Despite the Attorney General’s apparent objections, Prime Minister Joseph Muscat has now promised to release a redacted version of the Egrant inquiry ‘report’. While we wait for the Office of the Prime Minister to selectively black out parts of the full report in which the Prime Minister is an interested party, and unleash a second wave of State-sponsored reputation washing, The Shift News takes a critical look at what has been released so far and what we can expect.

1. The Egrant inquiry ‘report’ does not rule on guilt or otherwise – it is a list of evidence collected

While everyone is referring to an Egrant inquiry ‘report’ and claiming absolution from all sins, this is not accurate.

Tourism Minister Konrad Mizzi posted a video on Facebook saying the inquiry absolved not only the Prime Minister, but also Mizzi himself, the Prime Minister’s chief of staff Keith Schembri and all others mentioned by assassinated journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia on money laundering and corruption allegations. This is not true.

This is not a conclusive judgement, ruling or result of some independent inquiry that can conclude on guilt or otherwise. In fact, the magistrate is not allowed to decide or state whether a person is guilty or otherwise (and did not).

The Egrant inquiry was what is known as an inquiry into the ‘in genere’ or material evidence of a crime. Its aim is for the magistrate (not a court) on duty at the time (in this case Magistrate Aaron Bugeja) to proceed to preserve any evidence of a possible crime whether alone or (more often than not) with experts’ help.

The end result of an inquiry into the ‘in genere’ is typically a lengthy document called the acts of the proceedings or procès-verbal, which is a record of the evidence collected.

This could in turn be used for further investigation by the AG and the police, if there is enough evidence (or appetite, which seems to be perpetually lacking), to commence proceedings in Court – the only place where guilt or absolution may be awarded – in which case the procès-verbal is filed as evidence.

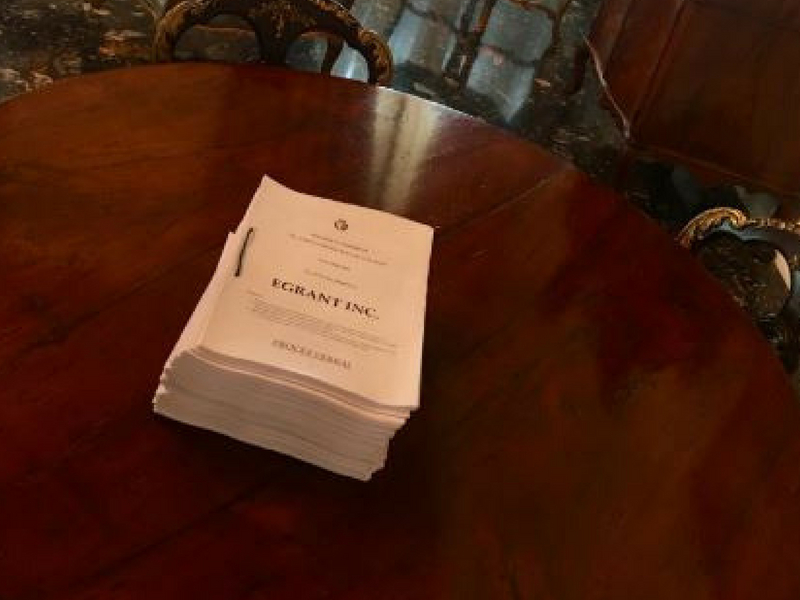

This is what you can see sitting on the table at the Office of the Prime Minister, and why it is so lengthy.

The full Egrant inquiry shown on Twitter by Prime Minister’s Head of Communications Kurt Farrugia.

It is also worth bearing in mind that the investigation of offences is, and remains, the responsibility of the police. It is this police investigation (except in instances where the police evidently refuse to act) which, in the vast majority of cases, will ultimately determine whether a person will or will not be charged in court.

2. What would the ‘report’ normally contain and what was released so far?

The procès-verbal must include:

- A short summary of the report, information or complaint,

- A list of the witnesses heard and evidence collected (including actual depositions, expert reports, photos and other evidence),

- A final paragraph containing the findings of the inquiring magistrate,

- It must also be signed by the magistrate.

From the above, it seems that the 49 pages released would be the short summary as well as a part of the final findings. The signature page seems to have been omitted so it seems there is at least another page of the conclusions or findings that was held back.

As for findings, the Maltese Courts have made it quite clear in the past that it is not the function of the inquiring magistrate to decide who is responsible for the offence in question.

Maltese judgements have held in the past that the magistrate conducting the inquiry should only state whether, in the magistrate’s view, an offence has been committed and whether criminal proceedings should be instituted against a suspect.

3. Are the findings of such an inquiry unquestionable?

Since a procès-verbal is a collection of evidence – it has the weight of evidence in court – it is subject to all other rules of evidence and accordingly is open to challenge (including the experts or its scope) or may even be disregarded altogether.

Even the AG has the power to disagree with the procès-verbal and its conclusions. Accordingly, the AG has the power to send the procès-verbal back to the magistrate to continue the inquiry and hear further witnesses.

Chris Fearne, now one of Joseph Muscat’s deputy leaders and presently tweeting about this inquiry, in 2003 saw an inquiring magistrate conclude that there was enough evidence to press charges against him. The AG at the time did not agree with its conclusions and opted to apply what is known as nolle prosequi, effectively overriding the magistrate.

4. The scope of the inquiry was actually very limited

There is a simple reason why everyone felt that each time a new piece of evidence of corruption emanating from Panama Papers and the leaked FIAU reports was presented to the magistrate, a new inquiry seemed to open. The terms of reference of the Egrant inquiry were rather limited.

The formal complaint that Muscat made to the Police Commissioner through his lawyers Pawlu Lia and Edward Gatt essentially limited the magistrate to two really narrow questions:

- Is there any evidence that the shares in Egrant, a Panamanian company established in 2013 using Mossack Fonseca and Nexia BT services, owned by Michelle Muscat or are otherwise attributable to her or her husband the Prime Minister?

- Is there any evidence that the Prime Minister and wife, Keith Schembri, Konrad Mizzi or John Dalli engaged in any illicit dealings through bank accounts at Pilatus Bank with Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) from Azerbaijan?

How can we be sure that the 1,500-page report will be redacted fairly? Muscat has a massive conflict of interest here to ensure that the full report does not include any details or evidence that might cast him or others around him in a bad light

In this context, the questions asked did not cover, for example:

- Acts of corruption, money laundering or suspicious transactions by those five people with persons other than Azeri PEPs;

- Illicit dealings by persons other than those five individuals even if with Azeri PEPs and using Pilatus Bank accounts;

- Whether all was fine and dandy at Pilatus Bank, Mossack Fonseca or Nexia BT or whether the persons named should have used their services at all; or

- Illicit dealings even by those five individuals (including their Panama companies) or any of them with Azeri PEPs using other bank accounts than those at Pilatus Bank (such as banks in Dubai).

This limitation in scope is important since the summary does include clues about matters that, while not included in the strict terms of reference, provide clues about what we can expect in the other inquiries.

Given that the 1,500-page ‘report’ will include the full testimony of several witnesses we can expect more of these clues and details to emerge about other matters that did not fall within the original scope.

That is unless they are conveniently redacted…

Michelle Muscat withLeyla Aliyeva of Azerbaijan, in Malta in 2014.

5. The OPM and the AG are controlling what gets released

At law, a procès-verbal is only made available to the AG. This is because the AG would normally use the evidence and recommendations in it to either investigate further, press charges in Court or otherwise decide what to do with it.

An interested party such as Joseph Muscat – since he filed the original police report – may request the AG for a copy and, if the AG agrees, a copy may typically be provided against payment of a fee. We have neither seen a receipt nor have any details of who paid the fee.

Other people may ask for a copy, but the AG has discretion to refuse. In fact, he has so far refused a request by Opposition Leader Adrian Delia or, generally, to publish the procès-verbal. This refusal has been explained as being the fact that the procès-verbal includes details of witnesses and evidence as well as names of potential suspects.

The problem here is two-fold.

We can expect to see a document that is more heavily redacted than the Enemalta or Vitals documents, but which includes more information than necessary where convenient.

So far, a 49-page extract has been published and paraded by the government as though it is an incontrovertible clean bill of health. It has also been used to accuse others of a frame up, and to discredit any journalist that ever reported any wrong doing, including Daphne Caruana Galizia.

The full procès-verbal will, however, offer a more nuanced picture, with full transcripts of witnesses giving evidence, details of transactions, copies of documents and similar information, rather than the magistrate’s own assessment and highlights of perceived inconsistencies.

The second problem is perhaps more serious. Muscat received a copy as an interested party, but he would not be permitted to disclose that to suspects or other persons which may prejudice further investigation, imperil witnesses or damage other inquiries.

He has promised nevertheless to publish a redacted version of the full report, which is being held at the OPM, a place where people were named in that report and investigated, and which may include evidence relating to matters outside the scope of the inquiry. This means that potentially people such as Keith Schembri, Konrad Mizzi and others have access.

Also, unless Muscat handles the redaction personally he will need to disclose the full report to others. Further, and this part is key, can we be sure that the 1,500 page report will be redacted fairly?

Muscat has a massive conflict of interest here to ensure that the full report does not include any details or evidence that might cast him or others around him in a bad light. It is that simple.

The Maltese government has aggressively marketed the summary of the inquiry as an unconditional cleansing of the slate. Accordingly, we can expect to see a document that is more heavily redacted than the Enemalta or Vitals documents but which includes more information than necessary where convenient.

The selective and shrewd dripping of information on this inquiry is feeding propaganda that twists the narrative before people are able to digest and question, and even then the key pieces of the puzzle are hidden.

6. The Magistrate does not (in the summary) refer to any form of frame up

The magistrate concluded that the declarations of trust presented by Pierre Portelli to the magistrate and naming Michelle Muscat as the “beneficial owner” of the shares in Egrant were to be deemed a forgery. Why is this?

Under Maltese law a signature is only evidenced if: (a) the signature is witnessed by two persons (or a lawyer) or (b) the person that signed confirms to the magistrate in this case that he or she actually signed (called attestation).

The signatures of Mossack Fonseca sham director Jaqueline Alexander were not witnessed. Also when giving her testimony, Jaqueline Alexander seems to have disavowed the signatures and declarations of trust saying she did not write or drawn up those declarations of trust and that the signatures are not hers.

While this is not entirely surprising given what we know about Mossack Fonseca’s practices as exposed in the Panama Papers, what this meant is that the declarations of trust would, at law, be deemed forgeries since the author is contesting authorship.

We also know that Mossack Fonseca did not always abide by the law including instances of telling clients to forge signatures, back-date documents or sign them in blank.

What is certain is that the magistrate did not have the power or any reason to decide on malicious intent or call anything a “frame up”.