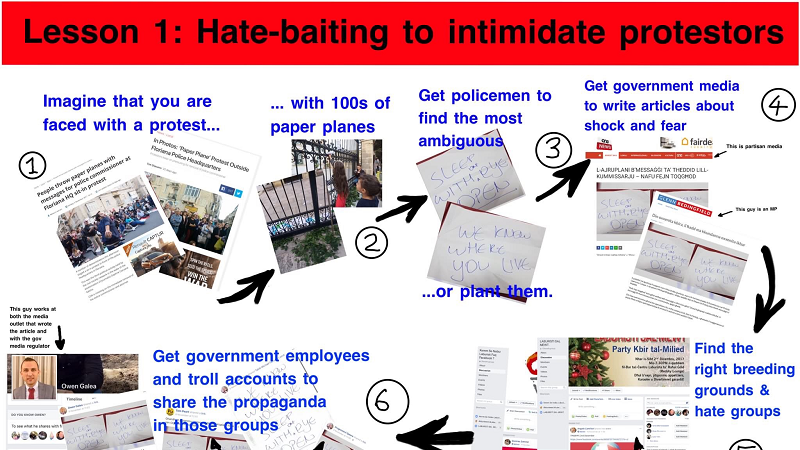

It has become so pervasive in everyday discourse that we barely notice it anymore, even when it happens to us. Some of the disinformation tactics used against Navalny have been used to discredit activists and journalists in Malta.

A problem that will not go away

Navalny, a corporate lawyer, has been involved in Russian politics and activism all his adult life. He rose to prominence in 2007 when he launched the anti-corruption campaign which would become his signature issue.

As his popularity grew, Russian authorities seemed unable to undermine him. Navalny was not reliant on State media for publicity thanks to his blog, which he used to expose government corruption. Neither was he involved in big business, so he has no dubious wealth with which to discredit him. And he refuses to be driven into exile, as the latest events have clearly shown.

In 2014, Navalny and his brother Oleg were convicted on trumped-up fraud charges. Navalny was given a suspended sentence, but his brother, a former postal service employee with no political involvement, was sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

On 20 August last year, Navalny fell ill when returning to Moscow from the Siberian city of Tomsk. He was flown to Germany for treatment two days later. The German doctors published the clinical details on how they treated him for Novichok poisoning, a deadly nerve agent.

Navalny claimed that the Russian government was behind the attack even though the authorities continue to deny any involvement.

While Navalny spent his time in Germany working with investigative journalists to find out who was behind the attack on him, the Kremlin worked on dissuading him from returning home.

In late 2020, the authorities put Navalny on Russia’s federal wanted list arguing that Navalny broke the terms of his probation from the 2014 conviction. Nonetheless, Navalny returned to Moscow, where he was promptly detained.

Shortly after his arrest, Navalny’s team released a video investigation that claims President Putin spent illicit funds on an extravagant palace complex on the Black Sea. Within a day of its publication, it had more than 22 million views.

Widespread discrediting campaign

The Pro-Kremlin media campaign to discredit Navalny has been underway for some time. Among some of the more fantastical claims are the narratives that he was not poisoned in Russia but in Germany, that his medical condition is a result of chronic disease, that he was poisoned by a friend and that Navalny himself could have been responsible for his coma.

When Navalny released the recording of a call in which he tricked a Federal Security Services (FSB) officer into revealing details of the alleged poisoning plot, a Kremlin spokesperson responded by stating that Navalny had a “persecution complex” and that he was “comparing himself to Jesus”.

Via the @AvtozakLIVE telegram channel, it’s getting increasingly brutal out there pic.twitter.com/YsDbyFzXTP

— Ilya Lozovsky (@ichbinilya) January 23, 2021

During the 23 January protests, when footage emerged of a young boy being yanked from the crowd by a police officer towards a riot van, pro-government media started reiterating claims that Navalny was brainwashing children to maximise protest turnout.

These claims were echoed by government officials and by President Putin himself. When asked about the latest protests in a virtual meeting with Russian students on 25 January, he focused on the same topic. “It’s absolutely unacceptable to thrust minors forward,” Putin said. “After all, that’s what terrorists do.”

The simplest form of disinformation

Attempts at discrediting opposition are not a novel or creative way of sowing doubt, nor is it an exclusively Russian tactic for that matter. All one has to do is think of disgraced former US President Donald Trump and the number of individuals he routinely insulted.

“Discrediting” in this context is using false claims or the logical fallacy better known as the argumentum ad hominem (to the man) or personal attack. It takes place in the political arena as much as it does in academia, in the media, in the courtroom and in everyday confrontations.

Personal attack arguments are easy to put forward as accusations, are often difficult to refute, and can have an extremely powerful effect on persuading an audience. What’s more, placing the focus on the person instead of the person’s argument, distracts from the issues that matter.

In the so-called abusive ad hominem tactic, someone argues that because a person has a bad character, we should not accept that person’s claims.

Simply consider the coordinated vilification and dehumanisation campaign throughout most of Daphne Caruana Galizia’s career and the way these campaigns tried to undermine her investigative work. Labelling the opposition as “traitors” is another common example.

Another dishonest form of the ad hominem argument is the tu quoque, or “you, too” version, which is an attempt to discredit a person’s claims because the person has failed to follow his or her own advice. It is a favourite among our politicians.

There is also the “poisoning the well” type of ad hominem attack, in which the character assault is launched before the listener has had a chance to form his or her own opinion on a subject. A good example of this is the narrative that is aimed at discrediting the public inquiry on Caruana Galizia’s assassination.

Attacking the nature of the public inquiry is similar to attacking a person’s character. By repeatedly saying that the inquiry is biased against the government, that it is partisan and that it is a “waste of time” you are influencing your audience before they have had the chance to make up their mind on the proceedings.

Are the attacks ever fair?

Some argue that when the claims made about a person’s character or actions are relevant to the conclusions being drawn, then they are fair.

Take Minister for Transport and Infrastructure Ian Borg, for example. When Borg claimed he was unaware that a man from whom he had acquired land for a pittance was mentally ill, the court did not believe him. He has been caught being parsimonious with the truth on numerous occasions, including about works that fall within his portfolio.

His behaviour clearly jeopardises public perception of his ability to do a good and honest job. The criticism levelled towards him is warranted, even if nothing seems to come of it.

Being able to tell when an ad hominem attack is fair and when it is merely an insult aimed at undermining a legitimate argument, can help us evaluate which instances of its use we should ignore and which we should consider.

In the case of politicians, it helps us ask how relevant their character or action is to their ability to perform in office. A question that is too often overlooked.

Why do you care about a right-wing nationalist Russian, when a real hero Julian Assange rots in a UK prison without charge?

Where is the great human rights campaigner Bill Browder and why isn’t he calling for the US and UK to be sanctioned for the mistreatment and torture of Assange?

Tell me, if a US citizen was taking money from Russian government sources, to create elaborate smear campaigns against US politicians and public figures, do you think they might be in solitary confinement, faster than you can say Chelsea Manning?

Defending the human rights of one person does not necessarily deny rights to another. If you bother to search, you can see we have covered Julian Assange’s case. Instead, I question your stand about those who should be dismissed because they don’t fit your view of the world.