Mark Anthony Falzon insists that press freedom in Malta is not under any more threat now than it was five years ago.

According to his recent Times of Malta opinion piece ‘Reporters without Arguments’, he doesn’t think the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) World Press Index captures the situation in Malta, either.

But there are two obvious differences between 2014 and 2019.

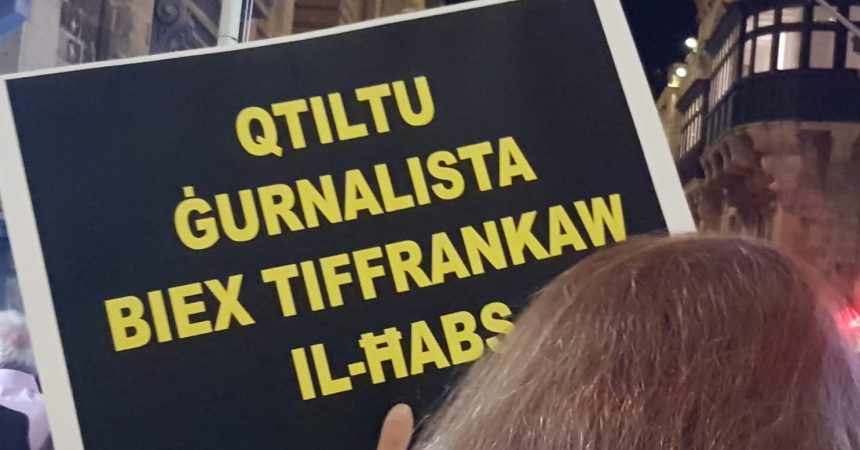

Daphne Caruana Galizia was assassinated with a massive car bomb after investigating and writing about corruption at the highest levels of government. A journalist had never been murdered in Malta before 2017.

The other difference is the complete impunity enjoyed by those who were exposed by Caruana Galizia’s investigations. So many damning details have come out — enough to prompt resignations in any other Western democracy, and in several cases enough to result in criminal charges followed by serious jail time. None of these public officials have been held accountable in Malta.

Instead, civil society activists who call for an end to impunity have been harassed, whistleblowers have been persecuted, and journalists — including Caruana Galizia and The Shift — have been hit with frivolous lawsuits and SLAPP campaigns designed to silence their stories.

Falzon does not believe any of these things are threats to press freedom. Rather, he’s convinced that journalism and online trolling are both healthy expressions of free speech. “If Reporters Without Borders believe that cyber harassment is a threat to press freedom,” he writes, “they have no choice but to think the same of Daphne’s work.”

This is a ridiculous assertion. I’ll spell out the difference in simple terms. Journalists report on facts. Organised troll factories attempt to silence those stories.

The cyber harassment and trolling referenced in the World Press Freedom Index is organised by the political party in power, and it is being used to target anyone who opposes that Party. Politicians, including top government officials, were proven to be members of closed Facebook hate groups, where the personal details of anti-corruption activists were shared, along with calls for them to be physically attacked, sexually assaulted and stalked.

Does Falzon really place such intimidation on the same level as investigative journalism?

Would he also defend Cambridge Analytica’s use of organised disinformation campaigns to manipulate elections? How are organised intimidation campaigns aimed at discouraging dissent any different?

Falzon believes the World Press Freedom Index is useless because such indexes “are reductionist, and they gloss over local history and political culture”.

Perhaps he’s been blinded by a “local context” where attacking anyone who criticises the government has been normalised. Coordinated online hate campaigns are the modern version of burning down the Times of Malta and smashing up the Opposition leader’s home. It’s mob rule.

While Malta’s bitter political divide, and its predilection for nepotism, cronyism and ‘persons of trust’ did much to create an atmosphere where journalists are routinely sued into silence by government ministers, property developers, consultants to criminals, and banks, they do nothing to absolve the government from its legal responsibility to protect the lives of all its citizens — even the critics it really, really hates.

Falzon claims an independent public inquiry into Caruana Galizia’s death would be “a waste of time and money”. But when the State fails its responsibility to protect the right to life, there is a legal obligation to find out why. This is clearly detailed in Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Given the rampant state of corruption in Malta, the implications of an inquiry into whether Caruana Galizia’s assassination could have been prevented are clearly disturbing.

One of the accused killers, George Degiorgio, was under surveillance by the security services at the time of her death. The Agency reports directly to the Prime Minister. Did the government know in advance that Caruana Galizia would be killed, but did nothing to prevent it?

Why have none of the politicians she wrote about been questioned — especially Economy Minister Chris Cardona, who was reported speaking to accused killer Alfred Degiorgio both before and after the journalist’s assassination?

Did the climate of hate stirred up by closed Labour party Facebook groups — the very same hate groups Falzon defends in his article — contribute to the creation of a political climate in Malta where a journalist could be killed with impunity?

These are the questions that need to be answered, and they have nothing to do with taking into account “the local context”.

But Falzon doesn’t stop with minimising the legitimate concerns of one of the world’s most reputable press freedom organisations. He also seeds his article about this year’s Index with outright misrepresentation, stating, “Journalists, we’re told, live in terror, especially in the aftermath of the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia”.

No, in fact, we weren’t told that at all.

But we were told, in very clear terms, why Malta plummeted another 12 places in the 2019 press freedom rankings (and a total of 32 places since Joseph Muscat’s government came to power in 2013).

Falzon can’t see any cause for concern, and he can’t see what the government’s daily removal of candles and flowers placed by activists in Valletta has to do with press freedom, either.

What exactly would meet his lofty criteria? Anything short of being physically silenced, or hauled off to a gulag?

Muscat and his inner circle view these peaceful protestors as their personal opponents, along with journalists who actually do their jobs rather than regurgitate canned government press releases verbatim. Critics of the government are labelled “traitors to Malta” — as though the Labour Party and the nation were the same thing. It’s all part of discouraging civil dissent.

None of this is conducive to press freedom in Malta.

It surprised me to see Falzon brush these things aside. Then again, few academics need to check beneath their cars before driving away, and even fewer need to worry about being targeted by organised groups that are backed by the government. No one’s ever been assassinated for writing detailed studies of consanguinity, or for chairing committees that rubber stamp government decisions for that matter.

Falzon’s assessment of RSF World Press Freedom Index was naive at best, and disingenuous at worst. But it was towards the end of his article that he made his most offensive assertion. According to this noted academic, Caruana Galizia “was happy to risk her life rather than have her journalistic work compromised”.

Is writing one’s truth really something which should require risking one’s life?

Press freedom will continue to erode in Malta as long as journalists who are critical of the government are physically threatened and harassed with frivolous libel suits.

Today is World Press Freedom Day, but the only thing that surprised me about this year’s RSF World Press Freedom Index is that Malta didn’t fall further.