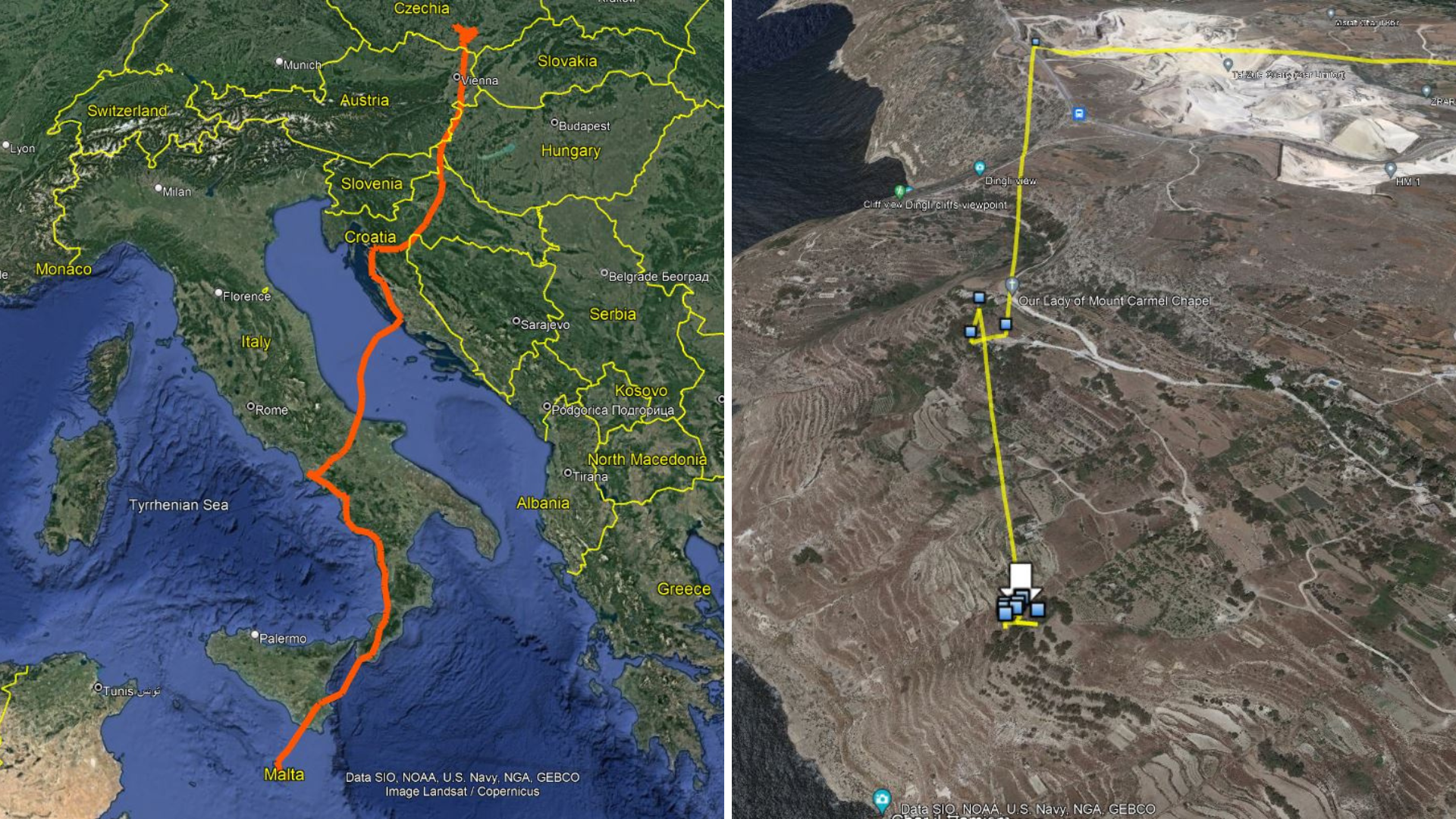

Hundreds of thousands of euros of member state funds are being wasted due to hunting in Malta, a practice allowed to increase in violation of EU rules and abetted by the government to “secure the votes of the hunting lobby”, according to new cross-border research conducted by The Shift and international partners.

Hunters have been given a “free for all” through increasingly lax regulations and consistent lack of enforcement, in return for their vote according to conservationists interviewed by The Shift’s research partners. These measures ignore the impact on conservation efforts in Europe, they added.

German state officials who spoke to The Shift’s partners estimated that for just a single bird species, conservation efforts cost €500,000 per year.

Hunting in Malta was described as a “way of life” and a “god-given right” in interviews conducted by The Shift with representatives of the local hunting lobby.

The practice indiscriminately tarnishes bird populations across Europe as shot birds are tracked as originating from different member states and environmentalists claim it “wastes away” costly and time-intensive conservation efforts undertaken by other EU countries.

Furthermore, hundreds of thousands of euro invested annually by countries such as Germany in conserving various bird species are squandered to appease the circa 10,000 Maltese hunters who annually apply for seasonal hunting licences.

An intolerable situation

Throughout a short spring season and a five-month-long autumn season spanning from September to January, some 10,000 hunters go after various bird species, many of which are subject to dedicated and expensive conservation programmes in the EU.

Dr Norbert Schäffer, Chariman of the German nature conservation association LBV – Photo: Thomas Krumenacker

Dr Norbert Schäffer, chairman of the German nature conservation association LBV, told The Shift’s German partner, environmental journalist Thomas Krumenacker: “It is intolerable that birds helped in one European country are then illegally shot in another country, part of the same EU”.

He said that in other EU countries, “there is certainly the desire and the will to curb illegal hunting, but as far as Mediterranean countries, especially Malta, are concerned, I am sceptical whether this is meant seriously”.

“In Malta, the problem has been known for a long time, and it is a relatively small area to enforce, so I would expect that the Maltese government would get a grip on it,” he said, adding this “suggests that authorities are not serious”.

“It is completely demotivating to witness a bird shot without consequence, maybe a bird which one knows personally, which one has ringed,” he added.

The Montagu’s Harrier has conservation efforts in Germany which amount at least €500,000 per year – Photo: Thomas Krumenacker

Joseph Tumbrinck, special representative for the National Species Recovery Programme at the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, said that conservation efforts for just one raptor species, the Montagu’s Harrier, can cost “at least €500,000 per year”.

Tumbrinck echoed Schäffer’s remarks and noted that countries along birds’ migratory routes, such as Malta, pose a threat which increases with the species’ rarity as shooting rarer birds proportionally pose a greater risk due to the smaller populations.

Montagu’s Harrier chicks are saved in Germany from natural or man-made threats through costly conservation programmes – Photo: Alex Heydt

A two-pronged issue

Malta faces annual controversy with the opening of a spring hunting season, breaking EU law in the process.

The EU Birds Directive bans the practice of spring hunting due to its impacts on migrating bird populations, but despite this, a 2015 referendum confirmed public support for the practice by a slim margin.

Spring hunting is particularly harmful as it coincides with bird species’ northerly migration for breeding, amplifying its negative impact on their populations.

In 2015, the IUCN placed the European Turtle Dove on its Red List of threatened species, classifying it as vulnerable to extinction with the Maltese government placing a moratorium on Turtle Dove spring hunting in 2017. But this decision was then overturned by Prime Minister Robert Abela just weeks before the 2022 general elections.

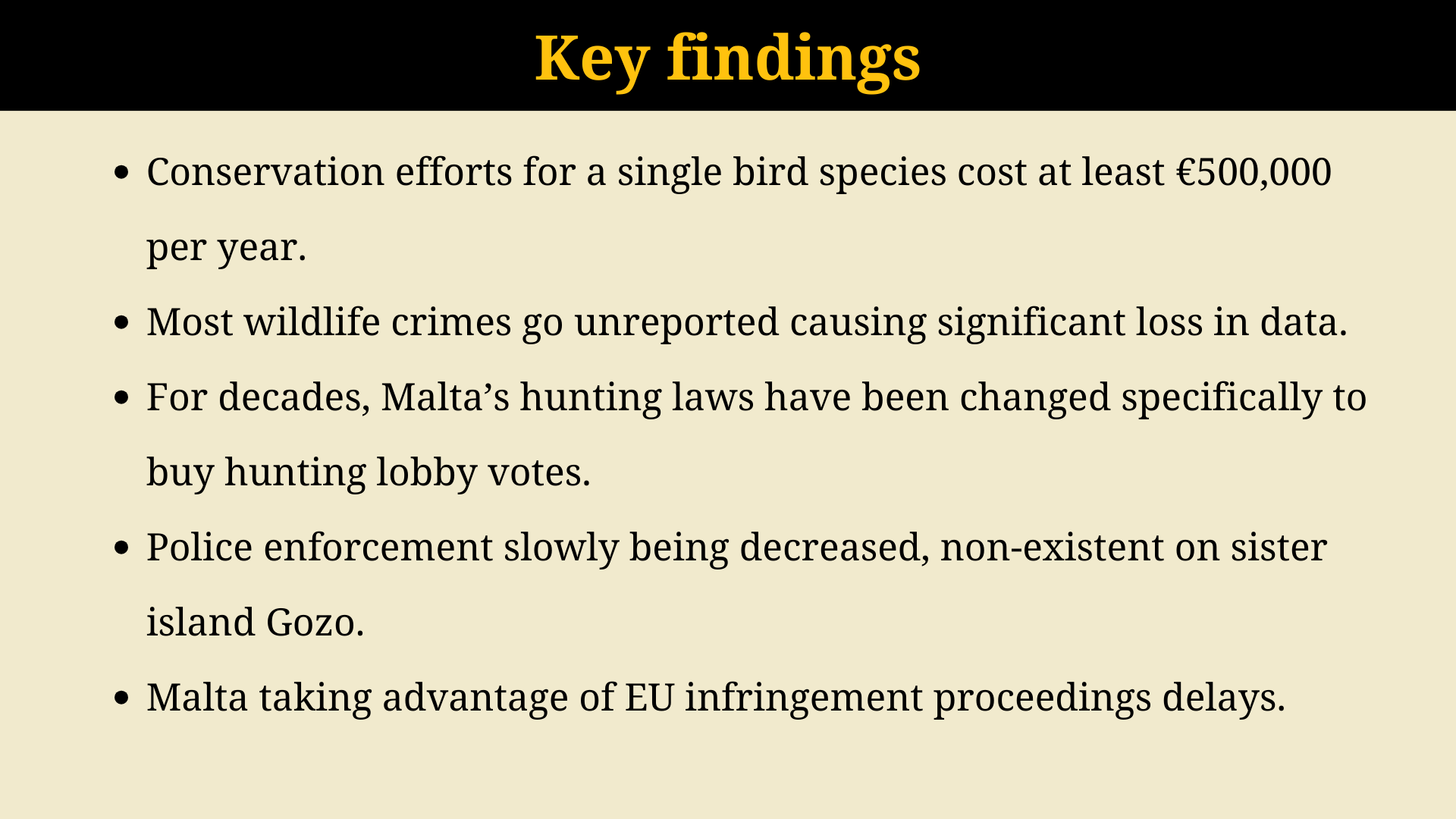

While Maltese hunters shoot down many bird species, only a few are legally allowed to be hunted – Photos: Thomas Krumenacker and Birdlife Malta

The opening of hunting seasons in autumn and spring is only one side of a two-pronged issue, as legal hunting seasons for some bird species subsequently lead to the illegal hunting of legally protected bird species.

In comments to The Shift, BirdLife Malta’s Head of Conservation, Nicholas Barbara, said illegal hunting disproportionately impacts those bird species more at risk, given they are sought after for their relative rarity.

“Poachers who illegally hunt protected bird species place a higher prize on shooting down a rare bird. The rarer the bird, the more ‘valuable’ it is perceived to be,” he said.

Hunting: ‘a god-given right’

In response to The Shift’s questions about the hunting lobby’s views, the Hunting Federation (FKNK) CEO Lino Farrugia said, “The phrase ‘illegal hunting’ has no significant meaning. We [the FKNK] practice legal hunting while, unfortunately, some, as in other spheres of life, commit illegalities”.

Farrugia claimed “the number of illegalities attributable to hunting has been reduced to a few dozen yearly,” chalking up the improvements to FKNK’s educational campaigns and “the present government’s genuine help”.

He said, “Our country’s illegalities are under control as they are in any other European country,” and he contested the characterisation of hunting as “a hobby”, calling it a “passion and a way of life.”

He added, “Through a god-given privilege, the hunter and the trapper can enjoy nature at its best, which they work to preserve with such dedication” and “This lack of privilege in environmental conservation organisations results in jealousy and spite against hunters and trappers.”

“In Malta, birds are hunted in such small quantities that it does not affect any species’ populations, both legally huntable and those protected,” he claimed. Farrugia said this made hunting “sustainable”.

Farrugia’s comments contrast with those of conservationists who spoke to The Shift.

CABS’ Axel Hirschfeld taking part in conservation work alongside Montagu’s Harrier chicks earlier this year – Photo: CABS

Committee Against Bird Slaughter (CABS) press officer Axel Hirschfeld said “sustainability” is “the most raped word in conservation history”.

Barbara, from BirdLife Malta, said, “This year has seen a resurgence in the illegal hunting of birds of prey”.

BirdLife Malta CEO Mark Sultana added that “protected birds are being killed every day, continuously” in a statement last September following the killing of an Osprey born and ringed for study in Latvia last July, ahead of its first migratory flight to Africa.

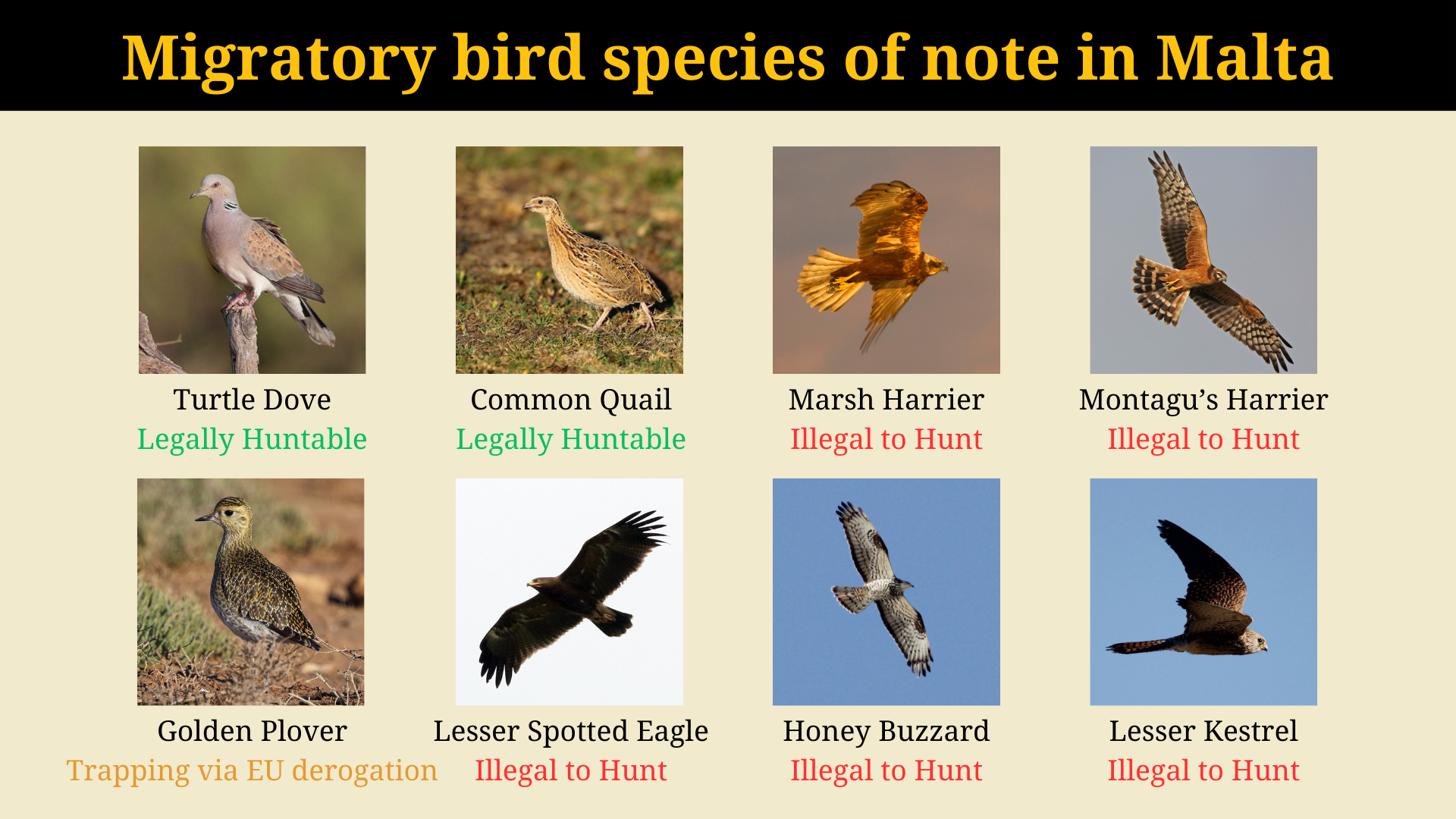

BirdLife Malta later issued data showing how birds of prey, a Black Kite and a Honey Buzzard, being GPS-monitored as part of conservation efforts, suddenly stopped sending signals as soon as they flew over Malta.

They are suspected to have been shot dead, and their GPS receivers, which tracked their flights spanning multiple countries, are believed to have been destroyed upon retrieval by poachers.

The Black Kite, OT-093, stopped transmitting over Fawwara, its long journey from the Czech Republic cut short – Photo: BirdLife Malta

The issue is historic, evidenced by many earlier incidents, such as the shooting of a Lesser Spotted Eagle several years earlier, itself part of a German conservation effort which cost more than €1 million.

Over just the first two months of the Autumn 2023 hunting season, BirdLife Malta has noted the illegal shooting of Ospreys, Flamingos, Honey Buzzards, Marsh Harriers, an Egyptian Vulture, a Booted Eagle, a Short-Toed Eagle and Lesser Spotted Kestrel.

The Shift asked FKNK to join them in the field during the autumn hunting season, but the association refused and instead suggested conducting interviews on private land during off-peak hunting hours.

An ‘intentional’ staging ground for illegalities

The Shift’s journalists joined BirdLife Malta in the field on observational sessions in this year’s spring and autumn hunting seasons, during which volunteers scout the island’s countryside for illegalities, unofficially boosting the government’s poor police presence.

Data provided by BirdLife Malta shows that for this year’s spring hunting season, 65% of shot, recovered birds were retrieved by BirdLife Malta’s teams rather than official government agencies.

Their records show that over the spring season, BirdLife Malta encountered police presence at a maximum of 5% of the prominent hunting locations monitored.

In an interview with The Shift in the spring, Barbara noted that opening a spring season for Quail and later Turtle Dove meant other protected birds could be easily targeted.

He also highlighted the issue of birds being killed in Malta being “taken away from other European countries,” adding it “undermines all the conservation efforts that are being done.”

In a follow-up interview this autumn season, Barbara described how police enforcement had been further reduced, as the usual number of officers delegated to aid the Environmental Protection Unit had not been dispatched.

He said 2023 “has been one of the worst years in terms of police presence”.

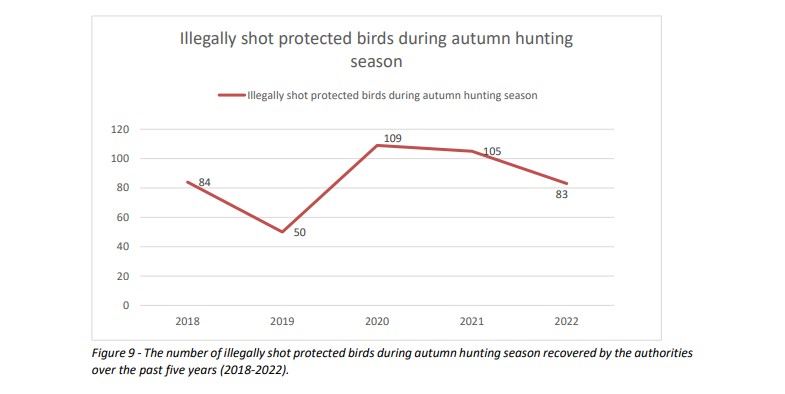

Data published by the government’s Wild Birds Regulations Unit, the government hunting licensing and regulatory body, shows that targeting protected birds remains a significant issue.

The report, which noted the illegal hunting of 83 protected birds in the autumn 2022 season alone, said, “The problem of illegal killing of protected birds (IKB) is still evident, and thus the issue continues to merit the urgent attention of all stakeholders at national level since there is a much-needed concerted effort to actively curb IKB-related crime.”

A WBRU report on last year’s autumn hunting season, deemed to be conservative, shows that almost 100 protected birds are recorded shot each Autumn.

Several conservationists who spoke to The Shift agreed that actual figures are likely to be higher and that the trend of illegal shootings is increasing with the decline in enforcement.

95% of wildlife crime ‘unreported’

In an interview with The Shift last May, Committee Against Bird Slaughter (CABS) press officer Axel Hirschfeld noted the importance of accounting for the unreported instances of such wildlife crime, referred to as the ‘dark figure’.

He concluded with the sobering observation that “with this kind of wildlife crime, you have to assume a dark figure of at least 95%, essentially multiplying every reported crime 20 times for a more accurate idea of the reality”.

Hirschfeld confirmed that illegal hunting in Malta is a significant issue for foreign conservation efforts as “Malta might be a small country, but it lies centrally on one of the most important migratory routes.”

He said species such as Montagu’s Harriers, “are essentially totally dependent on conservation efforts to survive – these same birds are being targeted in Malta. We have had several incidents of large roosts being shot in the night,”

Commenting on the same issue, Barbara noted several changes introduced to Malta’s hunting laws and policies over the years, making the illegal hunting of protected birds easier “on purpose,” to secure the votes of the sizeable number of licensed hunters.

He said the ultimate aim for poachers who shoot down protected bird species is taxidermy.

Lifting of hunting curfews

In 2013, upon the election of the Labour party in government, autumn hunting curfews were extended from 3pm to 7pm.

The move was widely criticised since legally huntable species, like Quail and Turtle Dove, generally migrate at night and are widely hunted in the hours before dawn.

Meanwhile, afternoon hours are when birds of prey, all protected species and concurrently the most coveted trophies for illegal hunters, fly low and roost.

Barbara said the lifting of the curfew allows hunters to be in the countryside with the excuse of hunting legal species at a time when migratory protected species come to roost.

Downsized and lax police enforcement

A shot Marsh Harrier held by a member of the Malta Police Force earlier this year – Photo: CABS

The issues created by the legislative amendments are compounded by lax and inconsistent enforcement by the Malta Police Force’s Environmental Protection Unit (EPU).

Over several days in which The Shift joined BirdLife Malta on observational tag-alongs, during both the spring and autumn hunting season, only one EPU unit was ever encountered.

A report by the Wild Birds Regulation Unit shows that during the autumn 2022 hunting season, 18 EPU officers were complemented by 41 officers coming from district police, Gozo police, Environmental Rangers, the Armed Forces of Malta and the WBRU itself for a total of 59 officers.

This year, the additional manpower was conspicuously absent. BirdLife Malta claimed the EPU “currently numbers only 15 officers that operate on a shift basis.”

“This means that during peak migration events, a maximum of 1-2 police units specialised on hunting matters were operative on Malta,” they said, with environmental specialised units “non-existent” on the sister island, Gozo.

The Malta Police Force has refused to answer The Shift’s questions for more information on enforcement and the number of units available.

Analysis by The Shift of data from the WBRU yearly reports on enforcement shows a slow but steady decrease in the average number of deployed officers.

The data shows the maximum and minimum number of enforcement officers deployed daily for a given period. The Shift’s analysis extrapolated trendlines from the WBRU data, showing the gradual decrease in on-the-ground enforcement.

The daily number of deployed officers fluctuates throughout the autumn hunting season, resulting in prominent peaks in the data. Nevertheless, trendlines (dotted) show a slow but steady decrease in on-the-ground enforcement.

Keeping ‘what’s ours, ours’

Gozo Minister Clint Camilleri, a hunter and a trapper himself, has been controversially handed the hunting portfolio since 2017, detaching the responsibilities from the Environment Ministry.

BirdLife Malta had called the move “diabolical” and “purely electoral”.

In parliamentary comments at the time, Camilleri said, “Our position to safeguard [the hunting] tradition is very clear”.

Reiterating his promise during the 2022 electoral campaign Camilleri vowed to his constituents to “keep what’s ours, ours”.

Gozo Minister Clint Camilleri told constituents during the 2022 electoral campaign that when it came to the hunting issue, he would “keep what’s ours, ours.”

The EU’s ‘slow wheels of justice’

Malta is currently facing two active infringement proceedings by the European Commission.

The first proceeding, related to Malta’s ‘research’ derogation for trapping of finches, is now being heard before the European Court of Justice.

The second, more general proceeding, is related to Malta’s failures in enforcement and creating a general system of protection for wild birds.

A second letter of formal notice was issued in February of this year, ahead of the spring hunting season.

European Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius condemned Malta’s decision to open a spring hunting season for Turtle dove, expressing his “deepest concerns” in a letter to Camilleri.

During a visit to Malta last July, he said the EU “had no choice” but to take action following Malta’s refusal to comply with its directives.

Sinkevičius said Malta’s decisions do not just have a local impact but go against “the collective and dedicated efforts of the Commission, member states and stakeholders to halt the population decline and begin the recovery of the species.”

Since joining the EU, Malta has faced six different infringement cases for its breaches of EU law regarding hunting and trapping.

Commenting on the never-ending stream of formal letters, reasoned opinions and court cases, CABS’ Hirschfeld said, “The Maltese government thinks year to year. If they can create another derogation and ‘save themselves’ until re-election before facing any consequences from the EU, they will.”

He said ignoring the illegal killing of protected birds and legalising the killing of endangered species such as Turtle Doves through derogations is nothing but “the Maltese government taking advantage of the EU’s slow wheels of justice”.

Additional research and reporting by Thomas Krumenacker.

Editing by Caroline Muscat.

This article was brought to you with the support of IJ4EU and is part of a series involving cross-border investigative journalism.

The level of skill involved is at least fundamental – sending a spray of shot in the general direction of a target requires minimal animal reflex impulses.

I had a ‘hunter’ as a friend – his stories and ‘passions’ he deemed relatable – with photos.

In the US, with its vast spaces and fauna, hunting is both popular and regulated. In the UK – much less so. In Malta – ‘hunting’ is reduced to taking pot-shots at tired and vulnerable migratory birds.

And all of this to keep a corrupt and criminal element out of prison.