Money laundering is what makes crime profitable. Without laundering their illicit gains, criminals wouldn’t be able to enjoy the proceeds of their illicit gains, and to finance further crime.

Criminals need to convert the illicit cash they have made off their victims into funds having a legitimate appearance without arousing suspicion, and in a way that the origin of the cash is concealed. That is money laundering.

The Panama Papers have shown how financial structures can be set up with the “ultimate beneficial owner” (UBO) remaining anonymous, the source of the funds concealed, and the capability to transfer funds without leaving an audit trail.

The Panama Papers also showed that trust offices and relevant practitioners do not always perform their obligations adequately, and that offshore companies often falsify or tamper with documents.

No one would have ever found out about minister Konrad Mizzi and the Prime Minister’s chief of staff Keith Schembri’s secret companies, and that the two were to receive €150,000 monthly through these companies had it not been for the Panama Papers revelations.

No one would have found out that some documents related to the offshore companies held by Mizzi and Schembri, were forged and that Mizzi gave instructions to Nexia BT to backdate documents to cover his tracks, were it not for a leaked FIAU document revealing all this.

No one would have found out that Mizzi and Schembri’s companies were not worth €92, as Mizzi had repeatedly claimed, but €9,200. In fact not even the “independent auditor” commissioned by Mizzi to audit his financial affairs managed to ferret this out. Of course, auditors rely on the information given to them for their evaluations.

That is why it is of paramount importance to uncover who is behind the mysterious Dubai-registered company, 17 Black, which was set to be a “target client” for Mizzi and Schembri’s companies.

The Daphne Project published evidence that Mizzi and Schembri’s Panama companies were destined to receive €150,000 monthly from a secret Dubai company named 17 Black and another “target client” called MacBridge.

FIAU investigators did not manage to uncover information about the people behind 17 Black and MacBridge but a $1.4 million payment to 17 Black from a Seychelles company owned by an Azerbaijani national was traced.

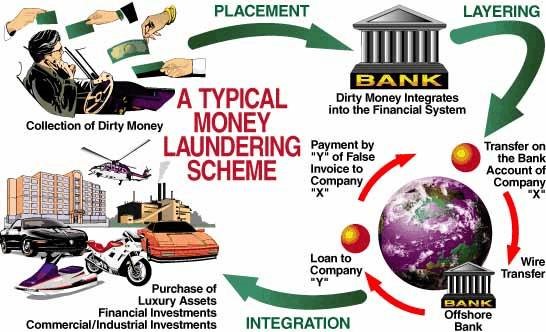

Money laundering nowadays is highly sophisticated and complex, involving webs spanning multiple borders and using several schemes and techniques, and multiple entities.

Cash transactions remain one of the predominant instruments of money laundering.

Cash offers anonymity and is difficult to audit. Money launderers often deal in high value goods in cash, such as real-estate, jewellery, antiques, paintings, and cars, involving their illicit funds in the transactions until these funds have a semblance of legitimacy and their origin can no longer be established.

There are due diligence and reporting obligations on any cash transactions above a certain value, mainly on the source of the cash, but the origin of funds is often hard to determine. Moreover, a criminal will often break down cash proceeds into small amounts just below the reporting threshold.

Criminals also launder money by opening or purchasing businesses that tend to have a high turnover, such as restaurants, petrol stations, gaming companies and construction companies so that they can inject their illicit proceeds into the transactions of that business, including the purchase of the business itself.

Businesses that trade internationally are also often used as a medium of money laundering, with the value of goods imported or exported as well as any payments being misrepresented.

Cash also has the advantage of being easy to move across borders.

Yet despite all this, Malta is the most cash-intensive economy in the EU; it tops the list when it comes to both the amount of transactions conducted in cash in its economy as well as the value. This is the ideal setting for money laundering as well as tax evasion. Cash transaction limits are now common in most EU countries; in France, it is €1,000. Malta would do well to consider following suit.

Banks play an important role in money laundering. Former Europol director, Rob Wainwright, said in an interview with Politico last April that Europe’s work to curb money laundering is insufficient, as illegal cash is moving too easily through its banking system, and that: “Professional money launderers—and we have identified 400 at the top, top level in Europe—are running billions of illegal drug and other criminal profits through the banking system with a 99 percent success rate,”.

Pilatus Bank has captured the attention of the local and international media as well as that of the EU. So far, MFSA and the police have been unable to convert intelligence that had been provided by FIAU regarding its serious concerns on the bank’s operations into incriminating evidence, or ferret out any evidence of misconduct.

However the owner and chairman of the bank, Ali Sadr, is currently behind bars in a US prison awaiting trial for six charges that include fraud and money laundering that could see him receive a sentence of up to 125 years imprisonment. This raises serious questions on the due diligence conducted before granting Ali Sadr a license to operate a bank in Malta with a questionable business model, and whether there are any other Pilatus Banks among the other 24 licensed banks operating in Malta.

Money laundering needs to be taken seriously, and it is vital to identify it and act swiftly wherever and whenever it occurs to be successful in curbing crime. Governments must allocate an abundance of tools and resources to the institutions, agencies and forces of law and order involved in the battle against money laundering and there must be strong cooperation and collaboration between different countries on all levels.

Also, credit institutions, financial institutions, lawyers, notaries, accountants and other related professionals need to play their part in combatting money laundering by immediately reporting anything they come across in the course of their work which seems remotely or minimally suspicious.

Any efforts to fight crime, without a strong, resolute and relentless commitment to effectively combat money laundering will fail miserably.

This is the second instalment of a short series of explainers on Money Laundering, compiled with input from top local and international professionals in the field.