On 1 September the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life published a report that addresses how persons of trust should not comment on matters of political controversy and should treat others with respect.

The complaint was filed by Matthew Caruana Galizia against Joseph Borg concerning a Facebook post in which he defended Minister Michael Farrugia and directed an insult at Professor Arnold Cassola.

Borg’s post tried to justify Farrugia’s behaviour after it had been revealed that the Minister had ordered a change to a high-rise policy on the same day he met with chief suspect in the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia, Yorgen Fenech. Borg went on the conclude the post by insulting Cassola, saying “just get a life…”.

When Borg wrote the Facebook post he was a person of trust at the Home Affairs Ministry and, ironically, Head of the Hate Crime and Speech Unit.

His contract expired on 7 June and, as he wrote to the commissioner’s office, he was now “just a normal citizen that wishes to be left alone and not harassed by you, your department nor the commissioner”.

Well then, leave the man alone please.

The Hate Crime and Speech Unit was set up in October 2019 with the aim to assist those who were the target of hate crime or hate speech as well as to educate and raise awareness with the public on what is fast becoming a pervasive element in much of the country’s public dialogue.

Yet, as of 7 June, there appears to be no one directing the unit.

The insult directed at Cassola is trivial when compared to current standards, but it points to a broader issue, namely that those in power have done little to set an example of appropriate behaviour. Quite the opposite is true.

What’s more, politicians, propagandists and troublemakers alike thrive when sowing the seeds of confusion on what defines hate speech and freedom of expression.

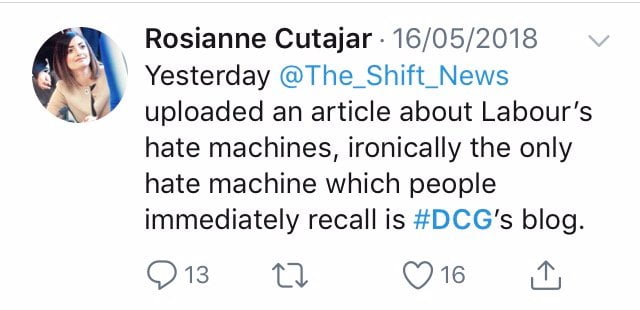

Remember Parliamentary Secretary for Equality and Reforms Rosianne Cutajar defending insults against Caruana Galizia in the Labour Party’s online groups as ‘freedom of expression’? The journalist was killed.

Or government whip Glenn Bedingfield in the public inquiry defending his attacks against the same journalist from his seat at the Office of the Prime Minister also as ‘freedom of expression’?

This blurring of lines does not work in the public interest, especially when citizens and journalists are being attacked by members of the government.

What is freedom of expression, exactly?

Broadly speaking, freedom of expression is the right to say whatever you like. What you say doesn’t need to be reasonable or objective, doesn’t require factual accuracy and it doesn’t matter if your opinion is widely unpopular.

You are free to convey your ideas and opinions and you are free to hear what others have to say without interference from the State.

It is considered a fundamental human right because it underpins all civil liberties and is an enabler of all our other rights. It is protected by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In Malta, it is protected under Article 41 of our Constitution.

Fundamental doesn’t mean absolute

The scope of the right to freedom of expression is extensive and therefore includes the communication of opinions and ideas that others may find obscene, deeply offensive and discriminatory. Which is why the right to freedom of expression is not absolute.

The State may, under certain exceptional circumstances, restrict your right to free expression under international human rights law.

A good rule of thumb is to remember that if what is said in the purported exercise of your freedom of expression violates the rights of another person, group of people or the core values of society as a whole, then the State can lawfully restrict that expression.

This is not as self-defeating as it sounds. While the scope of freedom of expression is broad, that of its restriction is narrow.

Any restrictions to an individual’s freedom of expression have to pass what is known as a three-point test:

- They have to be established by a law which is clear, to avoid arbitrary application,

- They must pursue a legitimate aim, namely the protection of other fundamental rights or core values,

- Most importantly, there must be an element of proportionality between the means and extent of the restriction and the achievable and legitimate aim.

What is hate speech?

First, just because we may find something offensive or shocking, doesn’t automatically make it hate speech. Secondly, there is no universally accepted definition of ‘hate speech’ under international human rights law.

The United Nations, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe and Malta’s Hate Crime and Speech Unit website all define hate speech using slightly different criteria.

All of which are, in turn, a little different from Article 82A of the Criminal Code with reference to the crime of incitement to racial hatred. What is highlighted in this case are expressions and conduct intended to stir up racial hatred, but the text is so convoluted and overreaching that it raises the question of what exactly the authors had in mind when drafting this particular law in Malta. Clarity was not high on the list of priorities.

Yet all the texts have two elements in common:

- The first is that the person ‘doing’ the hating has identified something in their target upon which to ground the ‘us’/ ‘them’ dichotomy, such as the colour of the skin, religious beliefs or gender.

- The second is the word ‘incitement’, which means that what you’re saying or the way you’re saying it, is provoking or urging others to act, often unlawfully.

One of the memes reproduced in Labour Party online groups is the scene in which Pontius Pilate asks the crowd “What shall I do, then, with the one you call the king of the Jews?”, placing Daphne Caruana Galizia as the subject of the question. She was later assassinated.

The problem remains that even these two points fall on a spectrum of expressions and behaviour that ranges from speech or conduct that raises concerns about intolerance but may still be legal, all the way to incitement to genocide and other gross violations of international law.

Everything that falls in between remains a matter of fierce debate.

The weaponisation of terminology

Umbrella terms such as “free speech” and “hate speech” are a godsend to politicians. Those in power get to pick what they deem as hate speech or free speech depending on their needs.

For some time now, hatemongers have found it strategically useful to present themselves as defenders of free speech. By shifting the focus on the defence of free speech instead of the contents of the message, the speaker can make hateful and harmful content more palatable to his audience.

With a little boost from media outlets desperate for clicks, the messages of hatemongers, masked as free speech martyrs, can easily be picked up, repeated, amplified and rendered credible.

Some notable examples

What criteria Franco Debono used when he reported what singer Mario Vella had to say about him as hate speech, is anyone’s guess.

Vella’s comment included calling Debono a narcissist without scruples and went on to use a sexually explicit insult to make a point about what he thought of those individuals encouraging Debono to run for the post of Opposition Leader.

The content may seem vulgar and offensive to those it was aimed at insulting. However, there appears to be nothing in the content or context of this insult that is urging others to behave unlawfully or violently towards Debono.

Contrast this with the example of the individual who posted a video online in which he described African migrants using the worst possible terms and went on to add that if one of these migrants so much as looked at his children, he would go on a genocidal rampage that would land him in prison for a long time. As he put it, “inkaxkar lis-suwed kollha, diżastru nagħmel Malta” (‘I’d drag all blacks, I’ll create a disaster in Malta’).

The difference is pretty clear. A group of individuals is being targeted based on who they are, using abusive language and threatening to respond with violence.

The messenger then asked viewers to share this video and many did, helped by media outlets that turned this into a news item, amplifying the message. The video had been seen over 200,000 times and shared 4,000 times before it was taken down.

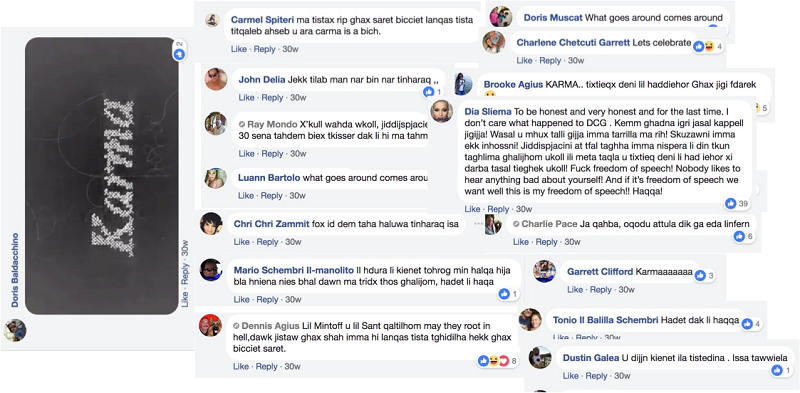

Two years ago, an investigation by The Shift into six of the biggest pro-Muscat Facebook groups – numbering 60,000 members – found coordinated harassment of anti-corruption activists and Caruana Galizia’s family, including calls for sexual violence.

Celebration of Daphne Caruana Galizia’s death in Labour hate groups exposed by The Shift.

Many of the comments included depicting targets in murder fantasies and posts celebrating Caruana Galizia’s assassination. This kind of coordinated harassment is not an expression of free speech but a deterrent, designed to silence, which is how online government-sanctioned trolling works.

Not only did those in government not distance themselves from these groups, Parliamentary Secretary for Equality and Reforms Cutajar went on to defend them in a lengthy speech.

If Cutajar was unable to tolerate misogynistic attacks directed at her, something she had a right to do, she can’t make a roundabout turn and defend messages that were far worse simply because they were directed at someone who was extremely critical of her. That’s cherry picking.

So what kind of ideas and information did the two soldiers who are believed to be behind the drive-by shooting of Lassana Cisse consume? What compelled them to act?

Back in 2013, what exchange of ideas propelled the Mayor of Zurrieq Ignatius Farrugia to call the attention of another two people so as to insult and accost Caruana Galizia, causing a commotion and forcing her to take shelter inside a Franciscan convent, while individuals shouted to bring her out like some sort of medieval frenzied mob?

We don’t quite know but we can guess.