When we read or watch the news, it is usually the political leaders of the world that we see posturing, shaking hands, awkwardly avoiding eye contact or warmly patting each other on the back.

We can therefore be forgiven for thinking that it is French President Emanuel Macron, Supreme Leader of North Korea Kim Jong Un, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Hungarian President Viktor Orbán or Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat who take the final decisions and who are in complete control over their respective nations.

In reality, however, no leader is monolithic and no leader, regardless of where he or she lies on the political spectrum, has absolute authority. Once we part with this idea, then the logic of politics is surprisingly simple. The only thing that changes according to authors Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith is how many backs need to be scratched in order for a leader to stay in power.

For a potential leader, the political landscape can usually be broken down into three groups. These are: the nominal selectorate, the real selectorate and the winning coalition. Let’s look at what each term means.

The nominal selectorate is the pool of potential support for a leader. In Malta, this is every individual who is eligible to vote.

The next layer is the real selectorate whose support is influential in so far as this is the group that actually chooses the leader. In Malta, this would be the elected Members of Parliament from the majority Party.

The most important group, however, is the third, which is just a subdivision of the real selectorate that form what the authors call a winning coalition. These are the leader’s essential supporters without which he or she would not survive. On our little island these are likely to be a handful of ministers (perhaps those that have somehow weathered their respective scandals) senior civil servants or “persons of trust” without whose support Muscat would have been shown the door.

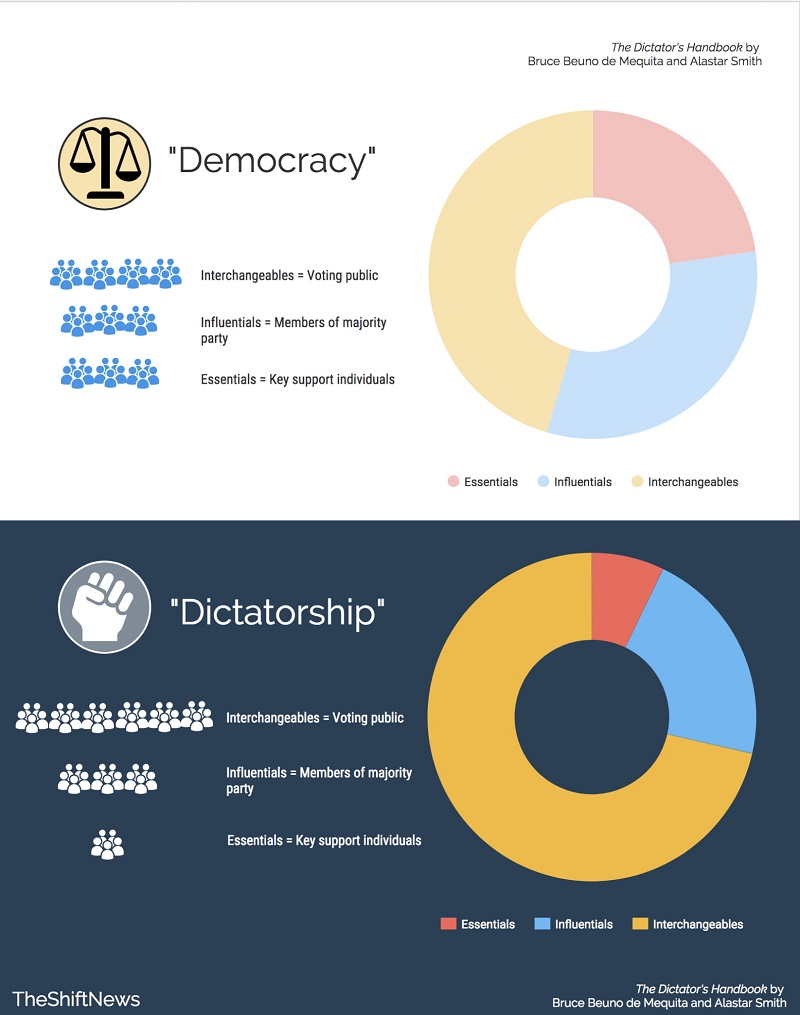

Another way to view these groups is as: interchangeables, influentials and essentials. These three groups provide the basis for the rest of the book because Bueno de Mesquita and Smith believe that these same groups are at the heart of all the political machinations, whether of a State, a corporation or a small family business.

What is particularly interesting is that the variations in size of these groups determine almost everything that happens in politics – what a leader can and cannot do, what he or she can get away with, to whom they answer and the quality of life enjoyed (or not) by those they rule over.

If it’s all beginning to sound a little tricky – that’s because it is. For those of us who are not the authors of this book, our daily experience of politics tells us that just three layers is a little reductive, isn’t it? After all, political pundits tell us what lies at either end of the political spectrum.

On the one hand we have autocrats and dictators – cruel, selfish individuals and the occasional psychopath. On the other we have democrats, elected leaders safeguarding our freedoms. Surely there is an enormous difference? Well, not really. What ultimately differs across these types of governments is simply the sizes of these three groups and how they interact with one another.

Presented this way, even the labels ‘democracy’ and ‘dictatorship’ are no longer enough to explain differences between regimes. This is also in part because no two democracies are the same and neither are two dictatorships, and this variety stems from people’s incredible ingenuity at manipulating politics to work to their advantage.

The same is, of course, true to labels which political parties give to themselves. Even the Nazi Party was supposed to be a ‘socialist’ party – a national socialist party. There are as many varieties to a political label as one wishes.

Therefore, what the authors want to emphasise when they speak of democracy is simply a government founded on a very large number of essentials and interchangeables, with the influential group being almost as big as the interchangeable group.

A dictatorship is a government that is based on a particularly small number of essentials drawn from a large pool of interchangeables and often a small number of influentials. Still confused? Here’s a handy infographic:

Is there any benefit in talking about politics using these terms apart from sounding a little pompous? Yes, the first is that using these terms stops us from drawing an arbitrary line between forms of government and labelling one as democratic and the other as autocratic.

After all, we have examples in history of “kings” that were elected and plenty of current examples of “democrats” who rule their countries with the heavy hand of a despot.

Moreover, thinking of political behaviour in these terms helps us better understand that even a slight change in one of these group variables changes the leader’s incentives and consequently the leader’s behaviour. And it is our leaders behaviour that we are trying to better understand, especially when it appears to be at odds with facts presented to us.

Managing the interchangeables, influentials and essentials to retain as much power for as long as possible is, as the authors put it, “the act, art and science of governing”.

Read more in the series: The Dictator’s Handbook

Source: The Dictator’s Handbook: Why bad behaviour is Almost Always Good Politics by Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith.