The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission – officially known as the European Commission for Democracy through Law – issued an authoritative report a year ago that recommended fixes to structural weaknesses in Malta’s rule-of-law.

At the time, Justice Minister Owen Bonnici had told the Venice Commission that the government would implement all the reforms, a vow repeated by the Prime Minister a few days later.

A year on, only one of the recommendations was rolled out in half-measure, a move that legal scholar Kevin Aquilina characterised as being “in bad faith”. The Special Rapporteur of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, Pieter Omtzigt, criticised for “falling short of Venice Commission requirements.”

The structural weaknesses – and the stability of the edifice of the State itself – has become increasingly unsteady under the pressure of the revelations of the Daphne Caruana Galizia murder inquiry in the past few weeks. Aquilina wrote last week that the country has now descended into an “unprecedented constitutional crisis”.

As proceedings over impingements on judicial independence commence at the European Court of Justice, and a debate in the European Parliament is expected to discuss initiating sanctions procedure on Malta next week, this is a guide to the main Venice Commission recommendations and the state of play one year on.

Judicial independence

The primary focus of the Venice Commission was on bolstering judicial independence through the system of judicial appointment and removal. The Commission said the Prime Minister’s discretion in making appointments “falls short of ensuring judicial independence”.

The Commission then recommended a system that is the norm in much of Europe: that magistrates and judges are selected by an autonomous organ in which at least half of its members are drawn from the judiciary, and that appointment follows the issuance of calls for expression to fill specific vacant roles within the judiciary. Then, selected candidates for specific judicial office are recommended directly to the President for appointment, who would be bound to make these appointments.

This is part of a holistic reform in which the Commission recommended expanding the President’s Constitutional role to make the presidency balance the Prime Minister’s current excessive powers.

Last April, instead of carrying out the recommended reform, the government made the largest complement of judicial appointments in a generation, changing more than 10% of the judiciary in one fell swoop.

This triggered a constitutional lawsuit by NGO Repubblika challenging the six appointees, as well as the wider system of appointments, under provisions of various constitutional laws. The challenge led to a groundbreaking decree that coupled a specific provision of the Maltese Constitution with fundamental tenets of EU law, laying the ground for popular court actions against laws that are at odds with EU law.

The Repubblika case itself has now escalated to the European Court of Justice under the so-called preliminary reference procedure, in which the ECJ will guide Malta’s constitutional court in its judgment. The ECJ is expected to say that the Prime Minister’s power of judicial appointment impinges on judicial independence.

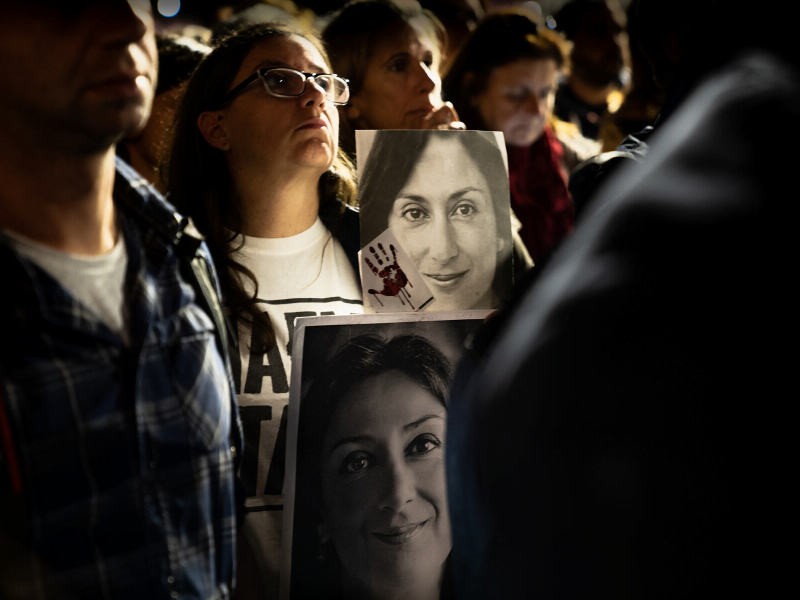

Helene Asciak, sister of assassinated journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia among the crowd of protestors demanding Joseph Muscat’s resignation. Photo: Pierre Ellul.

Separating roles of Attorney General

The Commission’s recommendation to separate the prosecutorial role of the Attorney General from his role as the government’s advisor-at-large and defender in lawsuits against the State has long been accepted as a necessity in Malta.

The Justice Minister piloted a law to separate these roles last spring. Yet the law was severely criticised for falling short of the Commission’s recommendations, particularly in two important respects: under the new law the Prime Minister still retains final discretion in appointing both the Attorney General and the State Advocate, and no provision was put into the law that would allow victims of crime to challenge the AG in court if he fails to forge ahead with prosecutions.

The latter is significant because, in the event of crimes punishable by more than 12 years’ imprisonment, there is no possibility of the victim or victims requesting judicial review of the AG’s discretion on whether to prosecute or not.

This could be potentially contentious in serious crimes by politicians, such as money laundering, in which the AG retains an opaque and unchallengeable discretion.

Constitutional Court’s power to nullify laws

Former European Court of Human Rights Judge Giovanni Bonello has said that Malta is the only democratic country in which a law deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court remains in force unless parliament repeals it.

The Venice Commission addressed this aberration by recommending putting in place provisions that would lead to the nullification of any law struck down by the Constitutional Court.

A year on, we remain in the bizarre situation in which a law judged unconstitutional would lose its compulsion or effect only in the immediate case challenging it in court, but remains in force in all other similar cases.

This is best illustrated by the string of lawsuits challenging old rent laws – the Constitutional Court has taken to declaring the law’s provisions unconstitutional in case after case, yet anyone affected has to take the battle to the Constitutional Court anew to get a ruling in his or her case.

This carousel of lawsuits has been denounced by Bonello for being “an immense waste of resources and expenses.”

The Maltese flag flies high in a protest in front of parliament on 26 November. Photo: Caroline Muscat

Separate the legislative from the executive

In a bid to make MPs more independent-minded, the Commission recommended making MPs full-time, increasing their salary and staff to enable them to delve more professionally into parliamentary work, and also set up a Council of State that would advise parliament on compatibility of Bills with EU law and human rights provisions.

These recommendations were made in a context in which MPs from the government side, as well as most opposition MPs, have all been engaged in government roles – whether as ministers or to serve on Boards or other organs of the State – and that this buys their reticence or loyalty in parliament.

Parliamentary Standards Commissioner George Hyzler took up this call in a strident report.

In a riposte, the Office of the Prime Minister adopted a narrow interpretation of civil law to argue that this practice was not illegal. Hyzler and Aquilina have separately insisted the practice goes against the spirit of the Constitution.

MPs’ abdication of their democratic role of scrutiny of the executive arm of government has been laid bare in the current crisis. Labour’s MPs first met privately in the PM’s country retreat to confer blanket support to any decision the PM might take, and then a week later parliament went on a five-week break.

Expanding role of Ombudsman and Permanent Secretaries

After lamenting that the Ombudsman’s reports are often ignored, the Commission recommended that the powers of the Ombudsman are entrenched in the Constitution and expanded, and include an obligation for parliament to debate his reports. This recommendation remains unaddressed.

Another recommendation, which also remains unaddressed, holds that Permanent Secretaries ought to be free of partisan baggage or attachment to any political party, and that they would “selected upon merit by an Independent Civil Service Commission and not by the Prime Minister.”

Curb ‘positions of trust’

The Commission remarks that ‘persons of trust’ have proliferated in the recent years to around 700, and that these now include people doing work in administration, even gardeners and drivers – constituting, in the words of the Commission, “a danger to the quality of the civil service, which is the backbone of a democratic State under the rule of law.”

The Commission then recommended amending the Constitution to limit positions of trust to those employed in Ministers’ secretariats. Nothing has come of this recommendation.

Recent court testimony by Melvin Theuma, the alleged middleman in the assassination of journalist Caruana Galizia, showed how easy it was for him to be given a phantom job with the government through a chain of command involving ‘persons of trust’ in different Ministries.