The creation and spread of false or deliberately misleading information is not new. As a teenager in the 1990s, fake news didn’t exist. Or rather, it did, but we tended to call it an urban legend.

These were improbable, ridiculous and often grotesque stories that were told and retold to the point that they took a life of their own, entered our collective knowledge and then simply sat there, unchecked, until the next absurdity “that happened to a friend” came along.

One major difference now, apart from the terminology, is the mind-boggling speed with which false narratives are amplified to reach anyone with an internet connection or smartphone, anywhere in the world. During a global pandemic, this is a major concern.

In 2016, Facebook and Twitter were largely blamed for housing foreign disinformation campaigns that interfered with the US presidential elections, but a 2018 report commissioned by the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence suggested that Instagram was “perhaps the most effective platform” for disinformation than was commonly understood.

How did Instagram escape scrutiny for so long?

Pretty pictures

Instagram – bought by Facebook in 2012 – started out as a photo-sharing platform where users post carefully selected pictures to their “grid” (all the user’s images grouped together under their profile).

For those who had grown weary of Facebook’s busy interface and cumbersome privacy controls, Instagram was a great alternative for sharing their photos without all the extra clutter.

Over the years, it went on to introduce features that made sharing and reposting easier, allowed text to be used alongside visuals and allowed lengthy videos to be uploaded. Every new feature was designed to attract user interaction, and it worked.

In June 2018, Instagram had reached one billion monthly active users, up from 800 million in September 2017.

Last year, Instagram’s top 10 accounts generated six billion interactions (likes and comments) compared to Facebook’s 922 million (reactions, comments and shares) and Twitter’s 398 million (retweets plus likes).

This combination of text and sharing, coupled with a huge user base, has made Instagram much more like Facebook—and, therefore, irresistible to businesses, advertisers, politicians and propagandists.

“Instagram has been a problem all along, but for whatever reason, we don’t pay as much attention to it,” according to Paul Barret, author of the report ‘Disinformation and the 2020 Election’.

Perhaps because it is still regarded as a place for harmless snaps of beautiful sunsets, coffee cups and celebrities flogging their brands, users lower their guard.

Visual disinformation

How does one spread disinformation on Instagram? Easy. Just create a meme, tamper with videos and photos and share. Instagram will do the rest.

Just like Facebook, Instagram rewards sensational clickbait with algorithmic promotion. As you click false content, Instagram will show you more false content to click on— not only legitimising it but also encouraging people to produce more of it.

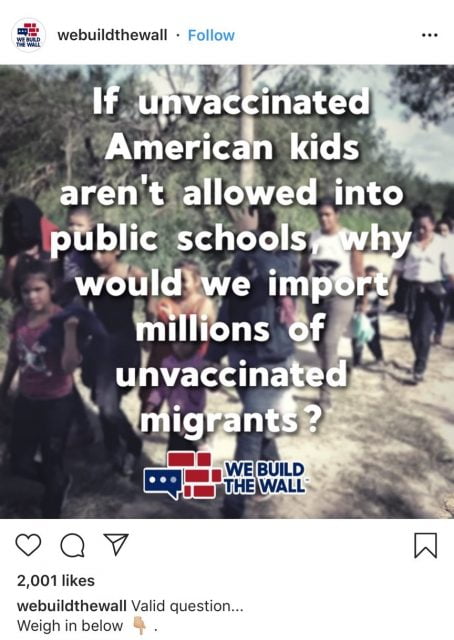

The anti-vaccine movement in the US is an example. Anti-vaxxers are in a minority but, as the Huffington Post quickly found out, their message can very easily be disproportionately amplified.

When searching the word ‘vaccine’ on Instagram, almost all of the top results were anti-vax pages. The most popular account was a profile with more than 74,000 followers with posts pushing blatant lies about vaccines and the Wuhan coronavirus.

As soon as The Shift’s journalist followed that account, Instagram recommended dozens more promoting dangerous misinformation.

Tech’s lukewarm response

The problem with false images is that they are a lot harder to verify than a website link or a news article. In the face of mounting criticism, in August 2019, Facebook launched a test programme that uses image recognition to find questionable content on Instagram. Instagram users can now also flag dubious content they come across.

An Instagram post claiming to have found the vaccine for coronavirus.

This is still a Facebook company, so the effort is merely cosmetic. Users with the latest version of the Instagram app will see “false information” at the bottom of a list of reportable items. Yet, if Instagram decides that a post has been correctly flagged as false, it won’t delete it – Instagram will just limit the post’s reach by hiding it from the public ‘explore’ feed.

Another reason disinformation campaigns on Instagram have remained largely underreported (when compared to Facebook) is that, in 2018, Instagram abruptly shut down its public API (Application Programming Interface), which is a service that processes requests for data from remote applications.

In short, Instagram has made it near impossible for researchers and journalists to gather any meaningful data about the spread of disinformation on the platform. Without this information, there is less to report on and, therefore, less pressure on Instagram to make any significant changes.

Younger users

Disinformation on Instagram is drawing the attention of journalists and researchers because young users – teenagers – are turning to visual platforms like Instagram and YouTube to get the news that informs their world view.

Reports warn of the danger of dismissing teenagers’ news consumption patterns due to the impact it will have on politics, industry and society.

If a young audience consumes news that is created by personalities instead of newsrooms, and if this information is a weird melting pot of celebrities, activism, memes and conspiracy theories, it is not that hard to imagine what the proliferation of false content could do to future public discourse. It is unrealistic to expect young users to constantly fact-check what they’re viewing.

There is much that the tech companies behind these platforms can do to counter this trend but if they keep skirting the issues, then public awareness of their role in the dissemination of disinformation is crucial. During a pandemic, there are severe repercussions for all.