What do misleading headlines by party-owned media, statements by propagandists, and the distorted rhetoric of our politicians have in common — apart from their ubiquity and their negative impact on public debate?

A new study suggests that another element which makes misinformation so pervasive is that it requires less mental effort to process than factual news because the language used in deceptive content is simpler and relies on eliciting an emotional response.

“Not all misinformation is created equal”

Finding a way to mitigate the spread of increasingly sophisticated disinformation and misinformation remains one of the most pressing questions in global social, political, and media circles.

According to research, deceptive content is driven by volume, breadth, and speed. Volume refers to the sheer quantity of misleading and false content, breadth denotes the different types of misinformation (rumours, clickbait, junk science, conspiracy theories, etc.), and speed refers to the fact that deceptive content spreads six times faster than accurate information.

These three elements make it difficult for current fact-checking and reporting tools to counter the spread of suspicious content.

Research published last week in the journal Nature by Carlos Carrasco-Farré analysed over 92,000 news articles to better understand the “fingerprints of misinformation”, and how factual news differs from misinformation in terms of eliciting emotions (sentiment analyses) and the mental effort needed to process the content (grammar, readability, and varied vocabulary).

The results of his analyses show that misinformation, on average, “is easier to process in terms of cognitive effort (3% easier to read and 15% less lexically diverse) and more emotional (10 times more reliant on negative sentiment and 37% more appealing to morality).”

Grubby fingerprints everywhere

Misinformation is written with a style that seeks to maximize reading, sharing and, ultimately, virality. And since people generally attempt to minimize mental effort when processing information, any content that requires less effort to be processed becomes more engaging and popular.

Articles published by Malta’s party-owned media are good examples of how a certain writing style is used to maximise reading with little effort while using limited vocabulary. Terms such as “traitors”, “working against Malta”, and “hatred” appear in articles and headlines by party-owned media, government mouthpieces, and in partisan speeches by politicians, and are a warning sign that emotions are being deliberately manipulated.

Another fingerprint of misinformation is reliance on eliciting an emotional response. In general, content that evokes high-arousal emotions spreads more quickly, particularly if that emotion is negative.

This premise was further confirmed by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen who revealed that the social media giant amplifies divisive content to earn more money. She explained that it is easier to elicit user responses by presenting them with controversial or hateful content which drives up engagement and makes them spend longer on the platform, increasing Facebook’s profits.

Our homegrown examples

Local examples of misinformation in action are easy to find. Two police reports were filed in April 2020 by the NGO Repubblika, which asked the authorities to investigate whether the army or the prime minister were in any way responsible for the death of migrants at sea because they failed to rescue them.

Prime Minister Robert Abela responded by calling a press conference where he said that those who filed the complaint wanted to see him and army officials “serve life in prison”.

Memes immediately surfaced on social media labelling the four signatories of Repubblika’s reports as ‘traitors’ working against Malta during a global pandemic. By suggesting that possible harm might come to Abela (and therefore to the nation itself), the prime minister was able to arouse feelings of fear and emotional rapport in his supporters. The prime minister’s supporters took it further by sharing his message and inflicting harm on others.

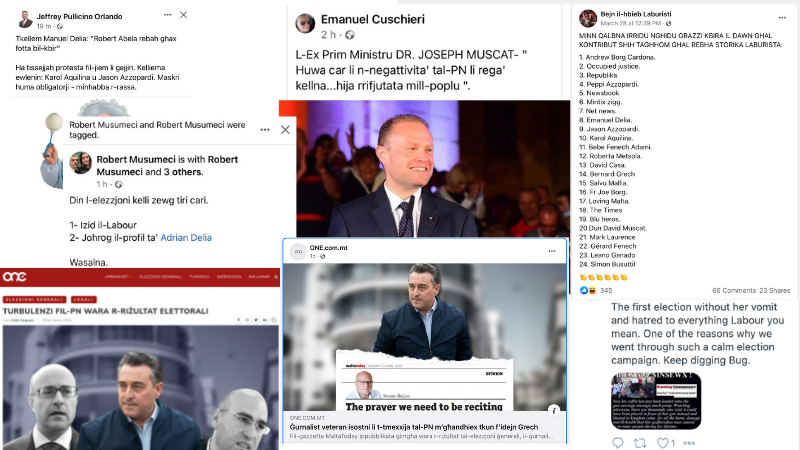

More recently, negatively framed narratives (known as negativity bias) were published on the governing party’s social media and news channels following their election victory, and post-electoral propaganda chatter included efforts to blame civil society groups, independent journalists, and private individuals for the Nationalist Party’s defeat thanks in part to ‘too much reporting’ about the PN’s internal strife.

Studies of how people process information based on how it is presented to them have found that negative attacks during a political campaign influence everyone, even a Party’s own supporters. Once a negative idea has been planted, it’s very hard to shake.

Samples of the social media commentary by government propagandists following the Labour Party’s electoral victory.

Negative content also spreads more rapidly and more frequently than positive or neutral content, and content that relies on eliciting emotion is associated with the sharing of misinformation.

There may be no quick fix to this problem, but Carlos Carrasco-Farré’s latest analysis aims to help “technology companies, media outlets, and fact-checking organizations to prioritize the content to be checked”, thus becoming another important tool for understanding and countering of misinformation.

The full study on the fingerprints of misinformation can be found here.