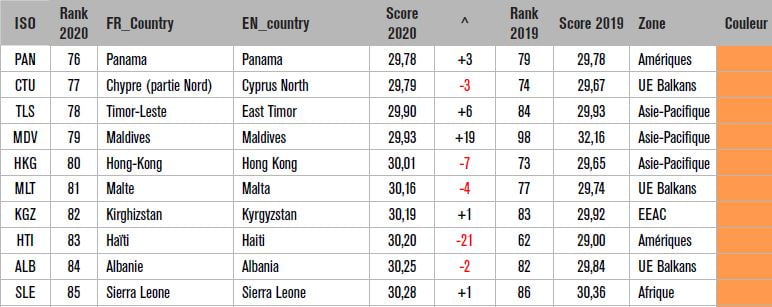

Malta’s ranking in the World Press Freedom Index continued to fall, dropping another four places after it plunged 30 places in the previous two years.

The country now ranks 81, categorised in the annual global index by Reporters Without Borders as ‘problematic’.

The annual report, released on Tuesday, says journalists working in Malta “are coming under intense judicial pressure”.

Malta’s new score now sits directly beneath that of Hong Kong and above that of Kyrgyzstan and Haiti, which was singled out in the Index as suffering one of the “biggest declines” in press freedom rankings, dropping 21 places. Haitian journalists have often been targeted during violent nationwide protests over the past two years.

Malta’s ranking in the Index has consistently dropped since 2013, when the country ranked 45.

The country’s ranking took a blow following the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia by a car bomb in October 2017, and continued to slip as doubts on the investigation and delays by the government stalled justice amid concerns voiced by a number of European institutions on the rule of law.

Malta lost 12 places in the 2019 Index, a drop that followed 18 places lost in 2018 – the report for the year of Caruana Galizia’s death. Over the last three years alone, Malta lost 34 places in its press freedom ranking.

The report refers to “country progress in the fight against impunity for violence against journalists in Slovakia and Malta” – two EU countries were journalists were murdered because of their work.

While noting that progress was made in the two countries on the murder investigations, Slovakia’s ranking increased for the first time in three years (two places), yet Malta continued to slip.

The report noted that “the investigation into the murder of the journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia is finally making progress, although journalists there are still coming under intense judicial pressure”.

Malta ranks 81 out of 180 countries in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index.

The Index, an annual report of the state of journalism in 180 countries, also highlighted the effect of coronavirus on journalism. “The coming decade will be decisive for the future of journalism, with the COVID-19 pandemic highlighting and amplifying the many crises that threaten the right to freely reported, independent, diverse and reliable information”.

The next 10 years will be pivotal for press freedom because of five converging crises that affect the future of journalism. These range from geopolitical issues, where dictatorial or populist regimes try to suppress information and impose their visions of a world without “pluralism and independent journalism”, to technological challenges that create a situation where “propaganda, advertising, rumour and journalism all come in direct competition”.

“The digital transformation has brought the media to their knees in many countries,” the Index pointed out in reference to the economic crisis. Decreasing sales and advertising revenue and an increase in production and distribution costs have forced news organisations to restructure and lay off journalists.

The launch of the 2019 World Press Freedom Index in London with (from right) The Shift’s founder Caroline Muscat, Turkish journalist Erol Onderoglu, RSF UK Bureau Head Rebecca Vincent and John Fraher from Bloomberg.

The Index also highlighted a democratic crisis that “has now worsened” and said there was growing hostility and, even hatred, towards journalists over the past two years. This has led to more serious and frequent acts of physical violence and, therefore, an unprecedented level of fear in some countries.

“We are entering a decisive decade for journalism linked to crises that affect its future,” RSF Secretary-General Christophe Deloire said.

“The coronavirus pandemic illustrates the negative factors threatening the right to reliable information, with the pandemic itself an exacerbating factor. What will freedom of information, pluralism and reliability look like in 2030? The answer to that question is being determined today,” he said.

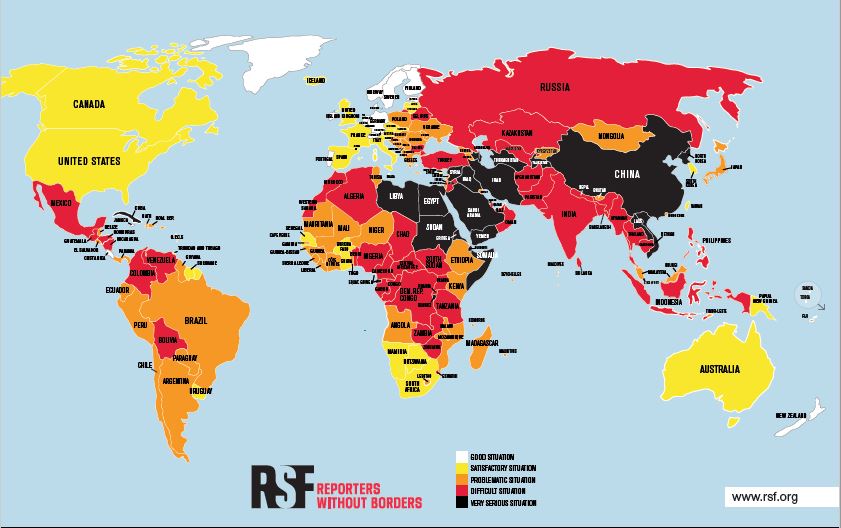

In fact, the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has been used by several governments to suppress media freedom and this was reflected in the index rankings. Both China, which is in 177th place, and Iran, which dropped down three places to 173, censored the coronavirus outbreaks in their countries extensively.

In Iraq (down six places at 162), the authorities stripped international news agency Reuters of its licence for three months after it published a story questioning official coronavirus figures.

RSF Press freedom map

This has also been taking place close to home. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán just had a coronavirus law passed with penalties of up to five years in prison for false information, which was “a completely disproportionate and coercive measure,” the report said.

“The public health crisis provides authoritarian governments with an opportunity to implement the notorious ‘shock doctrine’ – to take advantage of the fact that politics are on hold, the public is stunned and protests are out of the question, to impose measures that would be impossible in normal times,” Deloire added.

For things to change, the call must come from society, the report stresses.

“For this decisive decade to not be a disastrous one, people of goodwill, whoever they are, must campaign for journalists to be able to fulfil their role as society’s trusted third parties, which means they must have the capacity to do so,” he said.

Norway tops the Index for the fourth year in a row in 2020, while Finland is again the runner-up. Denmark took Sweden’s spot at third place as the Nordic country, and the Netherlands slipped down from last year’s rankings as a result of increases in cyber harassment.

#RSFIndex ¦ RSF unveils its 2020 World Press Freedom Index:

1: Norway🇳🇴

2: Finland🇫🇮

3: Denmark🇩🇰

11: Germany🇩🇪

34: France🇫🇷

35: United Kingdom🇬🇧

45: United States🇺🇸

66: Japan🇯🇵

107: Brazil🇧🇷

142: India🇮🇳

166: Egypt🇪🇬

178: Eritrea🇪🇷

180: North Korea🇰🇵https://t.co/4izhhdhZAo pic.twitter.com/biJfunlTSw— RSF (@RSF_inter) April 21, 2020

The other end of the Index has seen little change. North Korea is now the worst ranked country for press freedom at 180, replacing Turkmenistan.

The biggest risers in the 2020 Index were Malaysia, which moved 22 places to 101, and the Maldives, which gained 19 points to 79th place. The increase came about thanks to the beneficial effects of changes of government through the polls, according to the report.

The Index pointed out that Europe still “continues to be the most favourable continent for media freedom, despite oppressive policies in certain European Union and Balkan countries”.

RSF said press freedom was high on the agenda of the new European Commission, in line with the organisation’s recommendations published during the campaign for the 2019 European elections.

“Europe was shaken by a series of serious abuses, including murder, carried out against journalists and now is the time for it to focus on the battle for press freedom,” it said.

It welcomed the action plan presented by European Commission Vice-President Vera Jourová, which provides for strengthening media freedom, making social networks more accountable and protecting the democratic process.

But the NGO said it was “regrettable” that the EU enlargement portfolio, which was crucial for integrating the countries of the Western Balkans, was attributed to the Commissioner from Hungary, one of the EU’s most repressive governments.

You can read the report in full here.