“It is better to have loyal incompetents than competent rivals”

At long last, the aspiring politician has triumphed and now holds high office. That’s it – the new leader and his backers can now all live happily ever after, gorging at the public trough. But…hey, not so fast.

The skills needed to come to power are quite different to those needed to stay in power and they are not even the same set of skills that are needed to rule well.

So what must a newly appointed leader do to keep his proverbial head? We already know that he needs to amass a coalition of supporters because these supporters were needed to come to power in the first place.

Yet an astute politician knows that just because a group of people helped bring him or her to power, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will help him/her stay in power. A prudent new leader will therefore be quick to shuffle, trim and replace some of those initial backers with possibly cheaper and definitely more loyal individuals whose interests are more in line with the leader’s survival needs.

Authors Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith argue that this theory need not only apply to tyrants. It is also true of businesses. The point is that ruling well is not the objective; ruling, is.

Being good at your job is not enough to ensure political survival, even though it may seem obvious to us that, at the very least, those in power should be competent at whatever it is they have been tasked to do. This is not necessarily true.

In autocracies, being surrounding with competent individuals would seem like a rookie mistake and may even threaten the ruler’s hold on power.

After all, competent supporters may potentially turn out to be competent rivals. Successful leaders with autocratic tendencies prefer to surround themselves with close friends, family and advisors they know won’t rise to the top.

An example of what happens when a capable ally turns on you can be found within the Malta Labour Party’s own history. In 1949, then Prime Minister Sir Paul Boffa and his deputy leader Dom Mintoff disagreed on how the Labour government was to negotiate with the British about Malta obtaining a share of the Marshall Aid.

Unable to agree, Boffa decided to put the national interest first, concentrating on the negotiations while the more politically astute Mintoff concentrated on building his power base within the Party. Mintoff would then become leader of the Labour Party while Boffa was still Prime Minister. Six years later Boffa retired from the political arena.

Joseph Muscat did not make Boffa’s mistake and quickly identified those individuals within his own newly elected Cabinet who might pose a threat or, at the very least, ask inconvenient questions. So when former Health Minister Godfrey Farrugia was not going to sit quietly and do as he was told, he was summarily replaced.

Some removals were a little more subtle and cleverly masked as rewards, such as the appointment of Marie Louise Coliero-Preca as President.

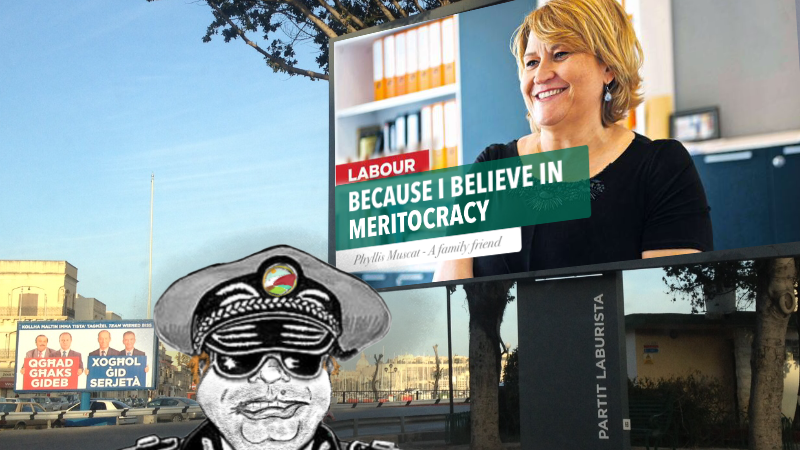

The finest example of loyal incompetents is Police Commissioner Lawrence Cutajar, whose skills are exactly what the authors of the book describe as: 1) loyalty, 2) loyalty, and 3) loyalty.

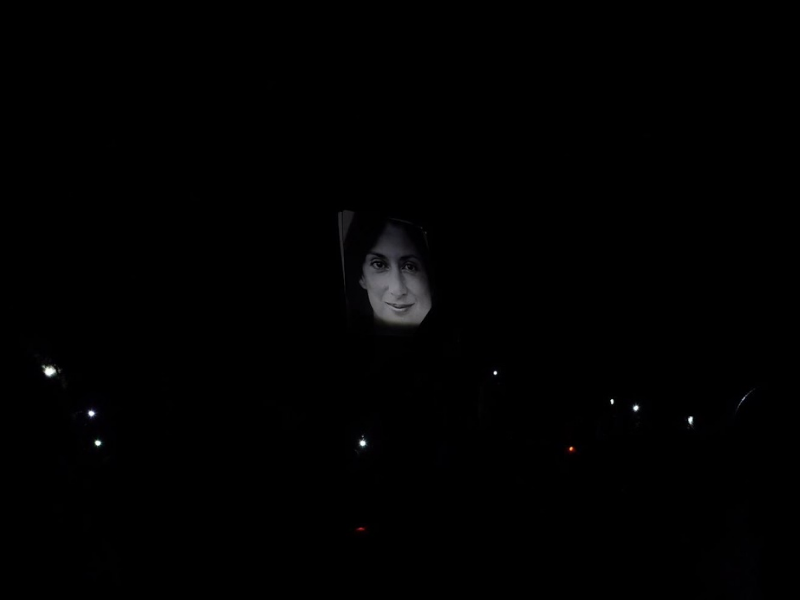

They are skills that are proving to be particularly useful in the wake of the high profile assassination of a journalist who was a fierce government critic.

And speaking of stellar press conferences, what about Phyllis Muscat, as head of the CHOGM task force who has now also been appointed Chairperson of the newly-established contemporary art museum? Qualifications? erm…

The list of loyal incompetents is long, but make no mistake there are instances where those in power need the advice of individuals who know what they are doing. For example, Brian Tonna and Karl Cini of Nexia BT – the accounting firm at the centre of the Panama Papers scandals in Malta – are extremely ‘competent’ accountants in terms of the particular skill set members of this government need.

Read more in the series: The Dictator’s Handbook

Source: The Dictator’s Handbook: Why bad behaviour is Almost Always Good Politics by Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith.