An investigation on a site in Iklin flagged by our readers for sprawling development in what was once an agricultural zone, has revealed a chequered history of illegal development and use, later sanctioned by the planning authority, or its tribunal, as permits were issued despite years of enforcement notices ignored.

An analysis of the site’s permits and enforcement notices indicates that the site, located in Triq il-Ħwawar, was originally an agricultural zone, similar to the area that is now a ‘concrete belt’ in Għaxaq.

Through repeated instances of abuse of planning laws and the practice of building first and sanctioning later, the Bitmac Ltd site has mushroomed over the years and has become a production hub for the raw material that is later used in the roadworks projects in which Bitmac’s shareholder companies are involved.

Appeals, sanctioning permits and rationalisations

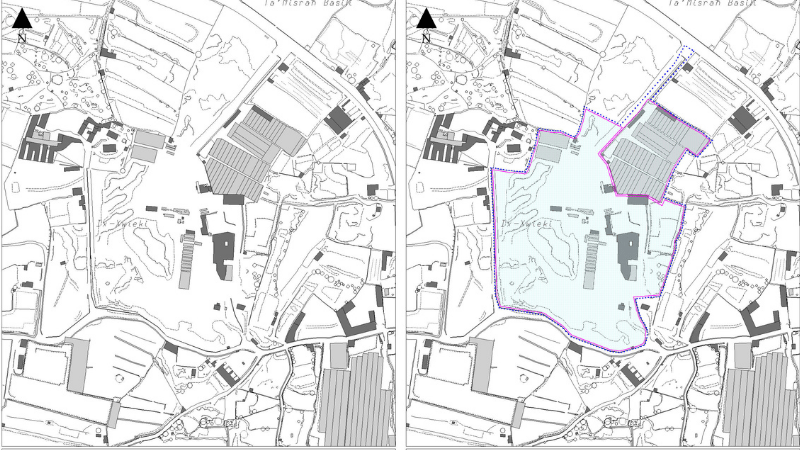

An aerial view of the area occupied by Bitmac Ltd in Iklin.

The earliest PA application available online dates back to 1994 (PA/05120/94). Bitmac had filed for permission to construct a warehouse. This application from 27 years ago was to be the beginning of a piecemeal process that led to more and more land being taken up.

The application had been recommended for refusal, which was confirmed by the planning board in 1996. Another appeal was filed to reconsider the decision, with that being thrown out yet again in 1998.

Undeterred, Bitmac Ltd proceeded to follow through with plans, with an enforcement notice from 1997 detailing that the applicant “intensified commercial operations (illegal extension to factory boundary) on land that extends beyond the original site as well as change of use of that same land wherein materials used for construction are being stored, all without a permit” (EC/01084/97).

A key aspect of the gradual change from agricultural land to an industrial hub is the frequently used tactic of delaying the effects of enforcement notices via long, drawn-out appeals. While PA enforcement notices usually subject the entity committing illegalities to daily fines of up to €50 per day, an appeal essentially freezes the enforcement notice in place until it is decided.

The applicant filing on behalf of the company, Hector Camilleri, did in fact take the appeal to the environment and planning review tribunal (EPRT) in 2000. The EPRT’s ruling sanctioned the development, and also rewarded the developers since the commission for development control (the deciding body at the time the enforcement notice was issued) was fined Lm150 for ‘damage suffered’ by the applicant and ordered to issue the payment within 30 days.

In 1998, merely a year after being slapped with an enforcement notice for conducting works without permission, the applicant applied for “extensive landscaping” and “an extension to existing administrative building”.

The application, PA/03203/98, outlined how Bitmac Ltd sought to change the use of significant chunks of land in order to “store aggregates for asphalt production” as well as the retroactive sanctioning of “heavy plant vehicles garage, store and maintenance garage; and boiler room, tools store, shower, W/C and anteroom”.

In other words, while Bitmac Ltd was waiting for a verdict on enforcement action that would come two years later, the company had already set its sights on further expansion and had applied for permission to do so.

The development, on ODZ land, was approved. Any other PA applications Bitmac Ltd filed for the building of more heavy plants, garages and workshops after that were approved, even when refusal was recommended.

The local plan based on the rationalisation exercise of 2006.

As happened with the other sites in Għaxaq investigated by The Shift, the site owned by Bitmac Ltd was designated as an area of containment in the rationalisation exercise of 2006, meaning that development was to be contained within its footprint and not allowed to expand further.

The site’s most recent enforcement notice is EC/00050/19 issued two years ago when Bitmac Ltd was storing electronic waste on site. The company simply appealed the enforcement notice again. The appeal remains pending, with four out of nine sittings cancelled.

The enforcement notice was issued after the press had flagged Wasteserv’s unexplained decision to award a €1 million direct order to Bitmac Ltd to ‘temporarily’ store waste in the location after civic amenity sites had started overflowing.

Although Wasteserv has not yet replied to questions about why the direct order was issued in spite of the fact that the facility did not carry permits to store such waste, the agency did say that “there are no current contractual ties” between Wasteserv and Bitmac Ltd.

The planning authority, Bitmac Ltd, and the EPRT have all been contacted with a request for comment on questions related to this article. All three have not replied to questions.

Family-owned businesses

A look into the ownership structure behind Bitmac Ltd reveals a complex network of locally-registered companies. The shareholders of Bitmac Ltd are Naipaul Developments, Schembri Barbros and V&C Investments.

An analysis of the three shareholders behind Bitmac Ltd indicates a close, tight-knit group of families exerting a large degree of influence in the construction sector, especially with the state’s infrastructure projects.

The controlling directorship of all the shareholding companies is largely in the hands of the Magro, Schembri and Borg families, whose business interests extend into several other commercial sectors.

The Magro and Borg families, for example, are both involved in the consortium Link 2018 JV, the entity awarded the controversial Central Link project, now expanded as an underpass that was not in the original tender was added to the project.

Link 2018 JV includes one of V&C’s construction arms, Schembri Barbros and Schembri Holdings.

The Schembris, acting via Schembri Barbros on behalf of the Barbros Group, also jointly own a company known as ABB Ltd, whose shareholders consist of one member of each family – Vincent Borg, Paul Magro and Anthony Schembri.

One of the concrete production hubs recently highlighted by The Shift is owned by Schembri Barbros.

Not only that but they don’t even seem to care about containing the dust. Tal-Ħwawar Road is full of dust that gets blown by the wind and it stinks badly. That road’s supposed to be an alternative road for cycling, now that Tal-Balal has become so bloody dangerous. But when it’s a little bit windy you get caked in dust when you take that road.