The Dictator’s Handbook emphasises repeatedly how leaders stay in power by making sure their main supporters are sufficiently rewarded in one way or another. The most efficient thing for any leader to do would be to allocate resources in the form of private benefits to his or her cronies. This is because private goods to a few people cost a lot less then public goods to the masses, even when those few people are lavishly rewarded.

This system works well when a leader depends on a few key supporters (such as in an autocracy). Being dependant on a larger number of supporters (such as in a democracy) however, does not mean that there is no corruption – it just takes a different, less obvious, form.

According to authors Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith, the nature of private rewards in a democratic system comes in the form of distorted public policy that favours one group of supporters over another, rather than through the more shameless practices of outright bribery, black marketeering or extreme favouritism.

Of course, in Malta we have both; public tendering (a form of public policy) is often distorted by resorting to direct awards, and often this type of facade is done away with altogether and the shameless practices here mentioned are deployed next.

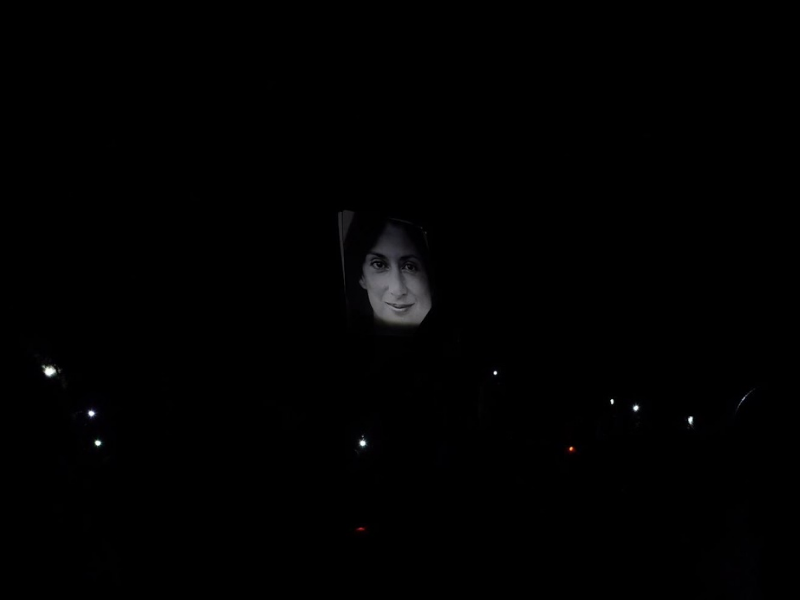

Maltese government officials are not only unapologetic in the face of numerous corruption allegations, but dig their heels in their stance and will go to great lengths to punish or discredit the journalists and whistleblowers who expose corrupt practices or even practices that can lead to corruption. If this is how those in power behave, are we to assume that corruption and corrupt practices are tolerated, or worse, encouraged?

For those out there who shrug their shoulders and say that it is only politicians who are corrupt and there is nothing that can be done, look at it this way: Corrupt practices do not only empower high ranking officials, because as soon as corrupt behaviour begins to trickle down to everyday services, it begins to empower the low ranking, poorly paid civil servant, the tired police officer on the beat, the bored traffic warden, and so on.

At the height of the Greek financial crisis in 2012, some villagers had to bribe the postman to deliver their mail. The postman now decides your letter’s fate – in his little world, the postman is now powerful. Is this what we want?

And for those who shrug their shoulders and say that corruption doesn’t really matter as long as business is booming: Sure, business is booming now but eventually, once corruption becomes entrenched, it will be too expensive or simply be too risky to do business in Malta, even from a reputational point of view. Serious international corporations will no longer want to take the risk of being fined, blacklisted or prosecuted no matter how many tax benefits we try to bait them with.

For those who say “to hell with it, I’ll pay the bribe to get what I want”, then the answer to this attitude is that not everyone is well connected and not everyone can afford to pay bribes, especially when it comes to public services that are public precisely to ensure that everyone benefits from them. If you introduce corruption into the equation, then many people start to lose out – usually society’s most vulnerable, such as the elderly or the poor.

Finally, and as a last reminder – because these things need constant reminding – corruption corrodes public trust, undermines the rule of law and ultimately de-legitimises the State, and it really doesn’t matter if the State is a member of the EU or not. Rules and regulations are bypassed by bribes, public budget control is undermined by illicit flows and political critics and the media are silenced.

If basic public services are not delivered to citizens due to corruption, the State eventually loses its credibility and eventually its legitimacy, with all the negative consequences to social stability that follow.

Read more in the series: The Dictator’s Handbook

Source: ‘The Dictator’s Handbook: Why bad behaviour is Almost Always Good Politics‘ by Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith.