Malta’s progress in implementing the recommendations by anti-corruption body GRECO on the judiciary and members of parliament has not impressed civil society group Repubblika as it pointed out that the government was still clutching onto its control of high ranking political appointments.

The Shift turned to Repubblika for their reaction after the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption body published its annual report, giving a statistical overview of the progress Malta made in implementing recommendations from its fourth round of evaluation on corruption prevention about MPs, judges and prosecutors.

“The implementation score for the fourth report is therefore distinctly unimpressive given that what has been left undone has been superseded by a fresh set of recommendations,” Repubblika told The Shift.

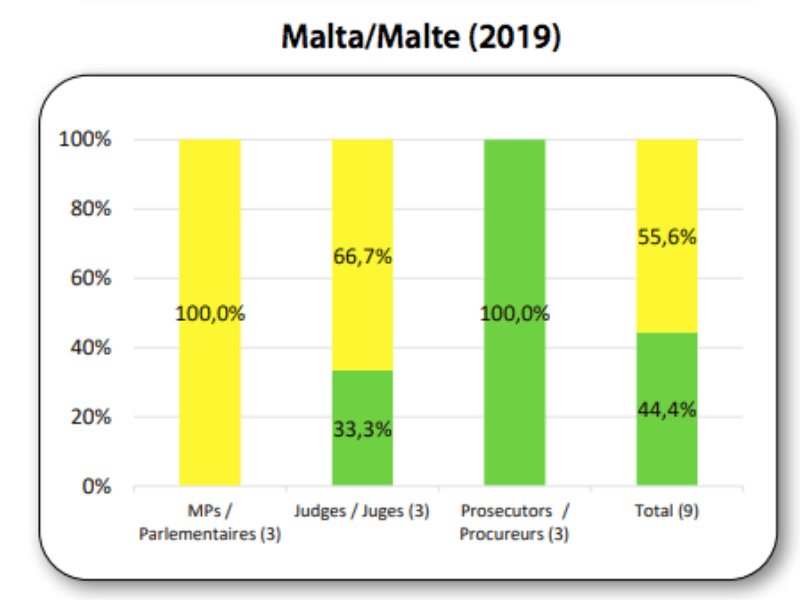

At first glance, the report reveals that 55.6% of the GRECO recommendations were partly implemented, while 44.4% were implemented.

GRECO said Malta “implemented satisfactorily or dealt with in a satisfactory manner four of the nine recommendations” contained in the report.

Statistics for Malta’s recommendation implementation of the fourth assessment. Source: GRECO

Repubblika pointed out that in its fifth evaluation report, GRECO said: “Malta lacks an overall strategy and coherent risk-based approach when it comes to integrity standards for government officials”.

“That is still the case. And that’s by design,” Repubblika said.

The fifth report, which dealt with corruption prevention about central governments and law enforcement agencies, called on the Maltese authorities to implement important reforms in the justice system and to crack down on corruption and nepotism, among other issues.

The lack of action was also criticised by Special Rapporteur Pieter Omtzigt who called out the government for not making progress on implementing the 23 recommendations in the fifth round assessments published in April 2019.

Repubblika noted that, with regards to MPs, GRECO highlighted the need for enforcement and regulation on declarations of assets, as well as setting standards of ethics, through a range of sanctions.

It welcomed the adoption of the Act on Standards in Public Life, as well as the appointment of the Commissioner for Public Standards.

“But checking parliamentarians for corruption in the Maltese context is not addressing the real problem of corruption. There’s not much point in bribing a backbench MP or the Speaker. Our Parliament is a dud and rubber stamp for the government so there is no autonomous decision-making power that can have any real material impact on people’s lives,” it said.

Instead, the real problem lies with the authorities reluctant to implement measures that would limit or restrain the prime minister’s power to reward their friends with patronage, influence or guaranteeing their impunity.

“The real cesspits of corruption are within the government, the police, the administration, public procurement, planning and regulatory authorities and the judiciary, where a bribe, conflicts of interest, political interference and the excessive discretionary powers of our prime minister can make a difference to people,” Repubblika said.

Corrupting the right persons could get a case shelved by the police or the prosecutor, an illegal development sanctioned, “laundered money ignored, your public works contract bid accepted and so on,” it added.

The government was dragging its feet on renouncing its control on appointments to the judiciary. “The police commissioner and the chief prosecutor remain the direct choice of the prime minister, and the police remain unwilling or unable to investigate corruption, let alone prosecute it,” Repubblika said.

The police ignored reports by the Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit about politicians laundering money and magisterial inquiries into bribery and corruption were still open three years down the line.

The so-called Permanent Commission Against Corruption remained permanently unable to conclude even one case against any public official, the organisation added.

The negative effect of a country’s lack of action was highlighted by GRECO president Marin Mrcela in the report as he pointed out that the failure to address shortcomings in fighting corruption identified by GRECO left the country’s system flawed.

“When we issue our recommendations, we do so because not addressing the shortcomings we identify leaves the system flawed. Our Member States should not await the next big scandal to make reforms. Instead, the best course of action is to proactively implement GRECO recommendations. This will, in turn, create the necessary conditions for corruption to be prevented before it is too late,” Mrcela said.

People’s growing expectations on exemplary conduct by persons in public office have increasingly been disappointed and the mass demonstrations held in Europe in 2019 “calling for justice and holding public office holders to account” confirmed this, according to GRECO.

“Politicians, irrespective of their political affiliation, need to lead by example as it is exemplarity which is expected from them. After all, politicians are meant to serve, not to rule, the people,” he added.

Mrcela pointed out that GRECO was witnessing corruption or unethical behaviour by such persons in “too many countries”. This lowered trust in and respect for such institutions which, in turn, “erodes democracy, human rights and the rule of law”.