Emotionally charged language, personal attacks, false comparisons, and deliberate incoherence are some misinformation techniques readers encounter in Malta’s daily political discourse, but the issue is expected to reach a new level of complexity beyond the bluster of our politicians, according to a new report.

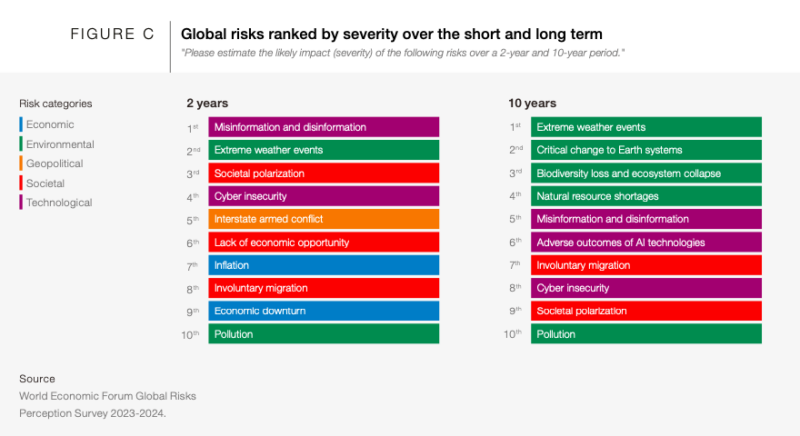

According to the Global Risks Report 2024 by the World Economic Forum (WEF), misinformation and the climate crisis are expected to be the greatest global risks in the immediate future.

With nearly four billion people heading to the polls over the next two years – including in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, the United Kingdom, and the United States – the report highlights the heightened potential for foreign and domestic actors to use misinformation and disinformation to widen social and political divides further and undermine the legitimacy of newly elected governments.

The report is based on an annual ‘Global Risks Perception Survey,’ which brings together insights on the evolving global risks landscape from 1,490 experts from academia, business, government, the international community, and civil society.

It’s never been easier or quicker to create false content

Disinformation secured the top spot in the list of risks because creating false or misleading content no longer requires a specialised skill set. With the availability of user-friendly interfaces and large-scale AI models, there has been a sharp increase in false information and so-called ‘synthetic’ content.

Governments are introducing new and updated regulations to address online disinformation and illegal content created by hosts and creators. Examples of such regulations include the EU’s AI Act and the agreement among 28 countries to collaborate on AI development. However, according to the report, it is unlikely that the speed and efficacy of regulation will keep up with technological advancements.

Polarisation and mistrust in authority

Disinformation techniques, however, are much older and go beyond the evolution of AI interfaces. The report describes how the survey respondents see misinformation, disinformation, and societal polarisation as the most strongly connected risks with the most significant potential to amplify each other.

The report also notes how information disseminated by public figures, media organisations and states can shift public opinion and undermine trust in authority.

Many of the consequences of disinformation highlighted in the report can easily be found in the rhetoric used by our homegrown politicians, the party-owned media that support them and the career propagandists whose job is to secretly nurture polarisation for political expediency.

There is no shortage of examples of how Malta’s government officials deliberately make misleading claims to cast doubt on the competencies and legitimacy of public institutions when faced with incontrovertible evidence and scrutiny.

One of the most recent examples is Prime Minister Robert Abela’s repeated attacks on the judiciary in anticipation of potentially disruptive findings of a magisterial inquiry into alleged corruption by disgraced former prime minister Joseph Muscat.

Another example is how, when faced with the pressure for the government to hold a public inquiry into the death of Jean-Paul Sofia, several government figures, including the prime minister and Justice Minister Jonathan Attard, repeated the false claim that a public inquiry would serve the same purpose as a magisterial inquiry.

Change works both ways

Nevertheless, even as disinformation techniques evolve, so have the tools to counter them.

Researchers have identified novel ways to make people more resistant to being misled without the risk of censorship or interfering with anyone’s freedom of speech. One technique is “inoculation,” which involves boosting people’s information discernment skills.

Key to inoculation, or “pre-bunking”, as it has come to be known, is the realisation that misleading or false information has markers that can help differentiate it from high-quality information. These markers include emotionally charged language, personal attacks, false dichotomies, and deliberate incoherence are just some of those markers.

For the Maltese context, the Labour Party’s “you’re either with us, or you are traitors” rhetoric is a good example of a false dichotomy. Blaming activists and the media for the Nationalist Party’s electoral defeat in 2022 or blaming foreigners for a perceived rise in crime are good examples of scapegoating.

Studies rolled out to millions of people on social media have shown that inoculation using brief informational videos makes people more skilled at identifying manipulation techniques common in misinformation. Equally hopeful is a study by Google published in 2022, which found that younger people are more likely to think they may have unintentionally shared false or misleading information but are also more skilled at using advanced fact-checking techniques.

The full Global Risk Report can be found here.