There’s a scene in a film called Matilda – based on a children’s book by Roald Dahl – where the film’s character points out to her cheating salesman dad that his selling run down cars to unsuspecting customers was criminal. His response:

“Listen you little wise-acre, I’m smart you’re dumb, I’m big and you’re little, I’m right and you’re wrong – and there’s nothing you can do about it”.

It may have been my first introduction to fascism.

I didn’t like the authoritarian – and often patronising – tone that many (though by no means all) of the teachers adopted with us at school.

By way of example, I remember our ‘Head Boy’ – Malta’s answer to the boarding school ‘Prefect’ – being caught cheating in one of his exams. He was, like most of us, under a lot of pressure to perform.

When he was caught I expected him (naturally) to lose his position. How could he retain authority over us when he had betrayed his responsibilities?

When he wasn’t dethroned, I organised a petition. It wasn’t personal; but the hypocrisy of it stank. How could teachers ask us to behave while rewarding bad behaviour?

The headmistress at the time caught wind of this and called the entire grade into the assembly hall. She told us not to bother with our silly petitions because she believed that the boy was the best person for the role. At one point she went so far as to say, “I believe he is better than all of you, so don’t bother with your petitions because I’m not interested”.

As I completed school, attended Sixth Form, and then enrolled at the University of Malta, I began to note that the same heavy-handed, top-down, didactic approach to education followed me through all these institutions and the effect it had on everyday discussion with my peers was palpable.

When I sat for my religion O-Level exam I remember being told that unless my essays came to the “right” conclusion, I would fail. Without that O-level I couldn’t attend University, so I had to comply.

Sitting in my philosophy class in Junior College (admittedly on one of the rare occasions I chose to attend class) I was told that unless I came to the same conclusions in my argumentative essays as the authors whose books I had to read for the course, I risked failing the subject altogether.

I remember taking a look around during a Systems of Knowledge lecture and recognising that

few really appreciated the importance of ‘Pericles’ Funeral Speech’ and its parallels with Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Only a handful of those present were in any way enthusiastic as the lecturer discussed Plato’s Allegory of the Cave – most were nodding off in their chairs, clearly drained by the effort of trying to reconcile the metaphorical language of Ancient Greece with the literalism that had thus far shaped their world growing up.

Can you blame them? Not really. They’d been taught for most of their developing years that their task was not to genuinely question or interrogate authority in the interest of real, progressive debate. They were meant to toe the line. They learnt by rote, they memorised.

They ingested knowledge as something to be reproduced according to strict guidelines and practices, which is perhaps why the country has produced so many doctors, lawyers and priests.

Is it any wonder, then, that the debate around a memorial for a slain journalist is what it is today?

Many Maltese do not realise that to stamp out the flowers and tear off the photos at the ad hoc memorial is fascism, defending it instead as their own form of “free speech”. When did silencing others become “free speech”?

They qualify their actions by describing the memorial as “vandalism” of a national monument – a monument that commemorates the united Maltese victory against those who would enslave them; a fitting backdrop for the memorial of a fallen member of the fourth estate.

And if the fact that it is “national” justifies this kind of behaviour, then the streets of Valletta are a national space too – but if one minority wants to peacefully protest there and the government or its followers try to silence those protestors, that’s not free speech.

Fascism is defined as a governmental system led by a leader having complete power, forcibly suppressing opposition and criticism, and emphasising an aggressive nationalism and often racism. Ring any bells?

Trump calls the media and protestors enemies of America. Trump, his supporters, and the alt-right have made an entire political agenda off of making their adversaries out to be a threat. So too, did the Labour Party with Daphne Caruana Galizia. So too, the Labour Party with those citizens who insist on calling for justice when all the Party in government wants to do is to bury the news and move on.

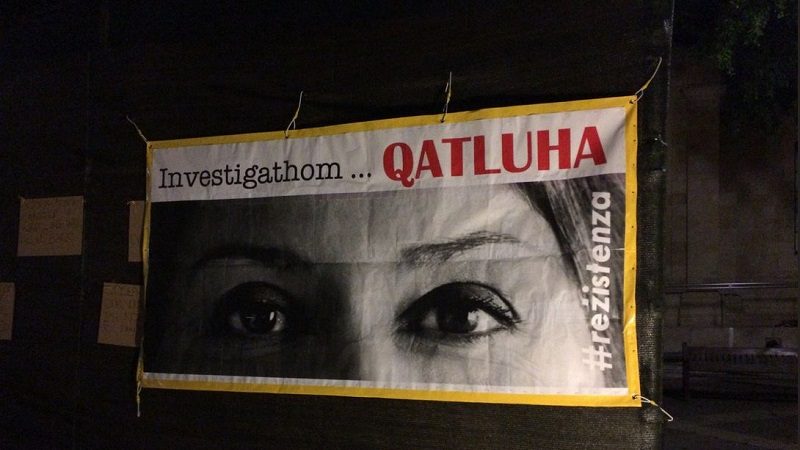

Remembering her name and standing up to those who want her forgotten has become an act of resistance.

A vigil will be held to mark the day of Caruana Galizia’s assassination on Sunday 16 September at 7pm at the Great Siege memorial.